But the York army played a trick, a trick that Salisbury could play since his men would do anything for him-fall back, stand, attack-so he commanded them to withdraw, as if giving up the fight. Our cavalry rode them down, thinking they were chasing a runaway force, and found that they were the ones who were caught, just as they were wading through the brook. The enemy turned and stood, fast as a striking snake, and our men had to fight their way uphill through ground that became more and more churned as they tried to charge the horses through it and drag our guns upwards. The York archers could shoot downhill into our men, and their horses died under them, and they were lost in the mud and the mess and the hail of arrows and shot. John said that the river was red with blood of the wounded and the dying, and men who waded through to escape the battle were dyed red.

Night fell on a battlefield where we had lost the cause, and our men were left in the fields to die. The York commander Salisbury slipped away before the main body of our army could come up, and deceitfully left his cannon in the field and paid some turncoat friar to shoot them off all night. When the royal army thundered up at dawn, ready for battle, expecting to find the Yorks standing on the defensive with their cannon, ready to massacre the traitors, there was no one there but one drunken hedge friar, hopping from firing pan to firing pan, who told them that their enemy had run off to Ludlow, laughing about their victory over the two Lancaster lords.

“So, battle has been met,” my husband says grimly. “And lost.”

“They didn’t engage the king himself,” I say. “The king would have won, without a doubt. They just met two of our lords, not the king in command.”

“Actually, they faced nothing more than one threadbare friar,” my husband points out.

“Our two lords would surely have won if the forces of York had fought fairly,” I insist.

“Yes, but one of those lords is now dead, and the other is captured. I think we can take it that our enemies have won the first round.”

“But there will be more fighting? We can regroup? When Joan failed to take Paris she didn’t surrender-”

“Ah, Joan,” he says wearily. “Yes, if we take Joan as our example, we should go on to the death. A successful martyrdom beckons. You are right. There will be more battles. You can be sure of that. There are now two powers marching around each other like cocks in a pit, seeking advantage. You can be sure that there will be a fight, and then another, and then another, until one or the other is sickened by defeat or dead.”

I am deaf to his scathing tone. “Husband, will you go now to serve your king? Now that the first battle has been fought, and we have lost. Now that you can see that you are badly needed. That every man of honor has to go.”

He looks at me. “When I have to go, I will,” he says grimly. “Not before.”

“Every true man in England will be there but you!” I protest hotly.

“Then there will be so many true men that they won’t need a faintheart like me,” says Sir Henry, and walks from the sick chamber, where Jasper’s volunteer is dying, before I can say more.

There is coldness between Sir Henry and me after this, and so I don’t tell him when I receive a crumpled piece of paper from Jasper with his spiky ill-formed writing that says simply:

Don’t fear. The king himself is taking the field. We are marching on them

– J.

Instead, I wait till we are alone after dinner and my husband is fingering a lute without making a tune, and I ask: “Have you any news from your father? Is he with the king?”

“They are chasing the Yorks back to their castle at Ludlow,” he says, picking out a desultory little melody. “My father says there are more than twenty thousand turned out for the king. It seems that most men think that we will win, that York will be captured and killed, though the king in his tender heart has said he will forgive them all if they will surrender.”

“Will there be another battle?”

“Unless York decides he cannot face the king in person. It is one sort of sin to kill your friends and cousins, quite another to order your bowmen to fire at the king’s banner and him beneath it. What if the king is killed in battle? What if York brings his broadsword down on the king’s sanctified head?”

I close my eyes in horror at the thought of the king, all but a saint, being martyred by his own subject who has sworn loyalty to him. “Surely, the Duke of York cannot do it? Surely, he cannot even consider it?”

OCTOBER 1459

As it turned out, he could not.

When the army of York came face-to-face with their true king on the battlefield, they found that they could not bring themselves to attack him. I was on my knees for all of the day that the York forces drew up behind their guns and carts and looked down the hill to Ludford Bridge and the king’s own banners. They spent the day parlaying, as I spent the day wrestling with my prayers, and in the night, their sinful courage collapsed beneath them and they ran away. They ran like the cowards they were, and in the morning the king, a saint, but thank God not a martyr, went among the ranks of the York common soldiers, abandoned in their lines by their commanders, and forgave them and kindly sent them home. York’s wife, the Duchess Cecily, had to wait before the town cross in Ludlow as the king’s mob poured in, hungry for plunder, the keys to the castle in her hand, her two little boys George and Richard trembling on either side of her. She had to surrender to the king and take her boys into imprisonment, not knowing where her husband and two older sons had fled. She must have been shamed to her soul. The great rebellion of the House of York and Warwick against their divinely appointed king was ended in a brawl of looting in York’s own castle, and with their duchess in prison clutching her little traitorous boys who wept for their defeat.

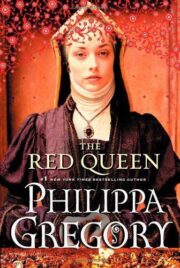

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.