I think it is almost a part of my prayer when I hear the march of many feet down the street and the clanking on the cobbles as a hundred pikemen ground their pikes, and then there is a hammering on the big street door of our London house.

I am halfway down the stairs as the porter’s boy comes running up to tell the maids to call me. I grab him by the arm. “Who is it?”

“Duke Richard’s men,” he gabbles. “In his livery, with the master, they’ve got the lord, your husband. Smacked in the face, blood on his jerkin, bleeding like a pig …”

I push him to one side as he is making no sense, and I run down to the cobbled entrance where the gatemen are swinging open the gate and Duke Richard’s troop march in, and at the center of them is my husband, swaying on his feet, blood pouring from a wound to his head. He looks at me, and his face is white and his eyes are blank with shock.

“Lady Margaret Stanley?” asks the commander of the guard.

I can hardly drag my eyes from the symbol of the boar on his livery. A tusked boar just as my husband dreamed was coming for him.

“I am Lady Margaret,” I say.

“Your husband is under house arrest, and he and you cannot leave here. There will be guards stationed at all doorways and in your house, and at the doors and windows of his chambers. Your household and necessary servants can go about their business, but they will be stopped and searched at my command. Do you understand?”

“Yes,” I whisper.

“I am going to search the house for letters and papers,” he says. “Do you understand this too?”

There is nothing in my rooms that would incriminate either of us. I burn anything dangerous as soon as I have read it, and I never keep a copy of my own letters. All my work for Henry is between God and me.

“I understand. May I take my husband to my closet? He is wounded.”

He gives a grim smile. “When we marched in to arrest Lord Hastings, your husband dived under the table and nearly took off his own head on a pike blade. It looks worse than it is.”

“You arrested Lord Hastings?” I ask incredulously. “On what charge?”

“Madam, we have beheaded him,” he says shortly. He pushes past me into my own rooms, and his men fan out in my yard and take up their positions, and we are prisoners in our own great house.

Stanley and I go to my closet, surrounded by pikemen, and only when they have seen that the window is too small for escape do they step back and close the door on the two of us and we are alone.

Stanley throws his bloodstained jerkin and spoiled shirt to the floor with a shudder, and he sits on a stool, stripped to the waist. I pour a jug of water into the ewer and start to wash the cut. It is shallow and long, a glancing blow, not one aimed to kill, but an inch lower and he would have lost an eye. “What is happening?” I whisper.

“Richard came in at the start of the meeting to determine the order of the coronation, all smiles, asked Bishop Morton to send out for strawberries from his garden, very affable. We started our work on the coronation, the seating, the precedence, the usual things. He went out again, and while he was outside, someone must have brought him some news or a message, and he came in a changed man, with a face dark with rage. The troop came in after him like they were overrunning a fort, banging in the door, weapons at the ready. They swung at me, I dropped down, Morton leaped back, Rotherham ducked behind his chair; they took Hastings before he could defend himself.”

“But why? What had been said?”

“Nothing! Nothing had been said. It was as if Richard just unleashed his power. They just grabbed Hastings and took him.”

“Took him where? On what charge? What did they say?”

“They said nothing. You don’t understand. It wasn’t an arrest. It was a raid. Richard was shouting like a madman that he was under an enchantment, that his arm was failing him, that Hastings and the queen were destroying him by witchcraft-”

“What?”

“He pulled up his sleeve and showed us his arm. His sword arm-you know how strong his right arm is. He says it is failing him, he says it is shriveling away.”

“Dear God, has he run mad?” I pause in wiping the blood; I cannot believe what I am hearing.

“They dragged Hastings out. Not another word. They pulled him outside though he was kicking and swearing and digging in his heels. There was some old lumber lying around from the building work, and they just threw down a piece of timber, forced him down on it, and took his head off with one swing.”

“A priest?”

“There was no priest. Do you not hear what I am saying? It was a kidnap and a murder. He had no time even to say his prayers.” Stanley starts to shake. “Dear God, I thought they were coming after me. I thought I would be next. It was like the dream. The smell of blood and nobody there to save me.”

“They beheaded him before the Tower?”

“As I said, as I said.”

“So if the prince looked out of his window, hearing the noise, he will have seen his father’s dearest friend beheaded on a log? The man he called his uncle William?”

Stanley is silent, looking at me. A trickle of blood runs down his face and he smears it with the back of his hand, turning his cheek red. “Nobody could have stopped them.”

“The prince will see Richard as his enemy,” I say. “He can’t call him lord protector after this. He will think him a monster.”

Stanley shakes his head.

“What is going to happen to us?”

His teeth are starting to chatter. I put down the bowl and wrap a blanket around his shoulders.

“God knows, God knows. We are under house arrest for treason; they suspect us of plotting with the queen and Hastings. Your friend Morton too, and they took Rotherham as well. I don’t know how many others. I suppose Richard is going to seize the throne and has rounded up everyone he thinks might argue.”

“And the princes?”

He is stammering with shock. “I don’t know. Richard could just kill them, like he killed Hastings. He could break into sanctuary and murder the whole royal family: the queen, the little girls, all of them. Today he has shown us that he can do anything. Perhaps they are already dead?”

News comes in snippets from the outside world, carried by housemaids as gossip from the market. Richard declares that the marriage between the queen, Elizabeth Woodville, and King Edward was never valid, as Edward was precontracted to another lady before he married Elizabeth in secret. He declares all their children bastards and himself as the only York heir. The craven Privy Council, who observe Hastings’s headless body being laid to rest beside the king he loved, do nothing to defend their queen and their princes, but there is a general hasty and unanimous agreement that there is only one heir, and it is Richard.

Richard and my kinsman Henry Stafford the Duke of Buckingham, start to put about that King Edward himself was a bastard, the misbegotten son of an English archer on Duchess Cecily while she was with the Duke of York in France. The people hear these accusations-what they make of them God knows-but there is no mistaking the arrival of an army from the northern counties, loyal to no one but Richard, and eager for rewards; there is no denying that all the men who might have been loyal to Prince Edward are arrested or dead. Everyone considers their own safety. No one speaks out.

For the first time in my life, I can think kindly of the woman I have served for nearly ten years, Elizabeth Woodville, who was Queen of England and one of the most beautiful and beloved queens that the country has ever had. Never beautiful to me, never beloved to me except now, fleetingly, in this moment of her utter defeat. I think of her in the damp dimness of the Westminster sanctuary, and I think that she will never triumph again, and for the first time in my life I can go on my knees and truly pray for her. All she has in her keeping now are her daughters; the life she reveled in has gone, and her two young sons are held by her enemy. I think of her defeated and afraid, widowed and fearing for her sons, and for the first time in my life I can feel my heart warm towards her: a tragic queen thrown down by no fault of her own. I can pray to Our Lady the Queen of Heaven to succor and comfort Her lost, miserable daughter in these days of her humiliation.

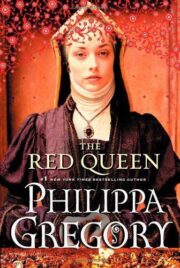

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.