What he doesn’t know yet is that a great shadow has fallen over his hopes and his security; what he does not know is that his greatest comrade and his first friend, the Duke of Buckingham, who put him on the throne, who swore fealty to him, who was to be bone of his bone and blood of his blood, another brother as trustworthy as those of the York affinity, is turned against him and has sworn to bring his destruction. Poor Richard, unknowing, innocent, celebrates in York, revels in the pride and love of his northern friends. What he does not know is that his greatest friend of all, the man he loves as a brother, has become indeed like a brother: as false to him as any envious rivalrous brother of York.

My husband, my lord Thomas Stanley, on a three-day leave from his duties at Richard’s court at York, comes to me in the evening, in the hour before dinner, and waves my women from the room, without a word of courtesy to them or to me. I raise an eyebrow at his rudeness and wait.

“I have no time for anything but this question,” he snaps. “The king has sent me on this private errand, though God knows he shows little sign of trusting me. I have to be back with him the day after tomorrow, and he eyes me as if he would have me under arrest again. He knows there is a rebellion in the making; he suspects you and therefore me too, but he doesn’t know whom he can trust. Tell me this one thing: Have you ordered the deaths of the princes? And is it done?”

I glance at the closed door and rise to my feet. “Husband, why do you ask?”

“Because my land agent today asked me were they dead. My chief of horse asked me had I heard the news. And my vintner told me that half the country believe it is so. Half the country think they are dead, and most of them think that Richard did it.”

I conceal my pleasure. “But really, how would I do such a thing?”

He puts his clenched fist under my face and snaps his fingers. “Wake up,” he says rudely. “You are talking to me, not to one of your acolytes. You have dozens of spies, a massive fortune at your own command, and now the Duke of Buckingham’s men to call on, as well as your own guard. If you want it done, it can be done. So is it done? Is it over?”

“Yes,” I say quietly. “It is done. It is over. The boys are dead.”

He is silent for a moment, almost as if he were saying a prayer for their little souls. Then he asks: “Have you seen the bodies?”

I am shocked. “No, of course not.”

“Then how do you know they are dead?”

I draw very close to him. “The duke and I agreed it should be done, and his man came to me late one night and told me that the deed was done.”

“How did they do it?”

I cannot meet his eyes. “He said that he and a couple of others caught them sleeping and pressed them in their bed, smothered them with the mattresses.”

“Only three men!”

“Three,” I say defensively. “I suppose it would need three-” I break off as I see that he is imagining, as I am, holding a ten-year-old boy and his twelve-year-old brother facedown in their beds and then crushing them with a mattress. “Buckingham’s men,” I remind him. “Not mine.”

“Your orders, and three witnesses to it. Where are the bodies?”

“Hidden under a stair in the Tower. When Henry is proclaimed king, he can discover them there and declare the boys were killed by Richard. He can hold a Mass, a funeral.”

“And how do you know that Buckingham has not played you false? How do you know that he has not spirited them away and they are still alive somewhere?”

I hesitate. Suddenly I feel that I may have made a mistake, giving dirty work to others to do. But I wanted it to be Buckingham’s men, and all the blame on Buckingham. “Why would he do that? It is in his interest that they should be dead,” I say, “just as much as ours. You yourself said that. And if the worst comes to the worst, and he has tricked me, and they are alive in the Tower, then someone can kill them later.”

“You put a lot of faith in your allies,” my husband says unpleasantly. “And you keep your hands clean. But if you don’t strike the blow, you don’t know if it goes home. I just hope that you have done the job. Your son will never be safe on the throne if there is a York prince somewhere in hiding. He will spend his life looking over his shoulder. There will be a rival king waiting in Brittany for him, just as he was there for Edward. Just as he terrorizes Richard. Your precious son will be haunted by fear of a rival, just as he haunts Richard. Tudor will never have a moment’s peace. If you have botched this, you have given your son over to be dogged by an unquiet spirit, and the crown will never sit securely on his head.”

“I do the will of God,” I say fiercely. “And it has been done. And I won’t be questioned. Henry will be safe on his true throne. He will not be haunted. The princes are dead, and I am guilty of nothing. Buckingham did it.”

“At your suggestion.”

“Buckingham did it.”

“And you are sure they were both killed?”

I hesitate for a moment as I think of Elizabeth Woodville’s odd words: “It’s not Richard.” What if she put a changeling in the Tower for me to kill? “Both of them,” I say steadily.

My husband smiles his coldest smile. “I shall be glad to be sure of it.”

“When my son comes into London in triumph and finds the bodies, lays the blame on Buckingham or Richard, and gives them a holy burial, you will see that I have done my part.”

I go to bed uneasy, and the very next day, straight after matins, Dr. Lewis comes to my rooms looking strained and anxious. At once I say I am feeling unwell and send all my women away. We are alone in my privy chamber, and I let him take a stool and sit opposite me, almost as an equal.

“The Queen Elizabeth summoned me to sanctuary last night, and she was distraught,” he says quietly.

“She was?”

“She had been told that the princes were dead, and she was begging me to tell her that it was not the case.”

“What did you say?”

“I didn’t know what you would have me say. So I told her what everyone in the city is saying: that they are dead. That Richard had them killed either on the day of his coronation, or as he left London.”

“And she?”

“She was deeply shocked; she could not believe it. But Lady Margaret, she said a terrible thing-” He breaks off, as if he dare not name it.

“Go on,” I say but I can feel a cold shiver of dread creeping up my spine. I fear I have been betrayed. I fear that this has gone wrong.

“She cried out at first and then she said: ‘At least Richard is safe.’”

“She meant Prince Richard? The younger boy?”

“The one they took into the Tower to keep his brother company.”

“I know that! But what did she mean?”

“That’s what I asked her. I asked her at once what she meant, and she smiled at me in the most frightening way and said: ‘Doctor, if you had only two precious, rare jewels and you feared thieves, would you put your two treasures in the same box?’”

He nods at my aghast expression.

“What does she mean?” I repeat.

“She wouldn’t say more. I asked her if Prince Richard was not in the Tower when the two boys were killed. She just said that I was to ask you to put your own guards into the Tower to keep her son safe. She would say nothing more. She sent me away.”

I rise from my stool. This damned woman, this witch, has been in my light ever since I was a girl, and now, at this very moment when I am using her, using her own adoring family and loyal supporters to wrench the throne from her, to destroy her sons, she may yet win, she may have done something that will spoil everything for me. How does she always do it? How is it that when she is brought so low that I can even bring myself to pray for her, she manages to turn her fortunes around? It must be witchcraft; it can only be witchcraft. Her happiness and her success have haunted my life. I know her to be in league with the devil, for sure. I wish he would take her to hell.

“You will have to go back to her,” I say, turning to him.

He almost looks as if he would refuse.

“What?” I snap.

“Lady Margaret, I swear, I dread going to her. She is like a witch imprisoned in the cleft of a pine tree; she is like an entrapped spirit; she is like a water goddess on a frozen lake, waiting for spring. She lives in the gloom of sanctuary with the river flowing all the time beside their rooms, and she listens to the babble as a counsellor. She knows things that she cannot know by earthly means. She fills me with terror. And her daughter is as bad.”

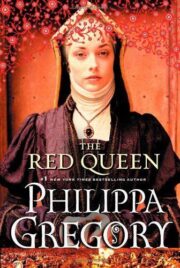

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.