“But he is well now, surely? And the court is back in London. The queen is living with the king again, and you hold Wales for him. He may stay well, their son is strong, they might have another child. Surely the Yorks will settle themselves to live as great men, under a greater king. They must know that this is their place?”

He shakes his head and spoons himself another bowl of stewed beef and a slice of manchet bread. He is hungry; he has been riding with his men for weeks. “Truly, Margaret, I don’t think the Yorks can settle. They see the king, they do their best sometimes to work with him; but even when he is well he is weak, and when he is ill, he is entranced. If I were not his man, bound heart and soul, I would find it hard to be loyal to him. I would be filled with doubt as to what comes next. I cannot in my heart blame them for hoping to control what comes next. I never doubt Richard of York. I think he knows and loves the king, and knows that he is of the royal line but not a king ordained. But Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, I would trust no further than I could see an arrow flight. He is so accustomed to ruling all the north, he will never see why he cannot rule a kingdom. Both of them, thank God, would never touch an ordained king. But every time the king is ill it leaves the question: When will he get better? And what shall we do until he is better? And the question nobody asks out loud: What shall we do if he never gets better at all?

“Worst of all is that we have a queen who is a law to herself. When the king is gone, we are a ship without a tiller and the queen is the wind that can blow in any direction. If I believed that Joan of Arc was not a holy girl but a witch, as some say, I would think she had cursed us with a king whose first loyalty is to his dreams and a queen whose first loyalty is to France.”

“Don’t say it! Don’t say it!” I object to the slight on Joan and put my hand quickly on his, to silence him. For a moment we are hand-clasped, and then gently he moves his hand from under mine, as if I may not even touch him, not even like this, like sister and brother.

“I speak to you now, trusting that it all goes no further than your prayers,” he said. “But when you are married, this January, I will talk to you only of family business.”

I am hurt that he should take his hand from my touch. “Jasper,” I say quietly. “From this January, I will have nobody in the world who loves me.”

“I will love you,” he says quietly. “As a brother, as a friend, as the guardian of your son. And you can always write to me and I can always reply to you, as a brother and a friend and the guardian of your son.”

“But who will talk to me? Who will see me as I am?”

He shrugs. “Some of us are born to a solitary life,” he says. “You will be married, but you may be very much alone. I shall think of you: you in your grand house in Lincolnshire with Henry Stafford, while I live here without you. The castle will seem very quiet and very strange without you here. The stone stairs and the chapel will miss your footstep, the gateway will miss your laughter, and the wall will miss your shadow.”

“But you will keep my son,” I say, jealous as always.

He nods. “I will keep him, even though Edmund and you are lost from me.”

JANUARY 1458

True to their word, my mother, Sir Henry Stafford, and the Duke of Buckingham come to Pembroke Castle in January, despite snow and freezing fog, to fetch me for my wedding. Jasper and I are beside ourselves trying to get in enough wood for big fires in every chamber, and to wrest enough meat from a hungry winter countryside to prepare a wedding feast. In the end we have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that there can be no more than three meat dishes and two sweetmeat courses, and that there are very few crystallized fruits and only a few marchpane dishes. It won’t be what the duke expects; but this is Wales in midwinter, and Jasper and I are united by a sort of rebellious pride that we have done what we can, and if it is not good enough for His Grace and my mother, then they can ride back to London where the Burgundian merchants arrive with a new luxury every day for those rich and vain enough to waste their money.

In the end they hardly notice the poor fare for they stay for only two days. They have brought me a fur hood and gloves for the journey, and my mother agrees that I can ride Arthur for some of the way. We are to leave early in the morning, to catch as much as we can of the short winter daylight, and I have to be ready and waiting in the stable yard so as not to disoblige my new family and my silent husband-to-be. They will take me first to my mother’s house for our wedding, and then my new husband will take me to his house at Bourne in Lincolnshire, wherever that is. Another husband, another new house, another new country, but I never belong anywhere and I never own anything in my own right.

When everything is ready, I run back upstairs and Jasper comes with me to the nursery for me to say good-bye to my son. Henry has grown out of his swaddling bands and even out of his cradle. He now sleeps in a little bed with high bars on either side. He is so near to walking alone that I cannot bear to leave him. He can stand, endearingly bowlegged, clinging onto a prayer seat or a low stool, then he eyes the next safe haven and flings himself towards it, taking one staggering step and collapsing on the way. If I am ready to play with him, he will take my hands and, with me bent double to support him, walk the length of the room and back again. When Jasper comes into the nursery, Henry crows like a cockerel, for he knows that Jasper will go up and down, and up and down, like an obedient beast turning the threshing wheel, tirelessly holding Henry’s little hands, while he pit-pats forwards on his fat little feet.

But the magic moment when he walks alone has not yet happened, and I was praying he would do it before I have to leave. Now he will take his first step without me. And every step thereafter, I know. Every step of his life, and me not there to see him walk.

“I will write to you the moment he does it,” Jasper swears to me.

“And write to me if you can make him eat meat,” I say. “He can’t live his life on gruel.”

“And his teeth,” he promises me. “I will write you as each new one comes in.”

I pull at his arm, and he turns towards me. “And if he is ill,” I whisper, “they will tell you to spare me worry. But it won’t spare me worry if I think he is ill but nobody would tell me. Swear you will write to me if he is ill at all, or if he has a fall or any sort of accident.”

“I swear,” he says. “And I will keep him as safe as I can.”

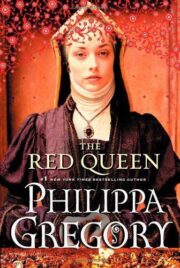

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.