He gives me much freedom in our life together, allowing me to attend chapel as often as I wish; I command the priest and the church that adjoins our house. I have ordered the services to run to the daily order of a monastery, and I attend most of them, even the offices of the night on holy days, and he makes no objection. He gives me a generous allowance and encourages me to buy books. I am starting to create my own library of translations and manuscripts, and occasionally he sits with me in the evenings and reads to me from the gospel in Latin, and I follow the words in an English translation that he has had copied for me, which I am slowly coming to understand. In short, this man treats me more as his young ward than his wife, and provides for my health, my education, and my religious life.

He is kind and considerate for my comfort; he makes no complaint that a baby has not yet been conceived, and he does his duty gently.

And so, waiting for Jasper, I feel strangely ashamed, as if I have found a safe haven and ignobly run away from the danger and fears of Wales. Then I can see the cloud of dust on the road, hear the hoofbeats and the clatter of the arms, and Jasper and his men rattle into the stable yard. He is with fifty mounted horsemen, all of them carrying weapons, all of them grim-faced as if ready for a war. Sir Henry is at my side as we step forwards to greet Jasper, and any hope that I had that he might have taken my hand, or kissed my lips, vanishes when I see that Sir Henry and Jasper are anxious to talk to each other, and neither of them need me there at all. Sir Henry grasps Jasper’s elbows in a hard embrace. “Any trouble on the road?”

Jasper slaps him on the back. “A band of brigands wearing the white rose of York but nothing more,” he says. “We had to fight them off, and then they ran. What’s the news around here?”

Sir Henry grimaces. “The county of Lincolnshire is mostly for York; Hertfordshire, Essex; and East Anglia for him or for his ally Warwick. South of London, Kent is half rebel as usual. They suffer so much from the French pirates and the blockade of trade that they see the Earl of Warwick in Calais as their savior and they will never forgive the French queen for her birth.”

“Will I get to London unscathed, d’you think? I want to go the day after tomorrow. Are there many armed bands raiding the highway? Should I ride cross-country?”

“As long as Warwick stays in Calais, you will only face the usual rogues. But they say he could land at any time, and then he would march to meet York at Ludlow, and your paths could cross on the way. Better send scouts ahead of you and keep a party following behind. If you meet Warwick, you will find yourself pitched into battle, perhaps the first of a war. Are you going to the king?”

They turn and walk into the house together, and I follow, the mistress of the house only in name. Sir Henry’s household servants always have everything prepared. I am little more than a guest.

“No, the king has gone to Coventry, God bless and keep him, and he will summon the York lords to meet with him there and acknowledge his rule. It is their test. If they refuse to go, then they will be indicted. The queen and the prince are with the king for their own safety. I am commanded to invest Westminster Palace and hold London for the king. I am to be ready for a siege. We are preparing for war.”

“You’ll get no help from the merchants and the City lords,” my husband warns him. “They are all for York. They cannot do business while the king cannot keep the peace, and that’s all they think of.”

Jasper nods. “That’s what I heard. I will overrule them. I am ordered to recruit men and build ditches. I will turn London into a walled town for Lancaster, whatever the citizens want.”

Sir Henry takes Jasper into an inner room; I follow, and we close the door behind us so that they can speak privately. “There are few in the whole country who could deny that York has just cause,” my husband says. “You know him yourself. He is loyal to the king, heart and soul. But while the king is ruled by the queen and while she conspires with the Duke of Somerset, there will be no peace and no safety for York nor any of his affinity.” He hesitates. “No peace for any of us in truth,” he adds. “What Englishman can feel safe if a French queen commands everything? Will she not hand us over to the French?”

Jasper shakes his head. “But still she is Queen of England,” he says flatly. “And mother to the Prince of Wales. And the chief lady of the House of Lancaster, our house. She commands our loyalty. She is our queen, whatever her birth, whatever friends she keeps, whatever she commands.”

Sir Henry smiles his crooked smile, which I know, from a year of his company, means that something strikes him as overly simple. “Even so, she should not rule the king,” he says. “She should not advise him instead of his council. He should consult York and Warwick. They are the greatest men of his kingdom; they are leaders of men. They must advise him.”

