The first time he took me to court to present me, as his wife, I was surprised to find that I was more nervous than when I went to court to meet a real monarch. She was nothing but the widow of a country squire; but this usurping queen has dominated my life, and her fortunes have risen unstoppably while mine have struggled. We have been on opposite sides of fortune’s wheel, and she has risen and risen while I have fallen. She has overshadowed me; she has lived in the palaces that should have been my homes; she has worn a crown that should have been mine. She has been draped in ermine for no better reason than she is beautiful and seductive, whereas those furs are mine by right of birth. She is six years older than me, and she has always been ahead of me. She was on the side of the road when the York king came riding by. The very year that he saw her, fell in love with her, married her, and made her his queen was the year that I had to leave my son in my enemy’s keeping, live with a husband whom I knew would not father my son, nor fight for my king. While she wore headdresses that grew higher and higher, draped them with the finest lace, commissioned gowns trimmed with ermine, had songs dedicated to her beauty, rewarded winners of tournaments, and conceived a child every year, I went to my chapel and got to my knees and prayed that my son, though raised in my enemy’s house, would not become my enemy. I prayed that my husband, though a coward, would not become a turncoat. I prayed that the power of Joan would stay with me and I would find the strength to be constant to my family, my God, and myself. All those long years, while my son Henry was raised by the Herberts and I was powerless to do anything but be a good wife to Stafford, this woman spent planning marriages for her family, plotting against her rivals, consolidating her hold over her husband, and dazzling England.

Even in the months of her eclipse, when she was in sanctuary and my king was back on the throne and we sailed down the river to the king’s court and he recognized my boy as Earl of Richmond, even in that darkness she snatched her moment of triumph, for there she gave birth to her first boy, the baby whom we are now to call the Prince of Wales, Prince Edward, and so gave hope to the Yorks.

In everything, even in her moments of apparent defeat, she has triumphed over me, and I must have prayed for nearly twenty years that she should learn the true humility of Our Lady that comes only to those who suffer, and yet I have never seen her improved by hardship.

Now she stands before me, the woman they call the most beautiful in England, the woman who won a throne on her looks, the woman who commands her husband’s adoration and the admiration of a nation. I drop my eyes as if in awe. God Himself knows that she doesn’t command me.

“Lady Stanley,” she says pleasantly to me as I curtsey low and rise up.

“Your Grace,” I say. I can feel the smile on my face stretched so hard that my mouth is drying with the effort.

“Lady Stanley, you are welcome to court on your own account, as well as that of your husband, who is such a good friend to us,” she says. All the time her gray eyes are taking in my rich gown, my wimplelike headdress, my modest stance. She is trying to read me, and I, standing before her, am trying with every inch of my being to hide my righteous hatred of her, her beauty, and her position. I am trying to look agreeable, while I can feel my proud belly turn over with jealousy.

“My husband is happy to serve his king and your house,” I say. I swallow in a dry throat. “As am I.”

She leans forwards, and in her readiness to hear me, I suddenly realize that she wants to believe that I have turned my own coat and am ready to be loyal to them. I see her desire to befriend me, and behind this, her fear that she will never be wholly safe. Only if she has friends in every house in England can she be sure that the houses will not rise against her again. If she can teach me to love her, then the House of Lancaster loses a great leader: me, the heiress. She must have broken her heart and lost her wits in sanctuary. When her husband had to flee for his life and my king was on the throne, she must have been so frightened that now she longs for any friendship: even mine, especially mine.

“I shall be glad to count you among my ladies and my friends,” she says graciously. Anyone would think she was born to be a queen instead of a penniless widow; she has all the style of Margaret of Anjou, and far more charm. “I am glad to offer you a position at court, as one of my ladies-in-waiting.”

I picture her as a young widow, standing at the roadside waiting for a lustful king to ride by, and for a moment I fear that my contempt will show in my face. “I thank you.” I drop my head as I curtsey very low again, and get myself out of her presence.

It is strange for me to smile and bow to my enemy and try to keep the resentment out of my eyes. But over ten years in service to them I learn how to do it so well that no one knows I whisper to God that He must not forget me in my enemies’ house. I learn to pass for a loyal courtier. Indeed, the queen grows fond of me and trusts me as one of her intimate ladies-in-waiting, who sit with her during the day, dine at her ladies’ table at night, dance before the court, and accompany her to her gorgeously furnished rooms. Edward’s brother, George, plots against the royal couple, and she clings to us, her ladies, when her husband’s family are divided. She has a nasty moment when she is accused of witchcraft and half the court are laughing up their sleeves and the other half crossing themselves when her shadow falls on them. She has me at her side when George goes to his death in the Tower, and I can feel the court shudder with fear at a royal house divided against itself. I hold her hand when they bring news of his death, and she thinks that at last she is safe from his enmity. She whispers to me, “God be praised he is gone,” and all I think is: yes, now he is gone, his title, which once belonged to my son, is free once more. Perhaps I can persuade her to give it back?

When the Princess Cecily was born, I was in and out of the confinement chamber, praying for the queen’s safety and for that of the new baby; and then it was me she asked to stand as godmother to the new princess, and it was I who carried the tiny girl, in my arms, to the font. I, the favorite of all her noble ladies.

Of course, the queen’s constant childbearing, almost every year, reminds me of the child I had but was never allowed to raise. And once a month, through the long ten years, I have a letter from that son, first a youth, and then a man, and then, I realize, a man reaching his majority: a man old enough to make good his claim to be king.

Jasper writes that he has maintained Henry’s education; the young man still follows the offices of the church, as I ordered. He jousts, he hunts, he rides, he practices archery, tennis, swimming-all the sports that will keep his body healthy and strong and ready for battle. Jasper has him study accounts of wars, and no veteran soldier visits them but Jasper has him talk to Henry about the battle he saw, and how it could have been won or done differently. He has masters to teach him the geography of England so that he may know the country where his ships will land; he studies the law and the traditions of his home so that he may be a just king when his day comes. Jasper never says that teaching a young man in exile from the country that he may never see, preparing him for a battle that may never be joined, is weary work; but as King Edward of England celebrates the twenty-first year of his reign with a glorious Christmas at Westminster Palace, attended by his handsome and strong son, Prince Edward of Wales, we both sense that it is work without purpose, work without chance of success, work without future.

Somehow, over the ten years of my marriage with Thomas Stanley, my son’s cause has become a forlorn hope even to me. But Jasper, far away in Brittany, keeps the faith; there is nothing else he can do. And I keep the faith, for it burns inside me that it should be a Lancaster on the throne of England, and my boy is the only Lancaster heir, but for my nephew the Duke of Buckingham, left to us. And the duke is married into the Woodville family and so yoked to York, while Henry, my son, keeps the faith-for though he is twenty-five, he has been raised in hope, however faint, and though he is a man grown, he has not yet the independence of thought to tell his beloved guardian Jasper, or me, that he will deny our dream, which has cost him his childhood, and still holds him in thrall.

Then, just before the Christmas feast, my husband Thomas Stanley comes to my room in the queen’s apartment and says: “I have good news. I have made an agreement for the return of your son.”

I drop the sacred Bible from my hands and snatch it before it slips from my lap. “The king has never agreed?”

“He has agreed.”

I am stammering in my joy and relief. “I never thought he would-”

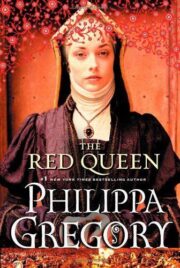

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.