Next to her is a most beautiful woman, perhaps the most beautiful woman I have ever seen. She is wearing a gown of blue with a silver thread running through, which makes it shimmer like water. You would think her scaled like a fish. She sees me staring at her, and she smiles back at me, which makes her face light up with a warm beauty like sunlight on water on a summer’s day.

“Who is that?” I whisper to my mother, who pinches my arm to remind me to be silent.

“Jacquetta Rivers. Stop staring,” my mother snaps, and pinches my arm again to recall me to the present. I curtsey very low and I smile at the king.

“I am giving your daughter in wardship to my dearly loved half brothers, Edmund and Jasper Tudor,” the king says to my mother. “She can live with you until it is time for her to marry.”

The queen looks away and whispers something to Jacquetta, who leans forwards like a willow tree beside a stream, the veil billowing around her tall headdress, to listen. The queen does not look much pleased by this news, but I am dumbfounded. I wait for someone to ask me for my consent so that I can explain that I am destined for a life of holiness, but my mother merely curtseys and steps back and then someone else steps forwards and it all seems to be over. The king has barely looked at me; he knows nothing about me, no more than he knew before I walked in the room, and yet he has given me to a new guardian, to another stranger. How can it be that he does not realize that I am a child of special holiness as he was? Am I not to have the chance to tell him about my saints’ knees?

“Can I speak?” I whisper to my mother.

“No, of course not.”

Then how is he to know who I am, if God does not hurry up and tell him? “Well, what happens now?”

“We wait until the other petitioners have seen the king, and then go in to dine,” she replies.

“No, I mean, what happens to me?”

She looks at me as if I am foolish not to understand. “You are to be betrothed again,” she says. “Did you not hear, Margaret? I wish you would pay attention. This is an even greater match for you. You are first going to be the ward, and then the wife, of Edmund Tudor, the king’s half brother. The Tudor boys are the sons of the king’s own mother, Queen Catherine of Valois, by her second marriage to Owen Tudor. There are two Tudor brothers, both great favorites of the king, Edmund and Jasper. Both half royal, both favored. You will marry the older one.”

“Won’t he want to meet me first?”

“Why would he?”

“To see if he likes me?”

She shakes her head. “It is not you they want,” she says. “It is the son you will bear.”

“But I’m only nine.”

“He can wait until you’re twelve,” she says.

“I am to be married then?”

“Of course,” she says, as if I am a fool to ask.

“And how old will he be?”

She thinks for a moment. “Twenty-five.”

I blink. “Where will he sleep?” I ask. I am thinking of the house at Bletsoe, which does not have an empty set of rooms for a hulking young man and his entourage, nor for his younger brother.

She laughs. “Oh, Margaret. You won’t stay at home with me. You will go to live with him and his brother, in Lamphey Palace, in Wales.”

I blink. “Lady Mother, are you sending me away to live with two full-grown men, to Wales, on my own? When I am twelve?”

She shrugs, as if she is sorry for it, but that nothing can be done. “It’s a good match,” she says. “Royal blood on both sides of the marriage. If you have a son, his claim to the throne will be very strong. You are cousin to the king, and your husband is the king’s half brother. Any boy you have will keep Richard of York at bay forever. Think of that; don’t think about anything else.”

AUGUST 1453

My mother tells me that the time will pass quickly, but of course it does not. The days go on forever and ever, and nothing ever happens. My half brothers and half sisters from my mother’s first marriage into the St. John family show no more respect for me now that I am to be married to a Tudor than when I was to be married to a de la Pole. Indeed, now they laugh at me going to live in Wales, which they tell me is a place inhabited by dragons and witches, where there are no roads, but just huge castles in dark forests where water witches rise up out of fountains and entrance mortal men, and wolves prowl in vast man-eating packs. Nothing changes at all until one evening, at family prayers, my mother cites the name of the king with more than her usual devotion, and we all have to stay on our knees for an extra half hour to pray for the health of the king, Henry VI, in this, his time of trouble; and beg Our Lady that the new baby, now in the royal womb of the queen, will prove to be a boy and a new prince for Lancaster.

I don’t say “Amen” to the prayer for the health of the queen, for I thought she was not particularly pleasant to me, and any child that she has will take my place as the next Lancaster heir. I don’t pray against a live birth, for that would be ill-wishing, and also the sin of envy; but my lack of enthusiasm in the prayers will be understood, I am sure, by Our Lady, who is Queen of Heaven and understands all about inheritance and how difficult it is to be one of the heirs to the throne, but a girl. Whatever happens in the future, I could never be queen; nobody would accept it. But if I have a son, he would have a good claim to be king. Our Lady Herself had a boy, of course, which was what everyone wanted, and so became Our Lady Queen of Heaven and could sign her name Mary Regina: Mary R.

I wait till my half brothers and half sisters have gone ahead, hurrying for their dinner, and I ask my mother why we are praying so earnestly for the king’s health, and what does she mean by a “time of trouble”? Her face is quite strained with worry. “I have had a letter from your new guardian, Edmund Tudor, today,” she says. “He tells me that the king has fallen into some sort of a trance. He says nothing, and he does nothing; he sits still with his eyes on the ground and nothing wakens him.”

“Is God speaking to him?”

She gives a little irritated sniff. “Well, who knows? Who knows? I am sure your piety does you great credit, Margaret. But certainly, if God is speaking to the king, then He has not chosen the best time for this conversation. If the king shows any sign of weakness, then the Duke of York is bound to take the opportunity to seize power. The queen has gone to parliament to claim all the powers of the king for herself, but they will never trust her. They will appoint Richard, Duke of York, as regent instead of her. It is a certainty. Then we will be ruled by the Yorks, and you will see a change in our fortunes for the worse.”

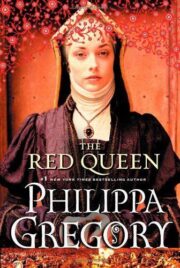

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.