I hesitate and look at my husband’s grimace. “That sounds very bad.”

“They say that the son is as vicious as the mother. All of London is for York now. Nobody wants such a boy as Prince Edward on the throne.”

“What happens next?”

He shakes his head. “It must be the last battle. The king and the queen are reunited and at the head of their army. Young Edward of York and his father’s friend Warwick are marching on them. It is no longer an argument about who should advise the king. It is now a battle about who should be king. And finally, I will have to defend my king.”

I find that I am shaking. “I never thought you would go to war,” I say, my voice trembling. “I always thought you would refuse to go. I never thought you would go to war.”

He smiles as if it is a bitter jest. “You thought me a coward, and now you cannot rejoice in my courage? Well, never mind. This is the cause that my father died for, and even he only rode out at the last possible moment. Now I find that in my turn, I will have to go. And I too have left it to the last possible moment. If we lose this battle, then we will have a York king and his heirs on the throne forever; and your house will be a royal house no more. It is not a question of the rights of the cause, but simply on which side I was born. The king must be the king; I have to ride out for that. Or your son will no longer be three steps from the throne; but a boy without a title, without lands, and without a royal name. You and I will be traitors in our own lands. Perhaps they will even give our lands to others. I don’t know what we might lose.”

“When will you go?” I ask tremulously.

His smile is without humor or warmth. “I am afraid I will have to go now.”

EASTER 1461

When they woke in the morning it was to the silence and eerie whiteness of a world of blowing snow. It was bitterly cold. The blizzard started at dawn, and the snow whirled around the standards all day. The Lancaster army, commanding the height of the long ridge near to the village of Towton, ideally placed on the heights, peered down into the valley below them, where the York army was hidden by the swirling flakes. It was too wet for the cannon to fire, and the swirling snow blinded the Lancaster archers, and their bowstrings were damp. They fired blindly, aiming in hope down the hill, into snowflakes, and time and again a volley of arrows hammered back at them as the York archers found their targets clearly silhouetted against the light sky.

It was as if God had ordered the Palm Sunday weather to make sure that it was man against man, hand-to-hand fighting, the most bitter battle of all of the battles of the war, on the field they called Bloody Meadow. Rank after rank of conscripted Lancaster soldiers dropped beneath the storm of arrows, before their commanders allowed them to charge. Then they dropped their useless bows and drew their swords, axes, and blades, and they thundered down the hill to meet the army of the eighteen-year-old boy who would be king, trying to hold his men steady against the shock of the downhill charge.

With a roar of “York!” and “Warwick! À Warwick!” they pushed forwards, and the two armies struck and held. For two long hours, while the snow churned into red slush under their feet, they locked together like a plow grinding through rocky ground. Henry Stafford, riding his horse downhill into the thick of it, felt a stab to his leg and felt his horse stagger and fall beneath him. He flung himself clear but found himself lying across a dying man, his eyes staring, his bloody mouth mumbling for help. Stafford pushed himself up and away, ducked down to avoid a swing from a battle-axe, and forced himself to stand and draw his sword.

Nothing in the jousting ring or the cockfighting pit could have prepared him for the savagery of this battlefield. Cousin against cousin, blinded by snow and maddened with the killing rage, the strongest of men stabbed and clubbed, kicked and stamped on fallen enemies, and the weaker men tore themselves away and started to run, stumbling and falling in heavy armor, often with a chain-mailed rider coming behind them, mace swinging to smash off their heads.

All day, in snow that whirled around them like feathers in a poultry shop, the two armies thrust and stabbed and pushed one another, going nowhere, without hope of victory, as if they were trapped inside a nightmare of pointless rage. A man falling was replaced by a reserve who would step on his body to reach up for a killer stab. Only when it started to grow dark, in the eerie white-skied twilight of spring snow, did the Lancastrian front rank started to yield ground. The first falling back was pressed hard, and they dropped back again, until those at the sides felt their fear rise greater than their rage and one by one started to break away.

At once, they gained relief, for the York men also disengaged and stepped back. Stafford, sensing a lull in the battle, rested for a moment on his sword and looked around him.

He could see the front line of the Lancaster army starting to peel away, like unwilling haymakers, heading early for home. “Hi!” he shouted. “Stand. Stand for Stafford! Stand for the king!” but their pace only quickened, and they did not look back.

“My horse,” he shouted. He knew that he must get after them and halt their retreat before they started to run in earnest. He slipped his dirty sword into its scabbard and started a stumbling run towards his horse lines, and as he ran he glanced to his right and then froze in horror.

The Yorks had not dropped back for a breath and a rest, as so often happened in battle, but had broken from the fight to run as fast as they could to their own horse lines to get their horses, and the men who had been on foot, savagely pressing the Lancaster men-at-arms, were now mounted and riding down on them, maces swinging, broadswords out, lances pointed down at throat height. Stafford leaped over a dying horse and threw himself facedown on the ground behind it as the whistle of the ball of a mace swung through the air just where his head had been. He heard a grunt of fear and knew his own voice. He heard a thunder of hooves, a cavalry charge coming towards him, and he felt himself contract like a frightened snail against the belly of the groaning horse. Above him, a rider jumped the horse and man in one leap, and Stafford saw the hooves beside his face, felt the wind as they went over, flinched against the splash of mud and snow, clung to the dying horse without pride.

When the thunder of the first rush of cavalry was past him, cautiously he raised his head. The York knights were like huntsmen, riding down the Lancaster men-at-arms who were running like deer towards the bridge over Cock Beck, the little river at the side of the meadow, their only escape. The York foot soldiers, cheering on the riders, raced beside them to head off the running enemy, before they could reach the bridge. In moments, the bridge became a mass of struggling, fighting men, Lancastrians desperate to get across and away, York soldiers pulling them back, or stabbing them in the back as they scrambled over their fallen comrades. The bridge creaked as the soldiers surged back and forth, the horses pushing onwards, forcing men over the guard rails into the freezing river, trampling the others underfoot. Dozens of men seeing the knights coming on with their great double-edged swords swinging like scythes on either side of their horses’ heads, seeing the warhorses rear up and bring down their great iron-shod hooves on men’s heads, simply jumped into the river, where soldiers were still struggling, some thrashing against the weight of their armor, others locked on each other’s heads and shoulders, forcing them down to drown in the icy, reddened waters.

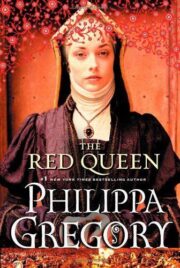

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.