In the morning, my husband meets me at breakfast. “I am summoned to attend a Privy Council meeting,” he says, showing me a warrant with the seal of the boar. Neither of us looks directly at it; the letter sits on the table between us like a dagger. “And you are to go to the royal wardrobe and prepare the coronation robes for Anne Neville. The robes for a queen. You are to be lady-in-waiting to Queen Anne. We are released from house arrest without a word. And we are in royal service again, without a word spoken.”

I nod. I will undertake the work for King Richard that I was doing for King Edward. We will wear the same gowns, but the gown of gold and ermine that was ready for the Dowager Queen Elizabeth will be cut down for her sister-in-law, the new Queen Anne.

My ladies-in-waiting and the Stanley men-at-arms are seated all around us, so my husband and I exchange no more than a small glance of triumph at our own survival. This will be the third royal house that I have served, and each time I have bowed low and thought of my own son as heir. “I shall be honored to serve Queen Anne,” I say smoothly.

It is my destiny to smile at the changes of the world and await my reward in heaven, but even I balk for a moment at the doorway of the queen’s chambers when I see little Anne Neville-daughter of the Kingmaker Warwick, born well enough, royally married, widowed to nothing, and now risen again to the throne of England itself-standing by the great fireplace in her traveling cloak surrounded by her ladies from the north, like a gypsy encampment from the moors. They see me in the doorway; the steward of her chamber bellows, “Lady Margaret Stanley!” in an accent no one living south of Hull could understand, the women shuffle aside, so that I can walk towards her, and I step in and go down to my knees, abase myself to yet another usurper, and hold up my hands in the gesture of fealty.

“Your Grace,” I say to the woman who was picked up from disgrace and poverty by the young Duke Richard because he knew he could claim the Warwick fortune with this most unlucky bride. Now she is to be Queen of England, and I have to kneel to her. “I am so glad to offer you my service.”

She smiles at me. She is pale as marble, her lips pale, her eyelids the palest pink. Certainly, she cannot be well; she puts her hand on the stone of the fireplace and leans against it as if she is weary.

“I thank you for your service, and I would have you serve as my senior lady-in-waiting,” she says quietly, a little catch in her breath. “You will carry my train at my coronation.”

I bow my head to hide my flare of joy. This is to honor my family; this is to have the House of Lancaster one pace from the crown as it is held over an anointed head. I will be just one step behind the Queen of England and-God knows-ready to step up. “I am glad to accept,” I say.

“My husband speaks so highly of the wisdom of Lord Thomas Stanley,” she says.

So highly that the pikemen nearly sliced off his head and held him for a week under house arrest. “We have long been in service to the House of York,” I remark. “You and the Duke have been sadly missed while you were away from court in the north. I am glad to welcome you home to your capital city.”

She makes a little gesture with her hand and her page brings a stool over so that she can sit before the fire. I stand before her and I watch her shoulders shake as she coughs. This is a woman who is not going to make old bones. This is a woman who is not going to conceive a quiver of heirs for York, not like the fecund Queen Elizabeth. This is a woman who is sick and weak. I doubt she will last five more years. And then? And then?

“And your son, Prince Edward?” I inquire demurely. “Is he coming to the coronation? Should I order your chamberlain to prepare rooms for him?”

She shakes her head. “His Grace is not well,” she says. “He will stay in the north for now.”

Not well? I think to myself. Not well enough to come to the coronation of his own father, is not well at all. He was always a pale boy with his mother’s slight build, seldom seen around court; they always kept him away from London for fear of the plague. Has he, perhaps, not outgrown childhood weakness but is going from a frail boy to a sickly adult? Has Duke Richard failed to get himself an heir who will outlive him? Is there now only one strong heartbeat between my son and the throne?

SUNDAY, JULY 6, 1483

We are where we planned to be, one step from the crown. My husband follows the king, with the mace of the Constable of England in his grasp; I follow the new Queen Anne, holding her train. Behind me comes the Duchess of Suffolk, the Duchess of Norfolk behind her. But it is I who walk in the footsteps of the queen, and when she is anointed with holy oil, I am close enough to smell the heady musk of it.

They have spared no cost for this ceremony. The king is dressed in a gown of purple velvet, a canopy of cloth of gold carried over his head. My kinsman Henry Stafford, the young Duke of Buckingham, is in blue with a cartwheel emblem of solid gold thread dazzling on his cloak. He holds the king’s train in one hand; in the other he has the staff of the High Steward of England, his reward for supporting and guiding Duke Richard to the throne. The place for his wife, Katherine Woodville, the dowager queen’s sister, is empty. The duchess has not come to celebrate the usurping of her family’s throne. She is not with her treasonous husband. He hates her for her family, for her triumph over him when he was young and she was the king’s sister-in-law. This is just the first of many times that she can expect humiliation in future.

I walk behind the queen all the day. When she goes in to dine in Westminster Hall, I sit at the table for the ladies as she is served the magnificent dinner. The king’s champion himself bows to our table and to me, after he has bellowed his challenge for King Richard. It is a dinner as grand and as self-important as any one of the great occasions of Edward’s court. The dining and the dancing go on till midnight, and after. Stanley and I leave in the early hours of the morning, and our barge takes us upriver to our house. As I sit myself in the rear of the barge, my furs gathered around me, I see a small light shining low from a waterside window beneath the dark bulk of the abbey. I know for a certainty it is Queen Elizabeth, queen no more, named as a whore and not even recognized as a widow, her candle shining over the dark waters, listening to her enemy’s triumph. I think of her watching me go by in my beautiful barge, rowing away from the king’s court, as years ago she watched me row my son towards the king’s court. She was in sanctuary then too.

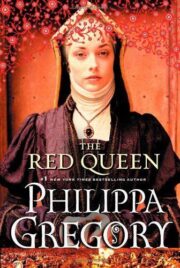

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.