“What?”

“He has snapped up the other Warwick heiress, the sister of Isobel who is married to George. He has married Anne Neville, the widow of the Prince of Wales, Edward the Prince of Wales that was. He who died at Tewkesbury.”

“How could he?” I demand. “Her mother would never let such a thing happen. How would even George let it happen? Anne is heiress to the Warwick estates! He’s not likely to let his younger brother have her! He won’t want Richard sharing the Warwick fortune! Their lands! The loyalty of the north!”

“Didn’t know,” my steward gurgles from the bottom of his tankard. “They say that Richard went to George’s house, found Lady Anne there in hiding, took her away, hid her himself, and married her without even permission from the Holy Father. At any event, the court is in uproar at Richard taking her to wife; but he has her, the king will forgive him, and there is no new husband for you, my lady.”

I am so furious that I don’t dismiss him but stride from the room, leaving him there with his ale in his hand like a dolt. To think that I was considering young Richard and all the time he was courting and capturing a Warwick girl, and now the York family and the Warwick family are all nicely tied in together and I am excluded. I feel as offended as if I had proposed to him myself and been rejected. I was truly preparing to lower myself to marry one of the House of York-and then I find that he has taken young Anne to bed and it is all over.

I go to the chapel and drop down on my knees to take my complaints to Our Lady, who will understand how insulting it is to be overlooked, and for such a weak thing as Anne Neville. I pray with irritation for the first hour, but then the calm of the chapel comes to me, the priest comes in for the evening prayers, and the familiar ritual of the service soothes me. As I whisper the prayers and run my rosary beads through my fingers, I wonder who else might be the right age, and unmarried and powerful at the court of York, and Our Lady in her particular care for me sends me a name as I say “Amen.” I rise to my feet and leave the chapel with a new plan. I think I have the very man who would turn his coat to the winning colors and I whisper his name to myself: Thomas, Lord Stanley.

Lord Stanley is a widower born loyal to my House of Lancaster, but never very certain in his preference. I remember Jasper complaining that at the battle of Blore Heath, Stanley swore to our queen, Margaret of Anjou, that he would be there for her, with his two thousand men, and she waited and waited for him to come and take the victory for her, and while she was waiting for him, York won the battle. Jasper swore that Stanley was a man who would take out all his affinity in battle array-an army of many thousands of men-and then sit on a hill to see who was going to win before declaring his loyalty. Jasper said he was a specialist of the final charge. Whichever was the victor, they were always grateful to Stanley. This is a man whom Jasper would despise. This is a man whom I would have despised. But now it may be that this is the very man I need.

He turned his coat after the battle of Towton to become a York and rose high in favor with King Edward. He is now steward of the royal household, as close to the king as it is possible to get, and is rewarded with great lands in northwest England that would make a fine match with my own lands, and might make a good inheritance for my son Henry in the future, though Stanley has children and a grown son and heir of his own already. King Edward seems to admire and trust him, though my suspicion is that the king is (and not for the first time) mistaken. I would not trust Stanley further than I could watch him, and if I did, I would still keep an eye on his brother. As a family they have a tendency to divide and join opposing sides to ensure that there is always one who wins. I know him as a proud man, a cold man, a man of calculation. If he were on my side, I would have a powerful ally. If he were Henry’s stepfather, I might hope to see my boy home in safety and restored to his titles.

Without mother or father to represent me, I have to apply to him myself. I am twice widowed, and a woman of nearly thirty years. I think it is time that I might take my life into my own keeping. Certainly, I know that I should have waited for a full year of mourning before I approached him; but once I had thought of him, I was afraid that the queen would snap him up in a marriage to benefit her family if I left him too long, and besides, I want him working to get Henry home at once. I am not a lady of leisure who has years to mull over plans. I want things done now. I don’t have the queen’s ill-gotten advantages of beauty and witchcraft-I have to do my work with honesty and speed.

And in any case, his name came into my mind when I was on my knees in chapel. Our Lady Mother Herself guided me to him. The will of God is that I should find in him a husband for me and an ally for my son. I think I will not trust John Leyden this time. Joan of Arc did not find a man to do her work for her; she rode out in her own battles. So I write to Stanley myself and propose a marriage between ourselves in as simple and as honest terms as I can manage.

I have some nights of worry that I will disgust him by being so blunt about my plans. Then I think of Elizabeth Woodville waiting for the King of England under an oak tree, as if she just happened to be by the roadside, a hedge witch casting her spells, and I think that my way at least is an honorable offer and not a begging for an amorous glance and a sluttish strutting of her well-worn wares. Then at last he writes in reply. The steward of his household will meet mine in London, and if they can agree on a marriage contract, he will be delighted to be my husband at once. It is as simple and as cold as a bill of sale. His letter is as cool as an apple in a store. We have an agreement, but even I note that it does not feel much like a wedding.

The stewards, and then the bailiffs, and then finally the lawyers meet. They wrangle, they agree, and we are to be married in June. It is no little decision for me-for the first time in my life I have my own lands in my own hands as a widow; once I am a wife, everything becomes Lord Stanley’s property. I have to struggle to reserve what I can from the law that rules that a wife has no rights, and I keep what I can, but I know I am choosing my master.

JUNE 1472

We meet only the day before the wedding, in my house-now his house-at Woking, so it is just as well that I find him well made, with a brown, long face; thinning hair; a proud bearing; and dressed richly-the Stanley fortune showing in his choice of embroidered cloth. There is nothing here to make the heart leap, but I want nothing to make my heart leap. I want a man whom I can rely on to be false-hearted. I want a man who looks as if he can be trusted, and yet is not trustworthy. I want an ally and a coconspirator, I want a man who comes naturally to double-dealing, and when I see his straight eyes, and his sideways smile, and his general air of self-importance, I think: here I have one.

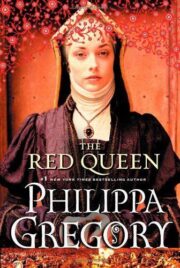

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.