She does not even blink. “The baby should always be saved in preference to the mother. That is the advice of the Holy Church, you know that. I was only reminding the women of their duty. There is no need to make everything so personal, Margaret. You make everything into your own tragedy.”

“I think it is my tragedy, if you are telling my midwives to let me die!”

She all but shrugs as she steps back. “These are the chances that a woman faces. Men die in battle; women die in childbirth. Battle is more dangerous. The odds are with you.”

“But what if the odds are against me, if I am unlucky? What if I die?”

“Then you will have the satisfaction of knowing that you made at least one son for the House of Lancaster.”

“Mother, before God,” I say, my voice shaking with tears, “I swear that I have to believe that there is more for me in life than being wife to one man after another, and hoping not to die in childbirth!”

She shakes her head, smiling at me as if my sense of outrage is like a little girl shouting over her toys. “No, truly, my dear, there is nothing more for you,” she says. “So do your duty with an obedient heart. I will see you in January, at your wedding.”

I ride back to Pembroke Castle in a surly silence, and none of the signs of the coming spring down the greening lanes give me any pleasure at all. I turn my head away from the wild daffodils that make the high meadows a blaze of silver and gold, and I am deaf to the insistent, joyous singing of the birds. The lapwing soaring blunt-winged over a plowed field and calling out his sharp whistle means nothing to me, for everything means nothing to me. The snipe diving downwards making a sound like a roll of drums does not call to me. My life will not be dedicated to God, will not be special in any way. I shall sign myself Margaret Stafford-I won’t even be duchess. I shall live like a hedge sparrow on a twig until the sparrowhawk kills me, and my death will be unnoticed and unmourned by any. My mother herself has told me that there is nothing in my life that is worth doing, and the best I can hope is to avoid an early death in childbirth.

Jasper spurs on ahead as soon as he sees the high towers of Pembroke, and so greets me at the castle gates with my baby in his arms, beaming with joy. “He can smile!” he exclaims before the horses even come to a standstill. “He can smile. I saw it. I leaned over his cradle to pick him up, and he saw me, and he smiled. I am sure it was a smile. I did not think he would smile so early. But it was a smile for sure. Perhaps he will smile at you.”

We both wait expectantly, looking into the dark blue eyes of the little baby. He is still strapped up as if ready for the coffin; only his eyes can move, he cannot even turn his head. He is swaddled into immobility.

“Perhaps he will smile later,” Jasper says consolingly. “There! Did he then? No.”

“It doesn’t matter, since I am to leave him within a year anyway, since I have to go and marry Sir Henry Stafford. Since I now have to give birth to Stafford boys, even if I die in the trying. Perhaps he has nothing to smile about; perhaps he knows he is to be an orphan.”

Jasper turns with me towards the front door of the castle, walking beside me, my baby resting comfortably in his arms. “They will let you visit him,” he says consolingly.

“But you are to keep him. I suppose you knew. I suppose you all planned this together. You, and my mother, and my father-in-law, and my old husband-to-be.”

He glances down at my tearful face. “He is a Tudor,” he says carefully. “My brother’s son. The only heir to our name. You could choose no one better to care for him than me.”

“You are not even his father,” I say irritably. “Why should he stay with you and not with me?”

“Lady Sister, you are little more than a child yourself, and these are dangerous times.”

I round on him and stamp my foot. “I am old enough to be married twice. I am old enough to be bedded without tenderness or consideration. I am old enough to face death in the confinement room and be told that my own mother-my own mother-has commanded them to save the child and not me! I think I am a woman now. I have a babe in arms, and I have been married and widowed and now betrothed again. I am like a draper’s parcel to be sent about like cloth and cut to the pattern that people wish. My mother told me that my father died by his own hand and that we are an unlucky family. I think I am a woman now! I am treated as a woman grown when it suits you all, you can hardly make me a child again!”

He nods as if he is listening to me and considering what I have to say. “You have cause for complaint,” he says steadily. “But this is the way of the world, Lady Margaret; we cannot make an exception for you.”

“But you should!” I exclaim. “This is what I have been saying since my childhood. You should make an exception for me. Our Lady speaks to me, the holy Joan appears to me, I am sent to be a light to you. I cannot be married to an ordinary man and sent away to God knows where again. I should be given a nunnery of my own and be an abbess! You should do this, Brother Jasper; you command Wales. You should give me a nunnery, I want to found an order!”

He holds the baby close and turns away from me a little. I think he is moved to tears by my righteous anger, but then I see his face is flushed and his shoulders are shaking because he is laughing. “Oh, my lord,” he says. “Forgive me, Margaret, but oh, my lord. You are a child, a child. You are a baby like our Henry here, and I shall care for both of you.”

“Nobody shall care for me,” I shout. “For you are all mistaken about me, and you are a fool to laugh at me. I am in the care of God, and I am not going to marry anyone! I am going to be an abbess.”

He catches his breath, his face still bright with laughter. “An abbess. Certainly. And will you be dining with us tonight, Reverend Mother?”

I scowl at him. “I shall be served in my rooms,” I say crossly. “I shall not dine with you. Possibly I shall never dine with you again. But you can tell Father William to come to me. I will have to confess trespassing against those who have trespassed against me.”

“I will send him,” Jasper says kindly. “And I will send the best of the dishes to your room. And tomorrow I hope you will meet me in the stable yard and I will teach you to ride on your own. A lady of your importance should have her own horse; she should ride a beautiful horse well. When you go back to England, I think you should go on your own fine horse.”

I hesitate. “I cannot be tempted by vanity,” I warn him. “I am going to be an abbess, and nothing will divert me. You shall see. You will all see. You shall not treat me as a thing for trading and selling. I shall command my own life.”

“Certainly,” he says pleasantly. “It is very wrong that you should feel we think of you like that, for I love and respect you, as I promised I would. I shall find you an expensive horse and you will look beautiful on his back and everyone will admire you, and it can all mean nothing to you at all.”

I sleep in a dream of white-washed cloister walls and a great library, where illuminated books are chained to the desks and I can go every day and study. I dream of a tutor who will lead me through Greek and Latin and even Hebrew, and that I will read the Bible in the tongue which is closest to the angels, and I will know everything. In my dream, my hunger for learning and my desire to be special is quieted, soothed. I think that if I could be a scholar, I could live in peace. If I could wake every day to the discipline of the offices of the day, and spend my days in study, I think I would feel that I was living a life that was pleasing to God and to me. I would not care whether people thought I was special, if my life was truly special. It would not matter to me that people could see me as pious, if I could truly live as a woman scholar of piety. I want to be what I seem to be. I act as if I am specially holy, a special girl; but this is what I really want to be. I really do.

In the morning, I wake and dress, but before I go for my breakfast I go to the nursery to see the baby. He is still in his cradle, but I can hear him cooing, little quiet noises like a duckling quacking to itself on a still pond. I lean over his cradle to see him, and he smiles. He does. There is an unmistakable recognition in his dark blue eyes, and the funny, gummy, triangular grin that makes him at once less like a pretty doll, and tremendously like a little person.

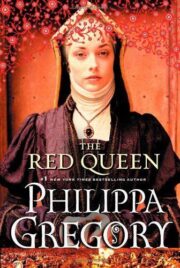

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.