“They are cowards,” I whisper to the statue of Our Lady in my private chapel. “And You punished them with shame. I prayed that they would be defeated, and You have answered my prayers and brought them low.”

When I rise from my knees, I walk out from the chapel a little taller, knowing that my house is blessed by God, is led by a man as much a saint as a king, and that our cause is just and has been won without so much as an arrow being loosed.

SPRING 1460

“Except that it is not won,” my husband observes acidly. “There is no settlement with York nor answer to his grievances. Salisbury, Warwick, and the two older York boys are in Calais, and they won’t be wasting their time there. York has fled to Ireland and he too will be gathering his forces. The queen has insisted that they all be arraigned as traitors, and now she is demanding lists of every able-bodied man in every county of England. She thinks she has the right to summon them directly to her army.”

“Surely, she means only to ask the lords to call up their own men as usual?”

He shakes his head. “No, she is going to raise troops in the French way. She thinks to command the commons directly. Her plan is to have lists of young men in every county and raise them herself, to her standard, as if she were a king in France. No one will stand for it. The commons will refuse to go out for her-why should they, she’s not their liege lord-and the lords will see it as an act against them, undermining their power. They will suspect her of going behind their backs to their own tenants. Everyone will see this as bringing French tyranny to England. She will make enemies from her natural allies. God knows, she makes it hard to be loyal to the king.”

I take his gloomy predictions to confession and tell the priest that I have to confess the sin of doubting my husband’s judgment. A careful man, he is too discreet to inquire about my doubts-after all, it is my husband who owns the chapel and the living and pays for the chantries and masses in the church; but he gives me ten Hail Marys and an hour on my knees in remorseful prayer. I kneel, but I cannot be remorseful. I am starting to fear that my husband is worse than a coward. I am starting to fear the very worst of him: that he has sympathies with the York cause. I am beginning to doubt his loyalty to the king. My rosary beads are still in my hand when I acknowledge this thought to myself. What can I do? What should I do? How should I live if I am married to a traitor? If he is not loyal to our king and our house, how can I be loyal to him as a wife? Could it be possible that God is calling me to leave my husband? And where would God want me to go, but to a man who is heart and soul loyal to the cause? Would God want me to go to Jasper?

Then, in July, everything my husband had warned about the Calais garrison becomes terribly true, as York launches a fleet, lands in Sandwich, halfway to London, and marches on the capital city, without a shot being fired against him, without a door slammed shut. God forgive the men of London, they fling open the gates for him and he marches in to acclaim, as if he is freeing the city from a usurper. The king and the court are at Coventry, but as soon as they hear the news, the call goes out across the country that the king is mustering and summoning all his affinity. York has taken London; Lancaster must march.

“Are you going now?” I demand of my husband, finding him in the stable yard, checking over the harness and saddles of his horses and men. At last, I think, he sees the danger to the king and knows he must defend him.

“No,” he replies shortly. “Though my father is there, God keep him safe in this madness.”

“Will you not even go to be with your father in danger?”

“No,” he says again. “I love my father, and I will join him if he orders me; but he has not commanded me to his side. He will unfurl the standard of Buckingham; he doesn’t want me under it, yet.”

I know that my anger flares in my face, and I meet his glance with hard eyes. “How can you bear not to be there?”

“I doubt the cause,” he says frankly. “If the king wants to retake London from the Duke of York, I imagine he only has to go to the city and discuss terms. He does not need to attack his own capital; he has only to agree to speak with them.”

“He should cut York down like a traitor, and you should be there!” I say hotly.

He sighs. “You are very quick to send me into danger, wife,” he remarks with a wry smile. “I must say, I would find it more agreeable if you were begging me to stay home.”

“I beg you only to do your duty,” I say proudly. “If I were a man, I would ride out for the king. If I were a man, I would be at his side now.”

“You would be a very Joan of Arc, I am sure,” he says quietly. “But I have seen battles and I know what they cost, and right now, I see it as my duty to keep these lands and our people in safety and peace while other men scramble for their own ambition and tear this country apart.”

I am so furious I cannot speak, and I turn on my heel and walk away to the loose box, where Arthur, the old warhorse, is stabled. Gently he brings his big head down to me, and I pat his neck and rub behind his ears and whisper that he and I should go together, ride to Coventry, find Jasper, who is certain to be there, and fight for the king.

JULY 10, 1460

Even if Arthur and I had ridden out, we would have got there too late. The king had his army dug in outside Northampton, a palisade of sharpened stakes before them to bring down the cavalry, their newly forged cannon primed and ready to fire. The Yorks, led by the boy Edward, Earl of March, the traitors Lord Fauconberg and Warwick himself in the center, came on in three troops in the pouring rain. The ground churned into mud under the horses’ hooves, and the cavalry charge got bogged down. God rained down on the rebels, and they looked likely to sink in the quagmire. The boy Edward of York had to dig deep to find the courage to lead his men through ground that was a marsh, against a hail of Lancaster arrows. He would surely have failed and his young face would have gone down in the mud; but the leader on our right, Lord Grey of Ruthin, turned traitor in that moment, and pulled the York forces up over the barricade and turned on his own house in bitter hand-to-hand fighting, which pushed our men back toward the River Nene, where many drowned, and let Warwick and Fauconberg come on.

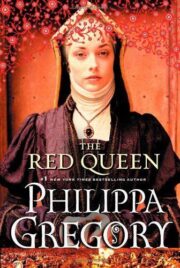

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.