“Whereas they will never call for me, and I won’t be fit for anything but to be a wife, if I am even alive,” I say irritably.

Jasper looks at me and does not laugh. He looks at me and it is as if, for the first time in my life, someone has seen me and understood me. “You are the heir whose bloodline gives Henry his claim to the throne,” he says. “You, Margaret Beaufort. And you are precious to God. You know that, at least. I have never known a woman more devout. You are more like an angel than a girl.”

I glow, the way a lesser woman would blush if someone praised her beauty. “I didn’t know you had even noticed.”

“I have, and I think you have a real calling. I know that you can’t be an abbess, of course not. But I do think you have a calling to God.”

“Yes, but Jasper, what good is it being devout, if I am not to be an example to the world? If all that they will allow for me is a marriage to someone who hardly cares for me at all, and then an early death in childbed?”

“These are dangerous and difficult times,” he says thoughtfully, “and it is hard to know what one should do. I thought that my duty was to be a good second to my brother, and to hold Wales for King Henry. But now my brother is dead, it is a constant battle to hold Wales for the king, and when I go to court the queen herself tells me that I should be commanded by her and not by the king. She tells me that the only safety for England is to follow her and she will lead us to peace and alliance with France, our great enemy.”

“So how do you know what to do?” I ask. “Does God tell you?” I think it most unlikely that God would speak to Jasper, whose skin is so very freckled, even now in March.

He laughs. “No. God does not speak to me, so I try to keep the faith with my family, with my king, and with my country in that order. And I prepare for trouble and hope for the best.”

I draw close to speak to him quietly. “Do you think that Richard of York would dare to take the king’s throne, if the king were to be ill for very long?” I ask. “If he does not get better?”

He looks bleak. “I would think it a certainty.”

“So what am I to do if I am far from you and a false king takes the throne?”

Jasper looks consideringly at the baby. “Say that our King Henry dies and then the prince, his son.”

“God forbid.”

“Amen. Say that they die the one after the other. On that day this baby is the next in line to the throne.”

“I know that well enough.”

“Do you not think that this might be your calling? To keep this child safe, to teach him the ways of kingship, to prepare him for the highest task in the land-to see him ordained as king and take the holy oil on his breast and become more than a man, a king, a being almost divine?”

“I dreamed of it,” I tell him very quietly. “When he was first conceived. I dreamed that to carry him and give birth to him was my vocation, as to bring the French king to Rheims was Joan’s. But I have never spoken of it to anyone but God.”

“Say you were right,” Jasper goes on, his whisper binding a spell around us both. “Say that my brother did not die in vain, for his death made this boy the Earl of Richmond. His seed made this boy a Tudor and so half nephew to the King of England. Your carrying him made him a Beaufort and next in direct line to the King of England. Say this is your destiny, to go through these difficult times and bring this boy to the throne. Do you not think this? Do you not feel it?”

“I don’t know,” I say hesitantly. “I thought I would have a higher calling than this. I thought I would be a mother superior.”

“There is no more superior mother in the world,” he said, smiling at me. “You could be the mother of the King of England.”

“What would they call me?”

“What?” He is distracted by my question.

“What would they call me if my son was King of England but I was not crowned as a queen?”

He thinks. “They would probably call you ‘Your Grace.’ Your son would make your husband a duke, perhaps? Then you would be ‘Your Grace.’”

“My husband would be a duke?”

“It’s the only way you could be a duchess. As a woman you could hold no title in your own right, I don’t think.”

I shake my head. “Why should my husband be ennobled, when it will be me who has done all the work?”

Jasper chokes back a laugh. “What title would you have?”

I think for a moment. “Everyone can call me ‘My Lady, the King’s Mother,’” I decide. “They can call me ‘My Lady, the King’s Mother,’ and I shall sign my letters ‘Margaret R.’”

“‘Margaret R’? You would sign yourself ‘Margaret Regina’? You would call yourself a queen?”

“Why not?” I demand. “I shall be the mother of a king. I shall be all but Queen of England.”

He bows with mock ceremony. “You shall be My Lady, the King’s Mother, and everyone will have to do whatever you say.”

SUMMER 1457

We do not speak of my destiny again, nor of the future of England. Jasper is too busy. He is gone from the castle for weeks and weeks at a time. In the early summer he comes back with his force in tatters and his own face bruised, but smiling. He rode down and captured William Herbert; the peace of Wales is restored; and the rule of Wales is again in our hands. Wales is held by a Tudor for the House of Lancaster, once more.

Jasper sends Herbert to London as a proclaimed traitor, and we hear that he is tried for treason and held in the Tower. I shudder at that, thinking of my old guardian, William de la Pole, who had been in the Tower when I, a little girl, had been forced to declare myself free of him.

“It doesn’t matter,” Jasper tells me, hardly able to speak for yawning over dinner. “Forgive me, sister, I am exhausted. I shall sleep for all of tomorrow. Herbert won’t go to the block as he deserves. The queen herself warned me that the king will pardon and release Herbert, and he will live to attack us again. Mark my words. Our king is an expert at forgiveness. He will forgive the man who raises a sword against him. He will forgive the man who raises England against him. Herbert will be released, and in time he will come back to Wales, and he and I will fight all over again for the same handful of castles. The king forgives the Yorks and thinks they will live with him in charity. This is a mark of his greatness, really, Margaret-you strive for sainthood and it must run in your family, for I think he has it. He is filled with the greatest of kindness and the greatest of trust. He cannot bear a grudge; he sees every man as a sinner striving to be good, and he does what he can to help him. You cannot help but love and admire him. It is a mark of his enemies that they take his mercy as a license to go on as they wish.” He pauses. “He is a great man, but perhaps not a great king. He is beyond us all. It just makes it very hard for the rest of us. And the common people only see weakness where there is greatness of spirit.”

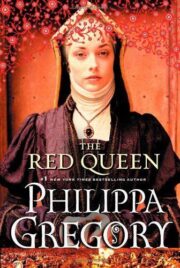

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.