In the early hours of the morning, when the sky is just getting gray, there is a scratch on the door that makes my heart thud, and I hurry to open it. The captain of the guard is outside, his black jerkin torn, a dark bruise on the side of his face. I let him in without a word and pour him a glass of small ale. I gesture that he may sit at the fireside, but I remain standing behind my chair, my hands clenched on the carved wood to stop them trembling. I am as frightened as a child at what I have done.

“We failed,” he says gruffly. “The boys were better guarded than we thought. The man who should have let us in was cut down while he was fumbling with the bolt. We heard him scream. So we had to ram the door, and while we were trying to lift it from its hinges, the Tower guards came out from the courtyard behind us, and we had to turn and fight. We were trapped between the Tower and the guards and had to fight our way out. We didn’t even get into the White Tower. I could hear the doors slamming inside and shouting as the princes were taken deeper into the Tower. Once the alarm was sounded there was no chance we would get to them.”

“Were they forewarned? Did the king know there would be an attack?” And if so, does the king know who is in the plot, I think. Will the boar turn on us again?

“No, it wasn’t an ambush. They got the guard out quickly, and they got the door shut, and the queen’s spy inside couldn’t get it open. But at first, we caught them unawares. I am sorry, my lady.”

“Any captured?”

“We got all our men away. There was one injured of ours; they’re seeing to him now, a flesh wound only. And there was a couple of York men down. But I left them where they fell.”

“The Yorks were there, all of them?”

“I saw the queen’s brother Richard was there, and her brother Lionel, her son Thomas who was said to be missing, and they had a good guard, well armed. I think there were Buckingham men among them too. They were there in strength, and they put up a good fight. But the Tower was built by the Normans to hold against London. You can hold it against an army for half a year, once you get the door shut. Once we lost the surprise we were beaten.”

“And nobody knew you?”

“We all said we were Yorks, we wore white roses, and I am sure we passed as that.”

I go to my box, heft a purse in my hand, and give it to the captain. “Spread this around the men, and ensure that they don’t speak of tonight, even among themselves. It would cost them their lives. It was treason, since it failed. It would be death to a man who boasted he had been there. And no order came from my husband or from me.”

The captain rises. “Yes, my lady.”

“Did the queen’s kin all get safely away?”

“Yes. But her brother swore that they would come again. He shouted aloud so that the boys could hear, that they must be brave and wait, for he would raise the whole of England to free them.”

“Did he? Well, you have done your best-you can go.”

The young man bows and goes from the room.

I go on my knees before the fire. “Our Lady, if it is Your will that the York boys be spared, then send me, Your servant, a sign. Their safety tonight cannot be a sign. Surely, it cannot be Your will that they live? It cannot be Your will that they inherit? I am Your obedient daughter in every way, but I cannot believe that You would have them on the throne rather than the true Lancaster heir, my son Henry.”

I wait. I wait for a long time. There is no sign. I take it to heart that there is no sign, and so the York boys should not be spared.

I leave London the next day. It suits me not to be seen in the city while they are doubling the guard and asking who attacked the Tower. I decide to take a visit to the cathedral of Worcester. It has long been my wish to visit; it is a Benedictine cathedral, a center of learning. Elizabeth the queen sends a message that is brought to me as we are saddling up, to say that her kinsmen have gone to ground in London and the countryside nearby, and that they are organizing an uprising. I reply to pledge my support and tell her that I am on my way to the Duke of Buckingham to recruit him and his whole affinity to our side in open rebellion.

It is hot weather for traveling, but the roads are dry and we make good time. My husband rides back from the court at Worcester to meet me for a night on the road. The new King Richard, happy and confident, greeted with enthusiasm everywhere he goes, grants Lord Stanley leave of absence for a night, assuming that we want to be together as husband and wife. But my lord is anything but loving when he comes into the guest rooms in the abbey.

He spares no time on gentle greetings. “So they botched it,” he says.

“Your captain tells me it could hardly be done. But he said the Tower wasn’t forewarned.”

“No, the king was appalled; it was a shock to him. He had heard of my brother’s letter of warning, and that will do us some good. But the princes are to be taken to inner rooms, more easily guarded than the royal rooms, and not allowed out again until he returns to London. Then he will take them away from London. He is going to set up a court for the young royal cousins. The Duke of Clarence’s children, his own son, all the York children, will be kept in the north at Sheriff Hutton, and held there, far from any lands where Elizabeth Woodville has any influence. She’ll never rescue them from Neville lands, and he will probably marry her to a northern lord who will take her away too.”

“Might he have someone poison them?” I ask. “To get them out of the way?”

My husband shakes his head. “He has declared them illegitimate, and so they cannot inherit the throne. His own son is going to be invested as Prince of Wales as soon as we get to York. The Riverses are defeated; he just wants to make sure they are not the figurehead of a forlorn hope. Besides, they would be worse for him as dead martyrs than they are as feeble claimants. The ones he really wants dead are the Rivers tribe: the Woodvilles and all their kin, who would rally behind the princes. But the best of them is dead, and the rest will be hunted down. All the country accepts Richard as king and the true York heir. You would have to see it to believe it, Margaret, but every city we go through pours out to celebrate his coronation. Everyone would rather have a strong usurper on the throne than a weak boy; everyone would rather have the king’s brother than go through the wars again for a king’s son. And he promises to be a good king-he is the picture of his father, he is a York, and beloved.”

“And yet there are many who would rise against him. I should know, I am mustering them.”

He shrugs. “Yes-you would know better than I. But everywhere we have been, I have seen the people welcome King Richard as the great heir and loyal brother of a great king.”

“The Riverses could yet defeat him. The queen’s brothers and her Grey son have secured the support of Kent and Sussex; Hampshire is theirs. Every man who ever served in the royal household would turn out for them. There is always support for my house in Cornwall, and the Tudor name will bring out Wales. Buckingham has tremendous lands and thousands of tenants, and my son Henry is promised an army of five thousand from the Duke of Brittany.”

He nods. “It could be done. But only if you can be certain of Buckingham. You are not strong enough without him.”

“Morton says that he has completely turned Buckingham against Richard. My steward Reginald Bray has spoken with them both. I will know more when I see him.”

“Where are you meeting?”

“By chance, on the road.”

“He will play you,” my husband warns me. “As he has played Richard. The poor fool Richard even now thinks that Buckingham loves him as a brother. But it turns out that it is always his own ambition at the end of it. He will agree to support your son’s claim to the throne, but think to let Tudor do the fighting for him. He will hope that Tudor and the queen will defeat Richard and leave the way open for him.”

“It is lip service for all of us. We are all fighting only for our own cause, all of us promising our loyalty to the princes.”

“Yes, only the boys are quite innocent,” he remarks. “And Buckingham will be planning their deaths. No one in England would support his claim if they were still alive. And of course, as High Steward of England, with the Tower in his command, he is better placed than any of us to see them murdered. His servants are inside already.”

I pause as his meaning becomes clear to me. “You think he would do it?”

“In a moment.” He smiles. “And when he does it, he could give the orders in the name of the king. It could be made to look like the orders of Richard. He himself would make it look like Richard’s doing.”

“Is he planning this?”

“I don’t know if he has even thought of it yet. Certainly, someone should make sure it has occurred to him. For sure, someone who wanted the boys dead could do the deed no better way than to make it Buckingham’s task.”

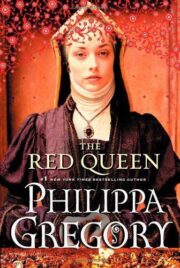

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.