I look at myself in the mirror before I go down to him, and I feel once again my fruitless irritation at the York queen. They say she has wide gray eyes, but I have only brown. They say she wears the tall, conical hats sweeping with priceless veils that make her appear seven feet tall; and I wear a wimple like a nun. They say she has hair like gold, and mine is brown like a thick mane on a hill pony. I have trained myself in the holy ways, in the life of the spirit, and she is filled with vanity. I am tall like her, and I am slim from fasting on holy days. I am strong and brave, and these should be qualities that a man of sense might look for in a woman. For see: I can read, I can write, I have several translations from the French to my credit, I am learning Latin and I have composed a small book of my own prayers, which I have had copied and given to my household commanding them to be read morning and night. There are few such women-indeed is there another woman in the country who can say as much? I am a highly intelligent, highly educated woman, from a royal family, called by God to great office, guided personally by the Maid, and constantly hearing the voice of God in my prayers.

But I am well aware that these virtues count as nothing in the world where a woman like the queen is praised to the skies for the allure of her smile and for the easy fecundity of her cream-fed body. I am a thoughtful, plain, ambitious woman. And today, I have to wonder if this will be enough for my new husband. I know-who should know better than I, who have been disregarded all my life? – that spiritual riches do not count for much in the world.

We dine in the hall before my tenants and servants, and so we cannot talk privately till he comes to my chambers after dinner. My ladies are sewing with me, and one is reading from the Bible as he comes in and he takes his seat without interrupting her, listening till she comes to the end of the passage, with his head bowed. So he is a godly man, or at any rate, hoping to pass as one. Then I nod them to stand aside, and he and I sit by the fire. He takes the seat where my husband Henry used to sit in the evening, talking of nothing of importance, cracking walnuts and throwing the shells into the hearth; and for a moment, I feel a renewed sense of surprising loss for that comfortable man who had the gift of innocents: being happy in a little life.

“I hope I will please you as a wife,” I say quietly. “I thought it would be an arrangement that would suit us both equally.”

“I am glad that you thought of it,” he says politely.

I hesitate. “I believe my advisors made it clear to you that I intend that there should be no issue from our marriage?”

He does not look up at me; perhaps I have embarrassed him by being too blunt. “I understood that the marriage will be binding but unconsummated. We will share a bed tonight, to complete the contract, but that you regard yourself as celibate as a nun?”

I take a little breath. “I hope that is agreeable to you?”

“Perfectly,” he says coldly.

For a moment, looking at his down-turned face, I wonder if I really want him to agree so readily that he will be my husband but never my lover. Elizabeth the queen, a woman six years older than me, is bedded passionately by her husband, who demonstrates his lust for her with a new baby almost every year. I was infertile with Henry Stafford when I endured his infrequent intimacy; but perhaps I might have had another chance with this husband, himself a father, if I had not ruled it out before we had even met.

“I believe I have been chosen by God for a higher purpose,” I explain, almost as if inviting an argument. “And that it is His will that I am prepared for it. I cannot be a mistress to a man, and a servant of God.”

“As you wish,” he says, as if he is indifferent.

I want him to understand that this is a calling. I suppose, somehow for some reason, I want him to try to persuade me to be his wife indeed. “I believe that God chose me to bear the next Lancaster King of England,” I whisper to him. “And I have dedicated my life to keeping my son in safety, and I have sworn a holy vow that I will put him on the throne, whatever it costs me. I will have only one son; I am devoted to his success alone.”

At last he looks up, as if to confirm that my face is shining with holy purpose. “I think I made it clear to your advisors that you will be required to serve the House of York: King Edward and Queen Elizabeth?”

“Yes. I made it clear to yours that I want to be at court. It is only with the king’s favor that I can bring my son home.”

“You will be required to come to court with me, to take up a place in the queen’s chamber, to support me in my work as their preeminent courtier and advisor, and to be to all appearances a loyal and faithful member of the House of York.”

I nod, not taking my eyes from his face. “This is my intention.”

