The flush that comes to her face tells me that she does not want me to ask the servants, that they have been warned never to discuss this matter with me. Something happened twelve years ago that she wanted to forget, that she wanted me never to know. Something shameful happened.

“How did he die?” I ask.

“By his own hand,” she says quickly and quietly. “If you must know. If you insist on knowing his shame. He left you and he left me, and he died by his own hand. I was with child, a baby that I lost. I lost a baby in my shock and my grief, a baby that might have been a son for the House of Lancaster; but he didn’t think about that. It was days before your first birthday; he didn’t care enough for either of us even to wait to see you into your second year. And that is why I have always told you that your future lies in your son. A husband can come and go; he can leave on his own account. He can go to war or get sick or kill himself; but if you make your son your own, your own creation, then you are safe. A boy is your guardian. If you had been a boy, I would have poured my life into you. You would have been my destiny.”

“But since I was a girl you did not love me, and he did not wait to see my birthday?”

She looks at me honestly and repeats the dreadful words. “Since you were a girl, of course not. Since you were a girl you could only be the bridge to the next generation; you could be nothing more than the means by which our family gets a boy.”

There is a short silence while I absorb my mother’s belief in my unimportance. “I see. I see. I am lucky to be valued by God, since I am not valued by you. I was not valued by my father.”

She nods as if it does not matter much. Still she does not understand me. She will never understand. She will never think that I am worth the effort of understanding. To her I am, as she so frankly tells me, a bridge.

“So why did my father kill himself?” I return to her first revelation. “Why would he do such a thing? His soul will have gone to hell. They must have told a string of lies to get him buried in holy ground.” I correct myself. “You must have told a string of lies.”

My mother comes back and sinks onto the bench by the warm fire. “I did what I could to protect our good name,” she says quietly. “As anyone of a great name would do. Your father came back from France with stories of victory, but then people started to whisper. They said he had done nothing of any value, indeed he had taken the troops and money that his commander Richard of York-the great hero-needed to hold France for England. Richard of York was making progress, but your father set it back. Your father set siege to a town, but it was the wrong town, owned by the Duke of Brittany, and he had to return it to them. We nearly lost the alliance with Brittany through his folly. That would have cost the country dear, but he did not think of it. He set a tax to raise money in the defeated areas of France, but it was illegal; and worse, he kept all the revenue for himself. He said he had a great campaign plan; but he led his men round in circles and then brought them home again without either victory or plunder, so they were bitter against him and said that he was a false lord to them. He was dearly loved by our king, but not even the king could pretend that he had done well.

“There would have been an inquiry in London about his conduct; he escaped that shame only by his death. There might even have been an excommunication from the pope. They would have come for your father and accused him of treason, and he would have paid with his life on the block, and you would have lost your fortune, and we would have been attainted and ruined; he spared us that, but only by running away into death.”

“An excommunication?” I am more horrified by this than anything else.

“People wrote ballads about him,” she says bitterly. “People laughed at his stupidity and marveled at our infamy. You cannot imagine the shame of it. I have shielded you from it, from the shame of him, and I get no thanks for it. You are such a child you don’t know that he is notorious as the great example of his age of the change of fortune, of the cruelty of the wheel of fortune. He could not have been born with better prospects and better opportunities; but he was unlucky, fatally unlucky. In his very first battle in France, when he rode out as a boy, he was captured, and he was left in captivity for seventeen years. It broke his heart. He thought that nobody cared enough to ransom him. Perhaps that is the lesson that I should have taught you-never mind your studies, never mind your nagging for books, for a tutor, for Latin lessons. I should have taught you never to be unlucky, never to be unlucky like your father.”

“Does everyone know?” I ask. I am horrified at the shame I have inherited, unknowingly. “Jasper, for instance? Does Jasper know I am the daughter of a coward?”

My mother shrugs. “Everyone. We said that he was exhausted by campaigning, and died of his service to the king. But people will always gossip about their betters.”

“And are we an unlucky family?” I ask her. “Do you think I have inherited his bad luck?”

She will not answer me. She gets to her feet and smooths the skirt of her gown as if to brush away smuts from the fire, or to sweep away ill fortune.

“Are we unlucky?” I ask. “Lady Mother?”

“Well, I am not,” she says defensively. “I was born a Beauchamp, and after your father’s death I married again and changed my name from his. Now I am a Welles. But you might be unlucky. The Beauforts may be. But perhaps you will change the luck,” she says indifferently. “You were lucky enough to have a boy, after all. Now you have a Lancaster heir.”

They serve dinner very late; the Duke of Buckingham keeps court hours and is not troubled by the cost of candles. At least the meat is better cooked and there are more side dishes of pastries and sweetmeats than at Pembroke Castle. I see that at this table where everything is so beautiful, Jasper’s manners are positively courtly, and I understand for the first time that he lives as a soldier when he is in his border castle on the very frontiers of the kingdom, but he is a courtier when he is in a great house. He sees me watching him, and he winks at me as if we two share the secret of how we manage our lives when we do not have to be on our best behavior.

We eat a good dinner and afterwards there is an entertainment, some fools, a juggler, and a girl who sings. Then my mother nods to me and sends me to bed as if I were a child still, and before the grand company I can do nothing but curtsey for her blessing and go. I glance at my future husband as I leave. He is looking at the girl singer with his eyes narrowed, a little smile on his mouth. I don’t mind walking out after I see that look. I am more sick of men, all men, than I dare to acknowledge to myself.

Next day, the horses are in the stable yard, and I am to be sent back to Pembroke Castle until my year of mourning is finished and I can be married again to the smiling stranger. My mother comes to bid me farewell and watches the manservant lift me onto the pillion saddle behind Jasper’s master of horse. Jasper himself is riding ahead with this troop of guards. The rear file are waiting for me.

“You will leave your son in the care of Jasper Tudor when you marry Sir Henry,” my mother remarks, as if this arrangement has just occurred to her this minute, as I am leaving.

“No, he will come with me. Surely, he will come with me,” I blurt out. “He must come with me. He is my son. Where should he be, but with me?”

“It’s not possible,” she says decidedly. “It is all agreed. He is to stay with Jasper. Jasper will care for him and keep him safe.”

“But he is my son!”

My mother smiles. “You are little more than a child yourself. You cannot look after an heir to our name, and keep him safe. These are dangerous times, Margaret. You should understand that by now. He is a valuable boy. He will be safer if he is at some distance from London, while the Yorks are in power. He will be safer in Pembroke than anywhere else in the country. Wales loves the Tudors. Jasper will guard him as his own.”

“But he is my own! Not Jasper’s!”

My mother comes closer and puts her hand on my knee. “You own nothing, Margaret. You yourself are the property of your husband. Once again I have chosen a good husband for you, one near to the crown, kinsman to the Nevilles, son of the greatest duke in England. Be grateful, child. Your son will be well cared for, and then you will have more, Stafford boys this time.”

“I nearly died last time,” I burst out, careless of the man seated before me on the horse, his shoulders squared, pretending not to listen.

“I know,” my mother says. “And this is the price of being a woman. Your husband did his duty and died. You did yours and survived. You were lucky this time; he was not. Let’s hope you take your luck onwards.”

“What if I am not so lucky next time? What if I have the Beaufort luck, and next time the midwives do as you ordered them and let me die? What if they do as you command and drag a grandson out of your daughter’s dead body?”

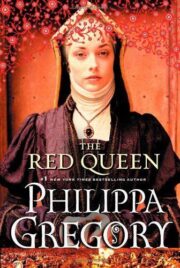

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.