“I am to be your prisoner?”

He nods. “And I am to have your fortune. It is nothing between us, Margaret. Think of the safety of your son.”

“You will let me warn Henry of his danger?”

He rises to his feet. “Of course. You can write to him as you wish. But all your letters are to come through me, they will be carried by my men. I have to give the appearance of controlling you completely.”

“The appearance?” I repeat. “If I know you at all, you will give the appearance of being on both sides.”

He smiles in genuine amusement. “Always.”

WINTER 1483-84

It is a long, dark winter that I face, on my own at Woking. My ladies are taken from me, accused of plotting treason, and all of my trusted friends and messengers are turned away. I may not even see them. My household is chosen by my husband-my jailer-and they are men and women loyal only to him. They look at me askance, as a woman who has betrayed him and his interests, a faithless wife. I am living among strangers again, far from the center of court life, isolated from my friends, and far-so very far-from my defeated son. Sometimes I fear I will never see him again. Sometimes I fear that he will give up his great cause, settle in Brittany, marry an ordinary girl, become an ordinary young man-not a boy chosen by God for greatness and brought into the world by his mother’s agony. He is the son of a woman who was called to greatness by Joan of Arc herself. Can he become a sluggard? A drunkard? A boy who in the pothouses tells people that he might have been a king but for bad luck and a witch’s wind?

I find a way to send him one letter, before Christmas. It is not a letter of goodwill or Christmas cheer. The days are too dark for the exchange of gifts. It has been a bad year for the House of Lancaster. I have no joy to wish anyone. We have long, hard work to do if he is to reach his throne, and Christmas Day is the very day to start again.

My brother-in-law Jasper and my son Henry

I greet you well.

I understand that Elizabeth the false queen and Richard the usurper are talking together about her terms for release from sanctuary.

My wish is that my son Henry should publicly announce his betrothal to Princess Elizabeth of York. This should prevent any other marriage for her, remind her affinity and mine of his claim to the throne, demonstrate their previous support for him, and reestablish his claim to the throne of England.

He should do it on Christmas Day in Rennes Cathedral, just as Joan of Arc declared the King of France in Rheims Cathedral. This is my command as his mother and the head of his house.

Greetings of the season,

Margaret Stanley

I have time to meditate on the vanity of ambition and the sin of overthrowing an ordained king in the long winter nights of a miserable Christmas and a cheerless new year, as the impenetrable dark yields slowly to cold gray mornings. I go on my knees to my God and ask him why my son’s venture to gain his rightful place in the world was not blessed; why the rain was against him; why the wind blew his ships away; why the God of earthquake, wind, and fire could not calm the storm for Henry as He calmed it for Himself in Galilee? I ask Him that if Elizabeth Woodville, Dowager Queen of England, is a witch as everyone knows, then why should she come out of sanctuary and make an agreement with a usurping king? How can she get her way in the world when my own is blocked and mired? I stretch out on the cold tiles of the chancel steps and give myself up to holy and remorseful grief.

And then it comes to me. In the end, after many long nights of fasting and prayer, I hear an answer. I find that I know why. I come to an understanding.

At last I recognize that the sin of ambition and greed darkened our enterprise, our plans were overshadowed by a sinful woman’s desire for revenge. The plans were formed by a woman who thought herself the mother of a king, who could not be satisfied to be an ordinary woman. The fault of the enterprise lay in the vanity of a woman who would be a queen, and who would overturn the peace of the country for her own selfish desire. To know oneself is to know all, and I will confess my own sin and the part it played in our failure.

I am guilty of nothing more than a righteous ambition and a powerful desire to take my rightful place. It is a righteous rage. But Elizabeth Woodville is to blame for everything. She brought war to England for her own vanity and revenge; she it was who came to us filled with desire for her son, filled with pride in her house, puffed up with belief in her own beauty; and I should have refused to ally with her in her sinful ambition. It was Elizabeth’s desire for her son’s triumph that put us outside the pale of God’s patience. I should have seen her vanity and turned from it.

I have been much at fault, I see it all now, and I beg God to forgive me. My fault was to ally with Buckingham, whose vain ambition and ungodly lust for power brought down the rain on us, and with the Queen Elizabeth, whose vanity and desire were unsightly in the eyes of God. Also, who knows what she did to call up the rain?

I should have been, as Joan was, a woman riding out alone, with her own vision. By allying myself with sinners-and such sinners! A woman who was the widow of Sir John Grey. A boy who was married to Katherine Woodville.-I received the punishment for their sins. I was not sinful myself-and God who knows everything will know this-but I let myself join with them; and I, the godly, shared the punishment of sinners.

It is agony to me to think that their wrongdoing should destroy the righteousness of my cause; she a proclaimed witch, and the daughter of a witch, and he a peacock for all his short life. I should not have stooped to ally myself with them; I should have kept my own counsel and let them raise their own rebellion and do their own murders, and kept myself free of it all. But as it is, their failure has brought me down, their rain has washed away my hopes, their sin is blamed on me; and here I am, cruelly punished for their crimes.

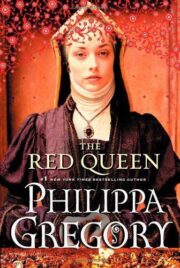

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.