“He is determined on war with France. He doesn’t want your boy rattling round on the border as a rival king, or a hostage, or whatever. He will let him come home, and he can even have his title. He will be Earl of Richmond.”

I can hardly breathe. “Praise God,” I say quietly. I long to get to my knees and thank God for sending the king some sense and mercy. “And his lands?”

“He won’t let him have Wales as a Tudor, that’s for sure,” Stanley says brutally. “But he will have to give him something. You might give him something from your dowry lands.”

“He should have his own,” I say, resentful at once. “I should not have to share my lands. The king should give him his own.”

“He will have to marry a girl of the queen’s choosing,” my husband warns me.

“He is not to marry some York makeweight,” I say, instantly irritated.

“He will have to marry whomever she picks out for him,” he corrects me. “But she has an affection for you. Why don’t you talk to her about who you would like? The boy has to marry, but they won’t allow him to marry anyone who would strengthen his Lancaster line. It will have to be a York. If you were to put your mind to it, he might have one of the York princesses. There are enough of them, God knows.”

“Can he come at once?” I breathe.

“After the Christmas feast,” my husband says. “They will need to be reassured, but the main work is done. They trust you, and they trust me, and they believe we would not introduce an enemy into their kingdom.”

It has been so long since we discussed this that I am not sure that he still shares my silent will. “Have they forgotten that he might be a rival king?” I ask. We are in my own room, but still I drop my voice to a whisper.

“Of course he is a rival king,” he says steadily. “But while Edward the king lives, there can be no chance of a throne for him. No one in England would follow a stranger against Edward. When Edward dies, there is Prince Edward, and should anything happen to him, Prince Richard to come after him, beloved boys of a strong ruling house. It is hard to imagine how your Henry could step into a vacant throne. He would have to walk past three coffins. He would have to see the death of a great king and two royal boys. That would be an unlucky set of accidents. Or would he have the stomach to enact such a thing? Would you?”

APRIL 1483

I have to wait till Easter for Henry to come home, though I write to him and to Jasper at once. They start to prepare for his return, dispersing the little court of York opportunists and desperate men who have gathered around them, preparing themselves to part for the first time since Henry’s boyhood. Jasper writes to me that he cannot think what he will do with himself without Henry to guide, advise, and govern.

Perhaps I will go on pilgrimage. Perhaps it is time I considered myself, my own soul. I have lived only for our boy and, far from England as we have been, I had come to think that we would never get home. Now he will return, as he should, but I cannot. I will have lost my brother, my home, you, and now him. I am glad that he can come back to you and take his place in the world. But I shall be very alone in my exile. Truly, I cannot think what I shall do without him.

I take this letter to Stanley, my husband, where he is working in his day room, papers piled around the table for his assent. “I think Jasper Tudor would be glad to come home with Henry,” I say cautiously.

“He can come home to the block,” my husband says bluntly. “Tudor picked the wrong side and clung to it through victory all the way to defeat. He should have sought for pardon after Tewkesbury when everyone else did, but he was as stubborn as a Welsh pony. I’ll use no influence of mine to have him restored, and neither will you. Besides, I think you have an affection for him which I don’t share, nor do I admire it in you.”

I look at him in utter amazement. “He is my brother-in-law,” I say.

“I am aware of that. It only makes it worse.”

“You can’t think that I have been in love with him for all these years of absence?”

“I don’t think about it at all,” he says coldly. “I don’t want to think about it. I don’t want you to think about it. I don’t want him to think about it, and especially, I don’t want the king and that gossip his wife to think about it. So Jasper can stay where he is, we will not intercede for him, and you will have no need to write to him anymore. You need not even think of him. He can be dead to us.”

I find I am trembling with indignation. “You can have no doubt as to my honor.”

“No, I don’t want to think about your honor, either,” he repeats.

“Since you have no desire for me yourself, I don’t see why you should care one way or the other!” I throw at him.

I cannot anger him. His smile is cold. “The lack of desire, you will recall, was required by our marriage agreement,” he says. “Stipulated by you. I have no desire for you at all, my lady. But I have a use for you, as you do for me. Let us stay with this arrangement and not confuse it with words from a romance that neither of us could ever mean to each other. As it happens you are not to my taste as a woman, and God knows what sort of man could raise desire in you. If any. I doubt that even poor Jasper caused more than a chilly flutter.”

I sweep to the door but pause with my hand on the latch to turn back and speak bitterly to him: “We have been married for ten years, and I have been a good wife to you. You have no grounds for complaint. Have you not the slightest affection for me?”

He looks up from his seat at the table, his quill poised over the silver inkpot. “You told me when we married that you were given to God and to your cause,” he reminds me. “I told you I was given to the furtherance of myself and my family. You told me that you wished to live a celibate life, and I accepted this in a wife who brought a fortune, a great name, and a son who has a claim to the throne of England. There is no need for affection here; we have a shared interest. You are more faithful to me for the sake of our cause than you would ever be for any affection, I know that. If you were a woman who could be ruled by affection, you would have gone to Jasper and your son a dozen years ago. Affection is not important to you, nor to me. You want power, Margaret, power and wealth; and so do I. Nothing matters as much as this to either of us, and we will sacrifice anything for it.”

“I am guided by God!” I protest.

“Yes, because you think God wants your son to be King of England. I don’t think your God has ever advised you otherwise. You hear only what you want. He only ever commands your preferences.”

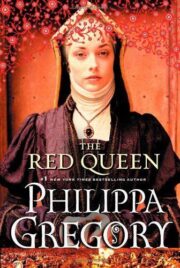

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.