This King Edward is a young man of nineteen, just a year older than me, surviving the death of his father as I have done, dreaming of greatness as I do-and yet he has put himself at the head of his house’s army and led them to the throne of England, while I have done nothing. It is he who has been a Joan of Arc for England, not me. I cannot even hold my son in my own keeping. This boy, this Edward that they call the sweet rose of England, the fair herb of England, the white flower, is fabled to be handsome and brave and strong-and I am nothing. He is adored by women; they sing his praises, his looks, and his charms. I cannot even be seen at his court. I am known to nobody. I am a flower that wastes its sweetness on the desert air, indeed. He has never even seen me. No one has written a single, solitary ballad about me; no one has drawn my likeness. I am wife to a man of no ambition, who will not ride out to war until he is forced to go. I am mother to a son in my enemy’s keeping, and I am the distant love of a defeated man in exile. I spend my days-which get shorter all the time as the evenings draw in on this most miserable year-on my knees, and I pray to God to let this dark night pass, to let this cold winter pass, and to throw down the House of York and let the House of Lancaster come home.

AUTUMN 1470

It is not one dark winter, it is nearly ten winters before God releases me and my house from the misery of defeat in our days and exile in our own country. For nine long years I live with a husband with whom I share nothing but our new house at Woking in the country. House, land, and interest we share, and yet I am lonely, longing for my son, raised by my enemy whom I have to pretend is my friend. Together, Stafford and I conceive no child, which I think is the fault of the midwives at the birth of my son Henry, and I have to endure my husband’s generous acceptance that I will not give him an heir. He does not reproach me, and I have to bear his kindness as best I can. We both have to endure the power of the Yorks, who wear the ermine collar of monarchy as if they were born to it. Edward, the young king, marries a nobody in the first years of his reign, and most people think she enchanted him by witchcraft with the help of her witch mother Jacquetta, the great friend of our queen, who has turned her coat and now rules the York court. My husband’s nephew, the little duke Henry Stafford, is snatched up by the greedy siren Elizabeth, who calls herself queen. She takes him from us, his family, and betrothes him to her own sister, Katherine Woodville, a girl born and bred only to raise hens in Northampton, and so the Woodville girl becomes the new duchess and head of our house. My husband does not protest against this kidnap of our boy; he says it is part of the new world, and we have to become accustomed. But I do not. I cannot. I will never become accustomed.

Once a year I visit my boy in the ostentatious luxury of the Herbert household and see him grow taller and stronger; see him at ease in among the Yorks, beloved of Anne Devereux, the wife of Black Herbert; see him affectionate and comfortable with their son William, his dearest friend, his playmate, and his companion in his studies; and gentle with their daughter Maud, who clearly they have picked out for him as a wife, without a word to me.

Every year I visit faithfully and speak to him of his uncle Jasper in exile, and of his cousin the king imprisoned in the Tower of London, and he listens, his brown head inclined to me, his brown eyes smiling and obedient. He listens for as long as I speak, politely attentive, never disagreeing, never questioning. But I cannot tell if he truly understands even one word of my earnest sermon: that he must hold himself in waiting, that he is to know that he is a boy chosen for greatness, that I, his mother, heiress to the Beauforts and to the House of Lancaster, nearly died in giving birth to him, that the two of us were saved by God for a great purpose, that he was not born to be a boy glad of the affection of such as William Herbert. I do not want a girl like Maud Herbert as my daughter-in-law.

I tell him he must live with them like a spy; he must live with them like an enemy in their camp. He must speak politely but wait for his revenge. He must bend the knee to them but dream of the sword. But he will not. He cannot. He lives with them like an openhearted boy of five, then six, then seven; he lives with them until he is thirteen; he grows into a young man under their care, not mine. He is a boy of their making, not mine. He is like a beloved son to them. He is not a son to me, and I will never forgive them for this.

For nearly nine years I whisper poison in his little ear against the guardian that he trusts, and against his guardian’s wife that he loves. I can see him flourishing in their care, I can see him growing under their tuition. They hire masters of swordsmanship, of French, of mathematics, of rhetoric for him. They spare no fee that would teach him skills or encourage him to learn. They give him the education of their own son; the two boys study side by side as equals. I have no cause to complain. But I stifle a silent howl of resentment and anger that I can never release: that this is my boy, that this is an heir to the throne of England, that this is a boy of Lancaster-what in the name of God is he doing, flourishing and happy, in a House of York?

I know the answer to this. I know just what he is doing in one of the loyal houses of York. He is growing into a Yorkist. He loves the luxury and comfort of Raglan Castle; I swear he would prefer it to the holy plainness of my new home at Woking, if he had ever been allowed to see my home. He warms to the gentle piety of Anne Devereux; my demand that he know every collect of the day and honor every saint’s day is too much for him, I know it is. He admires the courage and dash of William Herbert, and while he loves Jasper still, and writes to tell him so, boyish letters filled with boasting and affection, he is learning to admire his uncle’s enemy and adopt him as a very model of a chivalrous, honorable knight and landlord.

And worst of all for me, he thinks of me as a woman who cannot reconcile herself to defeat; I know he thinks this. He thinks I am a woman who saw my king driven from his throne, and my husband killed and my brother-in-law run away, and he thinks that it is disappointment and failure that has made me seek solace in religion. He thinks I am a woman seeking consolation in God for the failure of her life. Nothing I can do can convince him that my life in God is my power and glory. Nothing I can do can convince him that I do not see our cause as lost, I don’t see myself as defeated, I don’t believe, not even now, that York will hold the throne. I think we will return, I think we will win. I can say this to him, I can say it over and over again; but I have no evidence to support my conviction, and the embarrassed smile, and the way he bows his head to me and murmurs, “Lady Mother, I am sure you are right,” tells me, as clearly as if he loudly contradicted me, that he thinks I am wrong and mistaken and-worse than that-irrelevant.

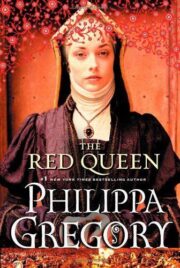

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.