Amazingly, Edward gets to London without a single obstacle in his path, the gates are thrown open for him by the adoring citizens, and he is reunited with his wife, as if he had never been chased from his own land, running for his life.

I take to my chamber and pray on my knees when I hear this news from Somerset’s hard-riding messenger. I think of Elizabeth Woodville-the so-called beauty-with her baby son in her arms, and her daughters all around her, starting up as the door is thrown open and Edward of York strides into the room, victorious as he always is. I spend two long hours on my knees, but I cannot pray for victory and I cannot pray for peace. I can only think of her running into his arms, knowing that her husband is the bravest and most able man in the kingdom, showing him her son, surrounded by their daughters. I take up my rosary and pray again. The words are for the safety of my king; but I cannot think of anything but my jealousy that a woman, far worse born than me, far worse educated than me, without doubt less beloved by God than me, should be able to run to her husband with joy and show him their son and know he will fight to defend him. That a woman such as her, clearly not favored by God, showing no signs of grace (unlike me), should be Queen of England. And that, by some mystery-too great for me to understand-God should have overlooked me.

I come out of my chamber and find my husband in the great hall. He is seated at the top table, his face grave. His steward, standing beside him, is putting one sheet of paper after another before him for his signature. His clerk beside him is melting wax and pressing in the seal. It takes me only a moment to recognize the commissions of array. He is calling up his tenants. He is going to war; at last he is going to war. I feel my heart lift like a lark at the sight; God be praised, he is owning his duty and going to war at last. I step up to the table, my face glad.

“Husband, God bless you and the work you are finally doing.”

He does not smile back at me; he looks at me wearily, and his eyes are sad. His hand keeps moving, signing Henry Stafford, time after time, and he hardly glances down at his pen. They come to the last page: the clerk drips wax, stamps the seal, and hands it in its box back to his chief secretary.

“Send them at once,” Henry says.

He pushes back his chair and steps off the little dais to stand before me, takes my hand, and tucks it in his arm and walks me away from the clerk, who is gathering up the papers to take to the stables for the waiting messengers.

“Wife, I have to tell you a thing which will trouble you,” he says.

I shake my head. I think he is about to tell me that he is going to war with a heavy heart for fear of leaving me, and so I rush to reassure him that I fear nothing when he’s doing God’s work. “Truly husband, I am glad …” He stills me with a gentle touch on my cheek.

“I am calling up my men not to serve King Henry, but to serve King Edward,” he says quietly.

At first I hear the words, but they make no sense to me. Then I am so frozen with horror that I say nothing. I am so silent that he thinks I have not heard him.

“I will serve King Edward of York, not Henry of Lancaster,” he says. “I am sorry if you are disappointed.”

“Disappointed?” He is telling me he has turned traitor, and he thinks I may be disappointed?

“I am sorry for it.”

“But my cousin himself came to persuade you to war …”

“He did nothing but convince me that we have to have a strong king who will put an end to war, now and forever, or he and his sort will go on until England is destroyed. When he told me that he would fight forever, I knew that he would have to be defeated.”

“Edward is not born to be king. He is not a bringer of peace.”

“My dear, you know that he is. The only peace we have known in the last ten years was when he was on the throne. And now he has a son and heir, so please God the Yorks will hold the throne forever and there will be an end to these unending battles.”

I wrench my hand away from his grip. “He is not born royal,” I cry. “He is not sacred. He is a usurper. You are calling out your tenants and mine, my tenants from my lands to serve a traitor. You would have my standard, the Beaufort portcullis, unfurled on the York side?”

He nods. “I knew you would not like it,” he says resignedly.

“I would rather die than see this!”

He nods as if I am exaggerating, like a child.

“And what if you lose?” I demand. “You will be known as a turncoat who supported York. Do you think they will call Henry-your stepson-to court again, and give him back his earldom? Do you think Henry the king will bless him as he did before, when everyone knows you have shamed yourself, and shamed me?”

He grimaces. “I think it is the right thing to do. And, as it happens, I think York will win.”

“Against Warwick?” I ask him scornfully. “He can’t beat Warwick. He didn’t do so well last time, when Warwick chased him out of England. And the time before that, when Warwick took him prisoner. He is Warwick’s boy, not his master.”

“He was betrayed last time,” he said. “He was alone without his army. This time he knows his enemies, and he has summoned his men.”

“Say you win then,” I say, the words tumbling out in my distress. “Say you put Edward on my family’s throne. What happens to me? What happens to Henry? Will Jasper have to go into exile again, thanks to your enmity? Will my son and his uncle be driven out of England by you? Do you want me to go too?”

He sighs. “If I serve Edward and he is glad of my service, then he will reward me,” he says. “We might even get Henry’s earldom back from him. The throne will no longer run in your family, but Margaret, dear little wife, to be honest with you: your family does not deserve to own it. The king is sick, to tell the truth; he is mad. He is not fit to run a country, and the queen is a nightmare of vanity and ambition. Her son is a murderer: Can you think what we will suffer if he ever gets the throne? I cannot serve such a prince and such a queen. There is no one but Edward. The direct line is-”

“Is what?” I spit.

“Insane,” he says simply. “Hopeless. The king is a saint and cannot rule, and his son is a devil and should not.”

“If you do this, I will never forgive you,” I swear. The tears are running down my face, and angrily I brush them away. “If you ride out to defeat my own cousin, the true king, I will never forgive you. I will never call you ‘husband’ again; you will be as if you were dead to me.”

He releases my hand as if I am a bad-tempered child. “I knew you would say that,” he says sadly. “Though I am doing what I think best for us both. I am even doing what I think best for England, which is more than many men can say in these troubled times.”

APRIL 1471

The summons comes from Edward the usurper in London, and my husband rides out at the head of his army of tenants to join his new lord. He is in such a hurry to go that half the men are not yet equipped, and his master of horse stays behind to see that the sharpened staves and newly forged swords are loaded in carts to follow the men.

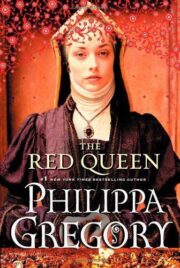

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.