“There must be no shadow of doubt or anxiety in their mind from the first day to the last,” he rules. “You must make them trust you.”

“It will be an honor,” I lie boldly, and I see from the gleam of amusement in his brown eyes that he knows I have steeled myself to come to this point.

“You are wise,” he says so softly that I can hardly hear him. “I think he is invincible, for now. We will have to cut our coats to suit our cloth, and wait and see.”

“Will he really accept me at his court?” I ask, thinking of the long struggle that Jasper has waged against this king, and that even now Wales is still uneasy under the York rule, and Jasper waiting in Brittany for good times to come, guarding my boy who should be king.

“They are eager to heal the wounds of the past. They are desperate for friends and allies. He wants to believe that you have joined my house and his affinity. He will meet you as my wife,” Lord Stanley replies. “I have spoken to him of this marriage, of course, and he wishes us well. The queen too.”

“The queen? She does?”

He nods. “Without her goodwill, nothing happens in England.”

I force a smile. “Then I suppose I shall have to learn to please her.”

“You will. You and I may have to live and die under York rule. We have to come to terms with them, and-better yet-rise in their favor.”

“Will they let me bring my son home?”

He nods. “That is my plan. I have not asked for it yet, and I won’t for a while-until you are established at court and they start to trust you. You will find them eager to trust and to like people. They are truly charming. You will find them welcoming. Then we will see what we can do for your son, and what rewards he can offer me. How old is he now?”

“He is just fifteen,” I say. I can hear the longing in my voice as I think of my boy growing into manhood unseen. “His uncle Jasper has him safely in Brittany.”

“He will have to leave Jasper,” Lord Stanley warns. “Edward will never reconcile with Jasper Tudor. But I would have thought they would let your son come home, if he was ready to swear loyalty to them, and we gave our word he would cause no trouble, resign his claims.”

“George, Duke of Clarence, has taken my son’s title of Earl of Richmond,” I remark jealously. “My son must come home to his rights. He has to have his title and lands when he comes home. He must come home as the earl that he is.”

“George has to be kept sweet,” Lord Stanley says bluntly. “But we might buy him off in some way, or make some arrangement. He is as greedy as a boy in the pastry kitchen. He is disgustingly venal. And he is as trustworthy as a cat. We can no doubt bribe him with something from our shared fortune. After all, between the two of us, we are very great landowners.”

“And Richard, the other brother?” I ask.

“Loyal as a dog,” Lord Stanley replies. “Loyal as a hog. Loyal as the hog of his badge. Heart and soul, Edward’s man. He hates the queen, so there is the one small crack in the court, if one wanted to find a fault. But you would be hard put to force the sharpest tip of a dagger in there. Richard loves his brother and despises the queen. William Hastings, the king’s great friend, is the same. But what is the use of looking for cracks in a house so staunch? Edward has a handsome, strong boy in the cradle and good reason to hope for more. Elizabeth Woodville is a fecund wife. The Yorks are here to stay, and I am working to be their most trusted subject. As my wife you must learn to love them as I do.”

“From conviction?” I ask, as softly as he.

“I am convinced for now,” he says, quiet like a snake.

1482

I learn a new rhythm of life with this new husband, as the years go round, and though he teaches me to be as good a courtier to this royal family as I and mine always were to the true royal house, I never change; I always despise them. We have a great London house, and he rules that we will spend most of the winter months at court, where he waits daily on the king. He is a member of the Privy Council, and his advice to the king is always cautious and wise. He is highly regarded for his thoughtfulness and his knowledge of the world. He is particularly careful always to be as good as his word. Having changed sides once in his life, he wants to make sure that the Yorks believe that he will never do it again. He wants to be indispensable: trustworthy as a rock. They nickname him “the fox” in tribute to his caution, but nobody doubts his loyalty.

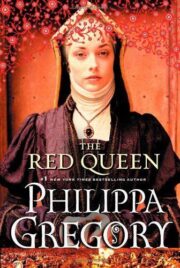

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.