Destroy what papers you have kept, and deny whatever you have done. Richard is coming to London, and there will be a scaffold built on Tower Green. If he believes half what he has heard, he will put you on it and I will be unable to save you.

Stanley

OCTOBER 1483

I have been on my knees all night, but I don’t know if God can hear me through the hellish noise of the rain. My son sets sail from Brittany with fifteen valuable ships and an army of five thousand men and loses them all in the storm at sea. Only two ships struggle ashore on the south coast, and they learn at once that Buckingham has been defeated by the rising of the river, his rebellion washed away by the waters, and Richard is waiting, dry-shod, to execute the survivors.

My son turns his back on the country that should have been his and sails for Brittany again, flying like a faintheart, leaving me here, unprotected, and clearly guilty of plotting his rebellion. We are parted once more, my heir and I, this time without even meeting, and this time it feels as if it is forever. He and Jasper leave me to face the king, who marches vengefully on London like an invading enemy, mad with anger. Dr. Lewis vanishes off to Wales; Bishop Morton takes the first ship that can sail after the storms and goes to France; Buckingham’s men slip from the city in silence and under lowering skies; the queen’s kin make their way to Brittany and to the tattered remains of my son’s makeshift court; and my husband arrives in London in the train of King Richard, whose handsome face is dark with the sullen rage of a traitor betrayed.

“He knows,” my husband says shortly as he comes to my room, his traveling cape still around his shoulders, his sympathy scant. “He knows you were working with the queen, and he will put you on trial. He has evidence from half a dozen witnesses. Rebels from Devon to East Anglia know your name and have letters from you.”

“Husband, surely he will not.”

“You are clearly guilty of treason, and that is punishable by death.”

“But if he thinks you are faithful-”

“I am faithful,” he corrects me. “It is not a matter of opinion but of fact. Not what the king thinks-but what he can see. When Buckingham rode out, while you were summoning your son to invade England, and paying rebels, while the queen was raising the southern counties, I was at his side, advising him, loaning him money, calling out my own affinity to defend him, faithful as any northerner. He trusts me now as he has never done before. My son raised an army for him.”

“Your son’s army was for me!” I interrupt.

“My son will deny that, I will deny that, we will call you a liar, and nobody can prove anything, either way.”

I pause. “Husband, you will intercede for me?”

He looks at me thoughtfully, as if the answer could be no. “Well, it is a consideration, Lady Margaret. My King Richard is bitter; he cannot believe that the Duke of Buckingham, his best friend, his only friend, should betray him. And you? He is astonished at your infidelity. You carried his wife’s train at her coronation, you were her friend, you welcomed her to London. He feels you have betrayed him. Unforgivably. He thinks you as faithless as your kinsman Buckingham, and Buckingham was executed on the spot.”

“Buckingham is dead?”

“They took off his head in Salisbury marketplace. The king would not even see him. He was too angry with him, and he is filled with hate towards you. You said that Queen Anne was welcome to her city, that she had been missed. You bowed the knee to him and wished him well. And then you sent out messages to every disaffected Lancastrian family in the country to tell them the cousins’ war had come again, and that this time you will win.”

I grit my teeth. “Should I run away? Should I go to Brittany too?”

“My dear, how ever would you get there?”

“I have my money chest; I have my guard. I could bribe a ship to take me. If I went down to the docks at London now, I could get away. Or Greenwich. Or I could ride to Dover or Southampton …”

He smiles at me and I remember they call him “the fox” for his ability to survive, to double back, to escape the hounds. “Yes, indeed, all that might have been possible; but I am sorry to tell you, I am nominated as your jailer, and I cannot let you escape me. King Richard has decided that all your lands and your wealth will be mine, signed over to me, despite our marriage contract. Everything you owned as a girl is mine, everything you owned as a Tudor is mine, everything you gained from your marriage to Stafford is now mine, everything you inherited from your mother is mine. My men are in your chambers now collecting your jewels, your papers, and your money chest. Your men are already under arrest, and your women are locked in their rooms. Your tenants and your affinity will learn you cannot summon them; they are all mine.”

I gasp. For a moment I cannot speak, I just look at him. “You have robbed me? You have taken this chance to betray me?”

“You are to live at the house at Woking, my house now; you are not to leave the grounds. You will be served by my people; your own servants will be turned away. You will see neither ladies-in-waiting, servants, nor your confessor. You will meet with no one and send no messages.”

I can hardly grasp the depth and breadth of his betrayal. He has taken everything from me. “It is you who betrayed me to Richard!” I fling at him. “You who betrayed the whole plot. It is you, with an eye to my fortune, who led me on to do this and now profit from my destruction. You told the Duke of Norfolk to go down to Guildford and suppress the rebellion in Hampshire. You told Richard to beware of the Duke of Buckingham. You told him that the queen was rising against him and I with her!”

He shakes his head. “No. I am not your enemy, Margaret; I have served you well as your husband. No one else could have saved you from the traitor’s death that you deserve. This is the best deal I could get for you. I have saved you from the Tower, from the scaffold. I have saved your lands from sequestration; he could have taken them outright. I have saved you to live in my house, as my wife, in safety. And I am still placed at the heart of things, where we can learn of his plans against your son. Richard will seek to have Tudor killed now; he will send spies with orders to murder Henry. You have signed your son’s death warrant with your failure. Only I can save him. You should be grateful to me.”

I cannot think, I cannot think through this mixture of threats and promises. “Henry?”

“Richard will not stop until he is dead. Only I can save him.”

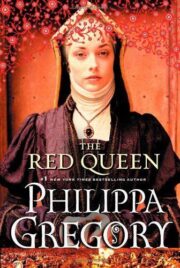

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.