There is a rap on the door, and my lord’s guards admit the steward of the abbey. “Dinner is served, my lady, my lord.”

“God bless you, my husband,” I say formally. “I learn so much from studying you.”

“And you,” he says. “And God bless your meeting with His Grace the duke; may much good come of it.”

I can hear the Duke of Buckingham approaching along the winding dirt road even before I can see him. He rides with a train as great as a king’s, with outriders going ahead and blowing trumpets to warn everyone to clear the highway for the great duke. Even when there is no one as far as the eye can see, but only a little boy herding sheep under a tree and a small village in the distance, the trumpeters sound the call and the horses, more than a hundred of them, thunder along behind, raising a plume of dust on the summer road that blows like a cloud behind the rippling banners.

The duke is at the forefront of the riders, on a big bay warhorse, caparisoned with a saddle of red leather trimmed with golden nails, his personal standard before him, and three men-at-arms riding around him. He is dressed for hunting, but his boots, also red leather, are so fine that a lesser man would have kept them for dancing. His cloak, thrown back over his shoulders, is pinned with a great golden brooch; his hat badge is of gold and rubies. There is a fortune in jewels embroidered on his jerkin and his waistcoat; his breeches are of the most smooth tan broadcloth, trimmed with red leather laces. He was a vain, furious boy when Elizabeth Woodville took him as her ward and humiliated him by marrying him to her sister, and now he is a vain, furious man, not yet thirty years old, taking his revenge on a world that has never, in his mind, shown him enough respect.

I first met him when I married Henry Stafford, and then he was a little boy, spoiled by the indulgent duke, his grandfather. The death of his father and then that of his grandfather gave him the dukedom while he was still a child and taught him to think of himself as born great. Three of his grandparents are descended from Edward III, and so he believes himself to be more royal than the royal family. Now, he considers himself the Lancaster heir. He would consider his claim is greater than that of my son.

He pretends surprise at suddenly seeing my more modest train, though it must be said, I always travel with fifty good men-at-arms, and my own standard and the Stanley colors go before me. He raises his hand to halt his troop. We approach each other slowly, as if to parley, and his young charming smile beams out at me like a sun rising. “Well met, my lady cousin!” he cries out, and all his troop’s banners dip in respect. “I didn’t think to see you so far from your home!”

“I have to go to my house at Bridgnorth,” I say clearly for any spies who might be listening. “And I had thought you were with the king?”

“I am returning to him now from my house at Brecon,” Buckingham says. “But do you want to break your journey? There is Tenbury just ahead of us. Would you do me the honor of dining with me?” He casts a casual wave towards his troop. “I have my kitchen servants with me, and provisions. We could have dinner together.”

“I should be honored,” I say quietly, and I turn my horse and ride beside him as my outnumbered guard stand aside and then follow the Buckingham troops to Tenbury.

The little inn has a small room with a table and a few stools, adequate for our purpose, and the men rest their horses in lines in the nearby field and light their own campfires to roast their meats. Buckingham’s cook takes over the meager kitchen of the inn, and soon has servants running backwards and forwards to kill a couple of chickens and fetch his ingredients from the wagon. Buckingham’s steward brings us two glasses of wine from the cellar wagon and serves them in the duke’s own glassware, with his seal engraved at the rim. I note all his worldly extravagance and folly and think, This is a young man who thinks he is going to play me.

I wait. The God I serve is a patient God, and He has taught me that sometimes the best thing to do is to wait and see what comes. Buckingham has always been an impatient boy, and he can hardly pause for the door to be closed behind his steward before he starts.

“Richard is unbearable. I meant only that he should protect us against the ambition of the Riverses, and I warned him against them for that reason; but he has gone too far now. He has to be pulled down.”

“He is king now,” I observe. “You warned him early and served him so well that he has become the tyrant that you feared the Riverses would be. And my husband and I myself are sworn to serve him, as are you.”

