Even if my husband’s dying advice proves right, and there is no future for Henry as King of England, then I still have to claim his earldom and try to get his lands returned to him. This is the road I have to take now. If I am to serve my family and serve my son, I will have to place myself in the court of York, whatever I think of Edward and his enchanting queen. I will learn to smile at my enemies. I will have to find myself a husband who has influence with them, who can take me to the highest place in the land, but still has the sense to think for himself and serve his own ambition and mine.

APRIL 1472

I take a month to consider the court of York, the court of hedge-rose usurpers, and wonder which of the men favored by the king would be most likely to protect me and my lands and bring my son home in safety. William, now ennobled as Lord Hastings, the king’s best friend and companion, has a wife already, and is in any case heart and soul for Edward. He would never consider a stepson’s interest against the king he loves. He would never turn his coat against York, and I have to marry a man who is prepared to be true to my cause. At the very best, I want a husband who is ready to turn traitor. The queen’s brother, Sir Anthony Woodville, the new Earl Rivers, would be of interest, except that he is notoriously loyal and loving to his sister. Even if I could bear to marry into the upstart family of a queen who found her husband by standing at the roadside like a whore, I could not turn any of her family against her and against their darling baby boy. They stick together like the brigands they are. The Riverses run together-everyone says it. Always downhill, of course.

I consider the king’s brothers. I don’t think I am looking too high. After all, I am the heiress to the House of Lancaster; it would make sense for York to approach me and heal the wounds of the war through marriage. George, the next brother to the king, the practiced turncoat, is already married to Warwick’s eldest daughter Isobel, who must rise up every morning to regret her father’s ambition in pairing her with this vain fool; but Richard, the younger brother, is still free. He is nearly twenty years old, so there would be eight years between us, but worse matches have been made. All that I hear of him is that he is faithfully loyal to his brother; but once married to me, with an heir to the throne as his stepson, how could any young man resist treasonous ambition, especially a York?

But the fact that I cannot have Edward the King just eats into me, day after day, as I consider the men I could marry. If only Edward had not been entrapped by the beautiful Elizabeth Woodville, he would have made the perfect match for me now. The York boy, and the Lancaster heiress! Together we could have healed the wounds of our country and made my son the next king. By marrying, we would have unified our houses and put an end to rivalry and war. I care nothing for his good looks as I am devoid of vanity and lust, but the rightness of being his wife and becoming Queen of England haunts me like a lost love. If it were not for Elizabeth Woodville and her shameless capture of a young man, it could be me at his side now, Queen of England, signing my letters: Margaret R. They say that she is a witch and captured him with spells and married him on May Day-whatever the truth of that, I can clearly see how she has circumvented the will of God by seducing the man who could have made me queen. She must be a woman beyond wickedness.

But it is pointless to mourn, and anyway Edward would be a hard husband to respect. How could one bear to obey a man constantly bent on pleasure? What might he command a wife to do? What vices might he embrace? If he bedded a woman, what dark and secret pleasures might he insist on? It makes me shudder to think of Edward naked. I hear he is quite without morals. He bedded his upstart wife and wedded her (probably in that order), and now they have a handsome strong son to claim the throne that rightfully belongs to my boy, and no chance of her dying in childbed while she is guarded by her mother, who is without doubt a witch. No chance for me at all unless I can creep close to the throne through his young brother Richard. I would not stand in the road and try to tempt him like his brother’s wife did; but I might make a proposal that would interest him.

I send my steward, John Leyden, to London with instructions to befriend and dine with the head of Richard’s household. He is to say nothing, but see how the land lies. He must see if the young prince has a betrothal in mind, discover if he would be interested in my land holdings in Derbyshire. He is to whisper in his ear that a Tudor stepson whose name commands all of Wales is a boy worth fathering. He is to wonder aloud if Richard’s heartfelt fidelity to his brother might waver so far as to marry into the enemy house, if the terms were right. He is to see what the young man might take as a price for the wedding. He is to remind him that though I am eight years his senior, I am still slim and comely and not yet thirty years old; some would say that I am pleasing. Perhaps I could even be seen as beautiful. I am no golden-haired whore of his brother’s choosing, but I am a woman of dignity and grace. For one moment only I think of Jasper’s hand on my waist on the stair at Pembroke and his kiss on my mouth before we drew back.

My steward is to emphasize that I am devout, and that no woman in England prays with more fervor or goes on more pilgrimages, and that though he may think this is nothing (after all, Richard is a young man and from a foolish family), to have a wife who has the ear of God, whose destiny is guided by the Virgin herself, is an advantage. It is something to have a woman leading your household who has had saints’ knees from childhood.

But it is all for nothing. John Leyden comes home on his big bay cob and shakes his head at me as he dismounts before the front door of the house at Woking.

“What?” I snap without further greeting, though he has ridden far, and his face is red from the heat of May. A page runs towards him with a foaming tankard of ale, and he buries his face in it, as if I am not waiting, as if I do not thirst and fast all Friday, every week, and on holy days too.

“What?” I repeat.

“A word in private,” he says.

So I know that it is bad news, and I lead the way, not to my private rooms, where I don’t want a hot sweaty man drinking ale, but to the chamber on the left of the great hall, where my husband used to do the business of his lands. Leyden closes the door behind him and finds me before him, my face hard. “What went wrong? Did you botch it?”

“Not I. It was a botched plan. He is married already,” he says, and takes another draft.

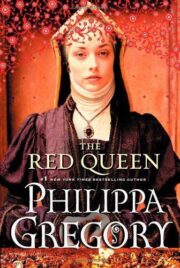

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.