“We can deal with the membership of the royal council when the threat from York is over,” Jasper says impatiently. “There is no time to discuss it now. Are you arming your tenants?”

“I?”

Jasper shoots a shocked look at me. “Yes, Sir Henry, you. The king is calling on all his loyal subjects to prepare for war. I am recruiting men. I have come here for your tenants. Are you coming with me to defend London? Or will you march to join your king at Coventry?”

“Neither,” my husband says quietly. “My father is calling up his men, and my brother will ride with him. They will muster a small army for the king, and I would think that is enough from one family. If my father orders me to accompany him, I will go, of course. It would be my duty as his son. If York’s men come here, I will fight them, as I would fight anyone marching over my fields. If Warwick tries to ride roughshod over my land, I will defend it; but I won’t be riding out this month on my own account.”

Jasper looks away, and I blush with shame to have a husband who stays by the fireside when the call to battle is heard. “I am sorry to learn it,” Jasper says shortly. “I took you for a loyal Lancastrian. I would not have thought this of you.”

My husband glances towards me with a little smile. “I am afraid my wife also thinks the less of me, but I cannot, in conscience, go out and kill my own countrymen to defend the right of a young, foolish Frenchwoman to give her husband bad advice. The king needs the best of men to advise him, and York and Warwick are the best of men, proven true. If he makes them into his enemies, then York and Warwick may march against him, but I am sure that they intend to do no more than force the king to listen to them. I am certain they will do nothing more than insist on being in his council and having their voices heard. And since I think that is their right, how can I, in conscience, fight against them? Their cause is just. They have the right to advise him, and the queen has not. You know that as well as I.”

Jasper leaps to his feet in a swift, impatient movement. “Sir Henry, in honor, you have no choice. You must fight because your king has called on you, because the head of your house has called on you. If you are of the House of Lancaster, you follow the call.”

“I am not a hound to yelp at the hunting horn,” my husband says quietly, not at all stirred by Jasper’s raised voice. “I don’t give tongue to order. I don’t bay for the chase. I will go to war should there ever be a cause I think worth dying for-and not before. But I do admire your, er … martial spirit.”

Jasper flushes to the roots of his ginger hair at the older man’s tone. “I think this is no laughing matter, sir. I have been fighting for my king and for my house for two years, and I must remind you that it has cost me dear. I lost my own brother at the walls of Carmarthen, the heir to our name, the flower of our house, Margaret’s husband who never saw his son-”

“I know, I know, and I am not laughing. I too have lost a brother, remember. These battles are a tragedy for England, no laughing matter. Come, let us go in to dine and forget our differences. I pray that it will not come to a fight, and so must you. We need peace in England if we are to grow strong and rich again. We conquered France because the people were divided among themselves. Let us not lose our way, as they did; let us not be our own worst enemies in our own country.”

Jasper would argue; but my husband takes him by his arm and leads him to the great hall, where the men are already seated, ten to a table, waiting for their dinners. When Jasper comes in, his men hammer the table with the hilts of their daggers as applause, and I think it a great thing that he is such a commander, and so beloved of his men. He is like a knight errant from the stories; he is their hero. My husband’s servants and retainers merely bow their heads and doff their caps in silent respect as he goes by. But no one has ever cheered Henry Stafford to the rafters. No one ever will.

We walk through the deep rumble of male noise to the high table, and I see Jasper glance over at me as if he pities me for marrying a man who will not fight for his family. I keep my eyes down. I think that everyone knows I am the daughter of a coward, and now I am the wife of a coward, and I have to live with shame.

As the server of the ewery pours water over our hands and pats them with the napkin, my husband says kindly, “But I have distracted you from the great interest for my wife: the health of her son. How is young Henry? Is he well?”

Jasper turns to me. “He is well and strong. I wrote you that his back teeth were coming through; they gave him a fever for a few days, but he is through that now. He is walking and running. He is speaking a lot, not always clearly, but he chatters all the day. His nursemaid says that he is willful, but no more than befits his position in the world and his age. I have told her not to be too severe with him. He is Earl of Richmond: he should not have his spirit broken, he has a right to his pride.”

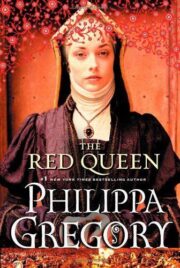

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.