I sway as if he has hit me. “How dare you! I have lived my life in His service!”

“He always tells you to strive for power and wealth. Are you quite sure it is not your own voice that you hear, speaking through the earthquake, wind, and fire?”

I bare my teeth at him. “I tell you that God will have my son Henry on the throne of England, and those who laugh now at my visions and doubt my vocation will call me ‘My Lady, the King’s Mother,’ and I shall sign myself Margaret Regina: Margaret R …”

There is an urgent tap on the door and the handle is rattled. “My lord!”

“Come in!” Thomas calls, recognizing the voice of his personal secretary.

I step aside as James Peers opens the door and slips in, sketches a bow to me, and approaches my husband’s writing table. “It is the king,” he says. “They are saying he is sick.”

“He was sick last night. Just overeating.”

“He is worse today; they have called more physicians and are bleeding him.”

“It is serious?”

“It seems so.”

“I’ll come at once.”

My husband throws down his pen and strides towards me, where I stand beside the half-open door. He comes close as a lover and puts his hand on my shoulder to breathe intimately in my ear. “If he were to be sick, if he were to die, and there were to be a regency and your boy were to return home and serve on the council of regency, then he would be two heartbeats only from the throne and standing beside it. If he were to be a good and loyal servant and attract the notice of men, they might prefer a young man and the House of Lancaster to that of a beardless mother’s boy and the House of York. Do you want to stay here and talk about your vocation, and whether you want affection, or do you want to come with me now and see if the York king is dying?”

I don’t even answer him. I slip my hand in the crook of his arm and we hurry out, our faces pale with concern for the king whom everyone knows we love.

He lingers for days. The agony of the queen is remarkable to see. For all his infidelities to her, and for all his fecklessness with his friends, this is a man who has inspired passionate attachment. The queen is locked in his chamber night and day; physicians go in and out with one remedy after another. The rumors fly around the court like crows seeking a tree in the evening. They say he was chilled by a cold wind off the river when he insisted on fishing at Eastertide. They say that he is sick in his belly from his constant overeating and excessive drinking. Some say that his many whores have given him the pox and it is eating away at him. A few think like me, that it is the will of God and punishment for treason against the House of Lancaster. I believe that God is making the way straight for the coming of my son.

Stanley takes to the king’s rooms, where men gather in corners to mutter their fears that Edward, who has been invincible for all his life, may finally have run out of luck. I spend my time in the queen’s rooms, waiting for her to come in, to change her headdress and comb her hair. I watch her blank face in the mirror as she lets the maid pin up her hair any way she chooses. I see her white lips moving constantly in prayer. If she were the wife of any other man, I would pray for her too from pity. Elizabeth is in agony of fear at losing the man she loves and the one who has stood above us all, unquestionably the greatest man in England.

“What does she say?” my husband asks me as we meet at dinner in the great hall, as subdued as if a funeral pall were laid over us already.

“Nothing,” I reply. “She says nothing. She is dumbstruck at the thought of losing him. I am certain he is sinking.”

That afternoon the Privy Council is called to the king’s bedside. We women wait in the great presence chamber, outside the privy chambers, desperate for news. My husband comes out after an hour, grim-faced.

“He swore us to an alliance over his bed,” he says. “Hastings and the queen: the best friend and the wife. Begged us to work together for the safety of his son. Named his son Edward as the next king, joined the hands of William Hastings and the queen over his bed. Said we should serve under his brother Richard as regent till the boy is of age. Then the priest came in to give him the last rites. He will be dead by nightfall.”

“Did you swear fealty?”

His crooked smile tells me that it meant nothing. “God, yes. We all swore. We all swore to work peaceably together, swore to friendship unending, so I should think the queen is arming now and sending for her son to come at once from his castle in Wales with as many men as he can muster, armed for war. I should think Hastings is sending for Richard, warning him against the Riverses, calling on him to bring in the men of York. The court will fall apart. Nobody can stand the ascendancy of the Riverses. They are certain to rule England through their boy. It will be Margaret of Anjou all over again, a court run by the distaff. Everyone will be calling on Richard to stop her. You and I must divide and work. I shall write to Richard and pledge fealty to him, while you assure the queen of our loyalty to her and to her family, the Riverses.”

“A foot in each camp at once,” I whisper. It is Stanley’s way. This is why I married him; this is the very moment that I married him for.

“My guess is that Richard will hope to rule England till Prince Edward is of age,” he says. “And then rule England through the boy if he can dominate him. He will be another Warwick. A Kingmaker.”

“Or will he be a rival king?” I breathe, thinking as always of my own boy.

“A rival king,” he agrees. “Duke Richard is a Plantagenet of York, already of age, whose claim to the throne is unquestionable, who does not need a regency nor an alliance of the lords to rule for him. Most people would think him a safer choice for king than an untried boy. Some will see him as the next heir. You must send a messenger to Jasper at once and tell him to keep Henry in safety till we know what will happen next. They cannot come to England till we know who will claim the throne.”

He is about to go, but I put a hand on his arm. “And what do you think will happen next?”

His eyes do not meet mine; he looks away. “I think the queen and Duke Richard will fight like dogs over the bone that is the little prince,” he says. “I think they will tear him apart.”

MAY 1483

Only four weeks after that hurried conversation I write to Jasper with extraordinary news.

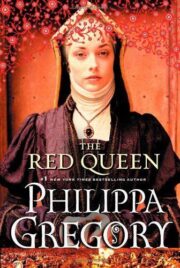

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.