“I have to go, and the longer I stay, the more danger you are in, and the more likely I am to be caught. Now that the boy is in your keeping, I can leave him with a clear conscience.”

“And you can leave me?”

He smiles his crooked smile. “Ah, Margaret, all the time I have known you, you have been the wife of another man. I am a courtly lover, as it turns out. A troubadour to a distant mistress. I don’t ask for more than a smile and to be in your prayers. I love from afar.”

“But this is going to be very far,” I say childishly.

Silently, he puts a gentle finger to my cheek and wipes away a single tear.

“How shall I live without you?” I whisper.

“I can’t do anything to dishonor you,” he says gently. “Really, Margaret, I could not. You are my brother’s widow and your son carries a great name. I have to love and serve you, and for now, I serve you best by going away and mustering an army to take your son’s lands back into my keeping, and to defeat those who would deny his house.”

The trumpet call, which announces that dinner is ready to be served, echoes up the stone well of the stair, making me jump.

“Go on,” Jasper says. “I will see you and your husband in the solar later. You can tell him I am here.”

He gives me a little push, and I start down the stairs. As I look back I see that he has gone into the nursery. I realize that he trusts Henry’s nurse with his life, and he has gone to sit beside my sleeping boy.

Jasper joins us in the solar after dinner. “I shall leave early tomorrow,” he says. “There are men here whom I can trust to take me to Tenby. I have a ship waiting there. Herbert is looking for me in the north of Wales; he can’t get here in time, even if he hears of me.”

I glance at my husband. “Can we ride with you and see you leave?” I ask.

Jasper politely waits for my husband to rule.

“As you wish,” Sir Henry says levelly. “If Jasper thinks it safe. It might help the boy to see you safely away; he is likely to pine for you.”

“It’s safe enough,” Jasper says. “I had thought Herbert was on my tail, but he has taken a false scent.”

“At dawn then,” my husband says pleasantly. He rises to his feet and puts out a hand to me. “Come, Margaret.”

I hesitate. I want to stay by the fireside with Jasper. He will go tomorrow, and we will have no time alone together at all. I wonder that my husband does not see this, does not understand that I might want some time alone with this friend of my childhood, this guardian of my son.

His weary smile would have told me-if I had been looking at him-that he understood this completely, and much more. “Come, wife,” he says gently, and at that bidding Jasper gets to his feet and bows over my hand, so I have to go to bed with my husband, and leave my dearest friend, my only friend, sitting alone over the fire for his last evening in the home that we used to share.

In the morning I see a different child in my boy Henry. His face is bright with happiness; he is his uncle’s little shadow, following him like an enthusiastic puppy. His manners are still beautiful, perhaps even better when he knows that his guardian is watching him, but there is a joy in every movement when he can look up and see Jasper’s approving smile. He serves him like a page boy, standing behind him proudly holding his gloves, stepping forwards to take the reins of the great horse. Once, he stops a groom bringing a whip: “Lord Pembroke doesn’t like that whip,” he says. “Get the one with the plaited end,” and the man bows and runs to obey.

Jasper and he walk side by side to inspect the guard who have assembled to ride with us to Tenby. Henry walks just as Jasper does, his hands clasped behind his back, his eyes intent on the faces of the men, though he has to look up as they tower above him. He stops, just as Jasper does, from time to time to remark on a well-honed weapon, or on a well-groomed horse. To see my little boy inspecting the guard, the very mirror of the great commander who is his uncle, is to watch a prince serving his apprenticeship.

“What does Jasper think his future will be?” my husband wonders in my ear. “For he is training a little tyrant here.”

“He thinks he will rule Wales as his father and grandfather did,” I say shortly. “At the very least.”

“And what at the most?”

I turn my head and I don’t answer, for I know the extent of Jasper’s ambition in the regal bearing of my son. Jasper is raising an heir to the throne of England.

“If they had weapons, or even boots, this would be a little more impressive,” my husband the Englishman remarks quietly in my ear; and for the first time I notice that many of the guard are indeed barefoot, and many of them have only sickles or coppicing hooks. They are an army of country men, not professional soldiers. Most of Jasper’s battle-hardened, well-equipped guard died under the three suns of Mortimer’s Cross, the rest of them at Towton.

Jasper reaches the end of the line of soldiers and snaps his fingers for his horse. Henry turns and nods to the groom as if to tell him to hurry. He is to ride before his uncle, and from the confident way that Jasper swings up into the big saddle and then bends down to offer Henry his hand, I can tell that they have done this often. Henry stretches up to reach Jasper’s big hand, and is hauled up to sit before him. He nestles back into his uncle’s firm grip and beams with pride.

“March on,” Jasper says quietly. “For God and the Tudors.”

I think that Henry will cry when we get to the little fishing port of Tenby and Jasper swings him down to the ground and then jumps down beside him. For a moment Jasper kneels, and his copper head and Henry’s brown curls are very close. Then Jasper straightens up and says, “Like a Tudor, eh, Henry?” and my little boy looks up to his uncle and says, “Like a Tudor, sir!” and solemnly the two of them clasp hands. Jasper claps him on the back so hard as to nearly knock him off his little feet, and then turns to me.

“Godspeed,” Jasper says to me. “I don’t like long farewells.”

“Godspeed,” I say. My voice is trembling, and I don’t dare to add more before my husband and the men of the guard.

“I’ll write,” Jasper says. “Keep the boy safe. Don’t spoil him.”

I am so irritated by Jasper telling me how to care for my own son that I can hardly speak for a moment, but then I bite my lip. “I will.”

Jasper turns to my husband. “Thank you for coming,” he says formally. “It is good to hand Henry over in safety, to a guardian I can trust.”

My husband inclines his head. “Good luck,” he says quietly. “I will keep them both safe.”

Jasper turns on his heel and is about to walk away when he checks, turns back to Henry, and sweeps him up for a quick, hard hug. When he puts the little boy gently down, I see that Jasper’s blue eyes are filled with tears. Then he takes the reins of his horse and leads it carefully and quietly onto the ramp to the boat. A dozen men go with him; the rest wait with us. I glance at their faces and see their aghast look, as their lord and commander shouts to the master of the ship that he can cast off.

They throw the lines to the ship; they raise the sail. At first it seems as if it is not moving at all, but then the sails flap and quiver and the wind and the force of the tide slides the ship from the little stone quayside. I step forwards and put my hand on my little son’s shoulder; he is trembling like a foal. He does not turn his head at my touch; he is straining his eyes to see the last possible sight of his guardian. Only when the ship is a little distant dot at sea does he take a shuddering breath and drop his head and I feel his shoulders heave with a sob.

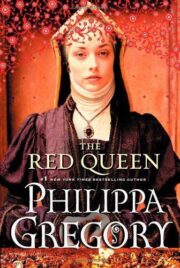

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.