Yes, I think. And you too think that you have secured me, and that I will bring in my son to kill Richard for you. That I will use my precious Henry as a weapon for such a one as you, to give you a safe passage to the throne.

“And if,” he looks pained, “if, God forbid, your son Henry was to fall in battle?”

“Then you would be king,” I say. “I have only one son, and he is the only heir to my house. No one could deny that if Henry were dead, then your claim to the throne would be supreme. And if he lives, then you would have his gratitude and whatever lands you wanted to command. Certainly, I can promise for him that all the Bohun lands would be restored to you. The two of you would have brought peace at last to England and rid the country of a tyrant. Henry would be king, and you would be the greatest duke. And if he died without issue, you would be his heir.”

He slips from his stool and kneels to me, holds his hands up to me in the old gesture of fealty. I smile down at him, this beautiful young man, as handsome as a player in a masque, mouthing words that surely no one could believe, offering loyalty where he seeks only his own good. “Will you take my fealty for your son?” he asks, his eyes shining. “Will you accept my oath and swear that he will join with me against Richard? Us two together?”

I take his hands in my cool clasp. “On behalf of my son, Henry Tudor, the rightful King of England, I accept your fealty,” I say solemnly. “And you, and he, and Elizabeth the dowager queen together will overthrow the Boar and bring joy back to England once more.”

I ride away from Buckingham’s dinner feeling oddly unhappy, not at all as a woman in triumph. I should feel exultant: he thinks he has trapped my son into arming and fighting for his rebellion, and actually, we have ensnared him. The task I set myself is accomplished; God’s will is done. And yet … and yet … I suppose it is the thought of those two boys in the Tower, saying their prayers and climbing into their big bed, hoping that tomorrow they will see their mother, trusting that their uncle will release them, not knowing that there is a powerful alliance now of myself, my son, and the Duke of Buckingham who wait to hear of their deaths, and will not wait for much longer.

SEPTEMBER 1483

At last I have come into my own. I have inherited the kingdom I dreamed of when I prayed to Joan the Maid and wanted to be her, the only girl to see that her kingdom should rise, the only woman to know, from God Himself, what should be done. My rooms in our London house are my secret headquarters of rebellion; every day messengers come and go with news of arming, asking for money, collecting their weapons and smuggling them secretly out of the city. My table of work, which was once piled with books of devotion for my studies, is now covered with carefully copied maps, and hidden in its drawers are codes for secret messages. My ladies approach their husbands, their brothers, or their fathers, swear them to secrecy, and bind them to our cause. My friends in the church and in the city and on my lands link one to another and reach out to the country in a web of conspiracy. I judge who shall be trusted and who shall not, and I approach them myself. Three times a day I go down on my knees to pray, and my God is the God of righteous battles.

Dr. Lewis goes between me and the Queen Elizabeth almost daily, as she in her turn draws out those still loyal to the York princes, the great men and loyal servants of the old royal household, and her brothers and her son are everywhere in secret in the counties around London calling out the York affinity, while I summon those who will fight for Lancaster. My steward Reginald Bray goes everywhere, and my beloved friend John Morton as house guest and prisoner is in daily contact with Henry Stafford, the Duke of Buckingham. He tells the duke of our recruiting and reports back to me that the thousands of men that Buckingham can command are secretly arming. To my own people, I give the assurance that Henry will marry the Princess Elizabeth of York, and unite the country with his victory. This brings them out for me. But the Yorks and the common people care nothing for my Henry; they are anxious only to set the princes free. They are desperate for the freedom of their boys, they are united against Richard, they would join with any ally-the devil himself-as long as they can free the York boys.

The Duke of Buckingham seems to be true to my plan, though I don’t doubt he has one of his own, and promises he will gather up his men and Tudor loyalists through the marches of Wales, cross the Severn, and enter England from the west. At the same time my son is to land in the south and march his forces north. The queen’s men will come out of all the southern counties, where her strength lies, and Richard, still in the north, will have to scramble for recruits as he marches south to greet not one but three armies and choose the place of his death.

Jasper and Henry raise their troops from the prisons and streets of the worst cities in northern Europe. They will be paid fighters and desperate prisoners who are released only to go to war under the Tudor banner. We don’t expect them to stand against more than one charge, and they will have no loyalty and no sense of a true cause. But their numbers alone will take the battle. Jasper has raised five thousand of them, truly five thousand, and is drilling them into a force that would strike terror into any country.

Richard, ignorant, far away in York, delighting in the loyalty of that city for their favorite son, has no idea of the plans that we are forming in the very heart of his own capital, but he is astute enough to know that Henry poses a danger. He is trying to persuade King Louis of France into an alliance that would include the handing over of my boy. He is hoping to make a truce with Scotland; he knows that my Henry will be collecting troops; he knows of the betrothal, and that my son is in alliance with the Queen Elizabeth, and he knows that they will either come on the autumn winds this year, or wait for spring. He knows this, and he must fear it. He doesn’t know where I stand in this; whether I am the loyal wife of a loyal retainer whom he has bought with fees and positions, or whether I am the mother of a son with a claim to the throne. He must watch, he must wait, he must be filled with wondering.

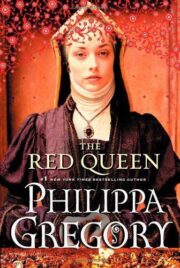

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.