He waves his hand and spills a little wine. “An oath of fealty to a usurper is no oath at all,” he says. “He is not the rightful king.”

“Who is, then?”

“Prince Edward, I suppose,” he says quickly, as if that is not the only question of importance. “Lady Stanley, you are older and wiser than me, I have trusted your holy judgment for all of my life. Surely, you feel that we must free the princes from the Tower and restore them to their state? You were such a loving lady to the Queen Elizabeth. Surely, you feel that her boys must be freed, and Prince Edward must take his father’s throne?”

“Surely,” I say. “If he were a legitimate son. But Richard says he is not; you yourself proclaimed him a bastard, and his father a bastard before him.”

Buckingham looks troubled by this, as if it were not he who swore to everyone that Edward had been married before he promised marriage to Elizabeth. “Indeed, I fear that much is true.”

“And if you put the so-called prince on the throne, you would stand to lose all the wealth and positions you have been given by Richard.”

He waves away the post of High Steward of England as if it were not the greatest honor in the land. “The gifts of a usurper are not what I want for my house,” he says grandly.

“And I would gain nothing at all,” I remark. “I would still be lady-in-waiting to the queen. I would return to the service of the Dowager Queen Elizabeth, having served the Queen Anne-so I would be still in service. And you would have risked everything to restore the Rivers family to power. And we know what a grasping, numerous family they are. Your wife, the queen’s sister, would rule you once more. She will repay you for keeping her at home in disgrace. They will all laugh at you again, as they did when you were a little boy.”

His hatred for them flares in his eyes, and he quickly glances away at the fireplace, where a little fire licks at the logs. “She does not dominate me,” he says, irritated. “Whatever her sister is. Nobody laughs at me.”

He waits; he hardly dares to tell me what he truly wants. The servant comes in with some little pies, and we take them with our wine, thoughtfully, as if we had met together to dine and were savoring the meal.

“I do fear for the lives of the princes,” I say. “Since the attempt to free them came so close, I cannot help but think that Richard may send them far away, or worse. Surely, he cannot tolerate the risk of them staying in London, a center for every plot? Everyone must think that Richard will destroy them. Perhaps he will take them to his lands in the north and they will not survive it. Prince Richard has a weak chest, I fear.”

“If he were, God forbid, to kill them in secret, then the Rivers line would be over, and we would be free of them,” the duke says, as if this has occurred to him now, for the first time.

I nod. “And then, any rebellion that destroyed Richard would leave the throne open for a new king.”

He raises his face from the glow of the fire and looks at me with a bright, open hopefulness. “Do you mean your son, Henry Tudor? Do you think of him, my lady? Would he take up the challenge and restore Lancaster to the throne of England?”

I don’t hesitate for a moment. “We have done badly enough with York. Henry is the direct Lancaster heir. And he has waited for his chance to return to his country and claim his birthright for all his life.”

“Does he have arms?”

“He can raise thousands,” I promise. “The Duke of Brittany has promised his support-he has more than a dozen ships, more than four thousand men, an army at his command. His name alone can turn out Wales, and his uncle Jasper would be his commander. If you and he were to unite to fight against Richard, I think you would be unbeatable. And if the dowager queen were to summon her affinity, thinking she was fighting for her sons, we could not fail.”

“But when she found out that her sons were dead?”

“As long as she found it out after the battle, it would make no difference to us.”

He nods. “And then she would just retire.”

“My son Henry is betrothed to marry the Princess Elizabeth,” I remark. “Elizabeth Woodville would still be mother of the queen; that would be enough for her, if her sons were gone.”

He beams as he suddenly understands my plan. “And she thinks she has secured you!” he exclaims. “That your ambitions are one with hers.”

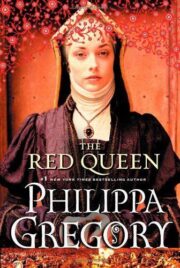

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.