Stafford staggered to his feet, horrified. “Get back! Regroup!” he shouted; but he knew that no man would listen to him, and then he heard, above the screams of the battle, the timbers of the bridge shiver and groan.

“Clear the bridge! Clear the bridge!” Stafford fought his way, pushing and shoving, towards the bank to shout at the men, still stabbing and hacking though they could all feel the bridge start to sway under the shifting load. The men cried out warnings, but they still fought, hoping to make an end and break away, and then the rails of the bridge went outwards, and the timber supports cracked, and the whole structure went down, throwing men, enemies, horses, and corpses all as one into the water.

“’Ware bridge!” Stafford shouted on the riverbank, then as the enormity of the defeat started to sink in, “’Ware bridge!” he said more softly.

For a moment, as the snow fell around him and the men in the fast-flowing water went down and came up shouting for help and were then pulled down again by the weight of their armor, it was as if everything had gone very quiet, and he was the only man alive in the world. He looked around and could not see another man standing. There were some clinging to the timbers and still hacking at each other’s grasping fingers, there were some drowning before him, or being swept away in the bloodstained flood; on the battlefield the men on the ground lay still, slowly disappearing under the falling snow.

Stafford, chilled in the cold air, felt the snow fall cleanly on his sweaty face, put out his tongue like a child, and felt the flake rest and then melt in the warmth of his mouth. Out of the whiteness another man walked slowly, like a ghost. Wearily, Stafford turned and dragged his sword from the scabbard and readied himself for another fight. He did not think he had the strength to hold up his heavy sword, but he knew he must find from somewhere the courage to kill another fellow countryman.

“Peace,” the man said in a voice drained of emotion. “Peace, friend. It’s over.”

“Who’s won?” Stafford asked. Beside them the river was rolling corpses over and over in the flood. In the field all around them men were getting to their feet or crawling to their lines. Most of them were not moving at all.

“Who cares?” the man said. “I know I have lost all my troop.”

“You are wounded?” Stafford asked as the man staggered.

The man took away his hand from his armpit. At once blood gushed out and splashed to the ground. A sword had stabbed him in the underarm joint of his armor. “I will die, I think,” he said quietly, and now Stafford saw that his face was as white as the snow on his shoulders.

“Here,” he said. “Come on. I have my horse near. We can get to Towton; we can get you strapped up.”

“I don’t know if I can make it.”

“Come on,” Stafford urged. “Let’s get out of this alive.” At once, it seemed tremendously important that one man, this one man, should survive the carnage with him.

The man leaned against him, and the two of them hobbled wearily uphill towards the Lancaster lines. The stranger hesitated, gripped his wound, and choked on a laugh.

“What is it? Come on. You can make it! What is it?”

“We’re going uphill? Your horse is on the ridge?”

“Yes, of course.”

“You’re for Lancaster?”

Stafford staggered under his weight. “Aren’t you?”

“York. You are my enemy.”

Embracing like brothers, the two men glared at each other for a moment and then both brokenly laughed.

“How would I know?” the man said. “Good God, my own brother is on the other side. I just assumed you were for York, but how could any man tell?”

Stafford shook his head. “God knows what I am, or what will happen, or what I will have to be,” he said. “And God knows that a battle like this is no way to resolve it.”

“Have you fought before in these wars?”

“Never, and if I can, I never will again.”

“You’ll have to come before King Edward and surrender yourself,” the stranger said.

“King Edward,” Stafford repeated. “That’s the first time I have heard the boy of York called king.”

“This is the new king,” the man said certainly. “And I will ask him to forgive you and release you to your home. He will be merciful, though if it were the other way round and you took me to your queen and to your prince, I swear I would not survive them. She kills unarmed prisoners-we don’t. And her son is a thing of horror.”

“Come on then,” Stafford said, and the two of them fell into line with the Lancaster soldiers waiting to beg pardon of the new king and promise never to raise arms against him again. Before them were Lancaster families that Stafford had known all his life, among them Lord Rivers and his son Anthony, their heads bowed, silent under the shame of defeat. Stafford cleaned his sword while he waited and readied himself to offer it up. It was still snowing, and the wound in his leg was throbbing as he walked slowly up to the crest of the ridge where the empty pole for the royal standard still stood at the peak with the Lancaster standard-bearers dead all around it and the York boy standing tall.

My husband does not come back from the war like a hero. He comes quietly, with no stories of battle and no tales of chivalry. Twice, three times, I ask him what it was like, thinking that it might have been like Joan’s battles: a war in the name of God for the king ordained by God, hoping that he might have seen a sign from God-like the three suns over the York victory-something that would tell us that God is with us despite the setback of defeat. But he says nothing, he will tell me nothing; he behaves as if war is not a glorious thing at all, as if it is not the working out of God’s will by ordeal.

All he will tell me, briefly, is that the king and the queen got safely away with the prince, the head of my house, Henry Beaufort, with them. They have fled to Scotland and will, no doubt, rebuild their shaken army, and that Edward of York must have the luck of the hedgerow rose of his badge, for he fought in grief and mist at Mortimer’s Cross, uphill in snow at Towton, and won both battles, and is now crowned King of England by public acclaim.

We spend the summer quietly, almost as if we are in hiding. My husband may have been pardoned for riding out against the new King of England, but no one is likely to forget that we are one of the great families of the Lancaster connection, and that I am the mother of a boy in line to the lost throne. Henry goes up to London to gather news and brings me back a beautifully copied manuscript of The Imitation of Christ in French that he thinks I might translate into English, as part of my studies. I know he is trying to keep my mind from the defeat of my house, and the despair of England, and I thank him for his consideration and start to study; but my heart is not in it.

I wait for news from Jasper, but I imagine he is lost in the same sorrow that greets me on waking, every morning, before I am even fully awake. Every day I open my eyes and realize, with such a sick pang in my heart, that my cousin the king is in exile-who knows where? – and our enemy is on his throne. I spend days on my knees, but God sends me no sign that these days are only to test us and that the true king will be restored. Then, one morning, I am in the stable yard, when a messenger comes riding in, muddy and travel-stained, on a little Welsh pony. I know at once that he brings me word, at last, from Jasper.

As usual, he is brusque.

William Herbert is to be given all of Wales, all my lands and my castles, as prize for turning his coat back to York. The new king has made him a baron also. He will hunt me down as I hunted him, and I doubt that I will get a pardon from a tender king as he did. I will have to leave Wales. Will you come and fetch your boy? I will meet you at Pembroke Castle within the month. I won’t be able to wait longer than that.

– J.

I round on the stable lad. “Where is my husband, where is Sir Henry?”

“He is riding the fields with his land steward, my lady,” the boy says.

“Saddle my horse, I must see him,” I say. They bring Arthur from his stall and he catches my impatience and tosses his head while they fiddle with the bridle, and I say: “Hurry, hurry.” As soon as he is ready, I am in the saddle and riding out towards the barley fields.

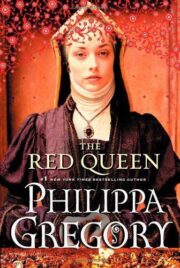

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.