I can see my husband riding the margins of the field, talking to his land steward, and I kick Arthur into a rolling canter and come up to him in a rush that makes his own horse sidle and curvet in the mud.

“Steady,” my husband says, drawing rein. “What’s the matter?”

In reply, I thrust the letter at him and wave the land steward out of earshot. “We have to fetch Henry,” I say. “Jasper will meet us at Pembroke Castle. He has to go. We have to go there.”

He is infuriatingly slow. He takes the letter and reads it, then he turns his horse’s head for home and reads it again, as he rides.

“We have to leave at once,” I say.

“As soon as it is safe to do so.”

“I must fetch my son. Jasper himself tells me to fetch him!”

“Jasper’s judgment is not of the best, as perhaps you can now see, since his cause is lost and he is running away to France or Brittany or Flanders and leaving your son without a guardian.”

“He has to!”

“Anyway, he is going. His advice is not material. I will muster a suitable guard, and if the roads are safe enough, I will go and fetch Henry.”

“You will go?” I am so anxious for my son that I forget to hide the scorn in my voice.

“Yes. I, myself. Did you think me too decrepit to ride to Wales in haste?”

“There may be soldiers on the way. William Herbert’s army will be on the road. You are likely to cross their path.”

“Then we shall have to hope that my ancient years and gray hairs protect me,” he says with a smile.

I don’t even hear the joke. “You have to get through,” I say, “or Jasper will leave my boy alone at Pembroke, and Herbert will take him.”

“I know.”

We come into the stable yard, and he has a quiet word with Graham, his master of horse, and next thing all the men-at-arms are tumbling from our house and from the stable yard, and the chapel bell is tolling to call the tenants to muster. It is all done at such speed and efficiency that for the first time I see that my husband has command of his men.

“Can I come too?” I ask. “Please, husband. He is my son. I want to bring him safely home.”

He looks thoughtful. “It will be a hard ride.”

“You know I am strong.”

“There might be danger. Graham says that there are no armies near here, but we are going to have to cross most of England and nearly all of Wales.”

“I am not afraid, and I will do as you order.”

He pauses for a moment.

“I beg you,” I say. “Husband, we have been married three and a half years, and I have never asked you for anything.”

He nods. “Oh, very well. You can come too. Go and pack your things. You can bring only a saddle bag, and tell them to put a change of clothes up for me. Tell them to pack provisions for fifty men.”

If I commanded the house, I would do it myself, but I am still served as a guest. So I get off my horse and go to the groom of the servery and tell him that his master, and I, and the guard are going on a journey and we will need food and drink. Then I tell my maid and Henry’s servant to pack a bag for us both, and I go back to the stable yard to wait.

They are ready within the hour, and my husband comes out of the house with his traveling cloak carried on his arm. “D’you have a thick cloak?” he asks me. “No, I thought not. You can have this, and I will use an old one. Take it, strap it to your saddle.”

Arthur is steady as I mount him, as if he knows that we have work to do. My husband draws up his horse beside mine. “If we see an army, then Will and his brother will ride away with you. You are to do as they order. They are commanded to ride with you for home, or for the nearest house of safety, as fast as they can. Their task is to keep you safe; you are to do as they say.”

“Not if it is our army,” I point out. “What if we meet the queen’s army on the road?”

He grimaces. “We won’t see the queen’s army,” he says shortly. “The queen could not pay for an archer, let alone a troop. We will not see her again until she can make an alliance with France.”

“Well anyway, I promise,” I say. I nod at Will and his brother. “I will go with them when you tell me I must.”

My husband nods, his face grim, and then turns his horse so he is at the head of our little guard-about fifty mounted men armed with nothing but a handful of swords and a few axes-and leads us west for Wales.

It takes us more than ten days of hard riding every day to get there. We go west on poor roads, skirting the town of Warwick and going cross-country wherever we can, for fear of meeting an army: any army, friend or foe. Every night we have to go to a village, an alehouse, or an abbey and find someone who can guide us for the next day. This is the very heart of England, and many people know no farther than their parish boundaries. My husband sends scouts a good mile ahead of us with orders that if there is any sign of outriders from any army, they are to gallop back to warn us, and we will turn off the road and get into hiding in the forest. I cannot believe that we must hide, even from our own army. We are Lancaster, but the Lancaster army that the queen has brought down on her country is out of all control. Some nights the men have to sleep in a barn while Henry and I beg hospitality in a farmhouse. Some nights we take a room at an inn on the road, one night in an abbey where they have dozens of guest rooms and are used to serving small armies of men marching from one battle to another. They don’t even ask us which lord we serve, but I see that there is no gold and silver on show in the church. They will have buried their treasures in some hiding place and are praying for peaceful times to come again.

We don’t go to the big houses nor to any of the castles that we can sometimes see on the hills overlooking the road, or sheltered by great woods. The victory of York has been so complete that we don’t dare advertise that we are riding to save my son, an heir to the House of Lancaster. I understand now what Henry my husband tried to tell me before, that the country is blighted not only by war, but by the constant threat of war. Families who have been friends and neighbors for years avoid each other in fear, and even I, riding towards land that belonged to my first husband, whose name is still beloved, am fearful of meeting anyone who might remember me.

On the road, when I am exhausted and aching in every bone in my body, I learn that Henry Stafford cares for me, without ever making a fuss over me, or suggesting that I am a weak woman and should not have come. He lifts me down from my horse when we take a rest, and he sees that I have wine and water. When we stop for dinner, he gets my food himself, even before he is served, and then he spreads out his own cloak for my bed, and covers me up and makes me rest. We are lucky with the weather, and it does not rain on our journey. He rides beside me in the mornings and teaches me the songs that the soldiers sing: bawdy songs for which he invents new words for me.

He makes me laugh with his nonsense songs, and he tells me of his own childhood, as a younger son of the great House of Stafford, and how his father meant him for the church until he begged to be excused. They would not release him from their plan until he told the priest that he feared he was possessed by the devil, and they were all so anxious about the state of his soul that they gave up the idea of the priesthood for him.

In return, I tell him how I wanted to be a saint, and how glad I was when I found I had saints’ knees, and he laughs out loud at that and puts his hand over mine on my reins, and calls me a darling child, and his very own.

I had thought him a coward when he would not go to war and when he came back so silent from the battlefield; but I was wrong. He is a very cautious man, and he believes wholeheartedly in nothing. He would not be a priest for he could not give himself wholly to God. He was glad that he was not born the oldest, for he did not want to be duke and head of such a great house. He is of the House of Lancaster, but he dislikes and fears the queen. He is enemy to the House of York, but he thinks highly of Warwick and admires the courage of the boy of York, and surrendered his sword to him. He would not dream of going into exile like Jasper; he likes his home too much. He does not align himself with any lord but thinks for himself, and I see now what he means when he says he is not a hound to yelp when the huntsman blows the horn. He considers everything in the light of what might be right, and what would be the best outcome for himself, for his family, his affinity, and even for his country. He is not a man to give himself easily. Not like Jasper. He is not a man for these times of passion and hot temper.

“A little caution.” He smiles at me as Arthur splashes stolidly through the great river crossing of the Severn, the gateway to Wales. “We have been born into difficult times, when a man or even a woman has to choose their own way, has to choose their loyalties. I think it is right to go carefully and to think before acting.”

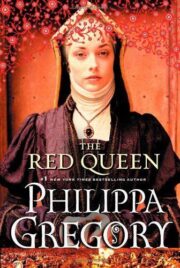

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.