My lady governess comes into the room. “Your brother-in-law Jasper asks you to agree to his name for the baby,” she says. “He is writing to the king and to your mother to tell them he is going to call him Edmund Owen, for the baby’s father and his Tudor grandfather.”

“No,” I say. I am not going to name my baby, who cost me so much pain, after a man who caused me nothing but pain. Or his stupid father. “No, I won’t call him Edmund.”

“You can’t call him Edward,” she says. “The king’s son is Prince Edward.”

“I am going to call him Henry,” I say, thinking of the sleeping king who might wake for a boy of the House of Lancaster called Henry, though he slept through the birth of the prince called Edward. “Henry is a royal name for England, some of our best and bravest kings have been called Henry. This boy will be Henry Tudor.” I repeat the name proudly: “Henry Tudor.” And I think to myself, when the sleeping King Henry VI is dead, then this baby will be Henry VII.

“He said Edmund Owen,” she repeats, as if I might be deaf as well as stupid.

“And I say Henry,” I say. “And I have called him this already. This is his name. It is decided. I have named him in my prayers. He is all but baptized Henry already.”

She raises her eyebrows at my ringing emphasis. “They won’t like it,” she says, and she goes out of the room to tell my brother-in-law Jasper that the girl is being stubborn and will not name her son for her dead husband, but has chosen her own name for him and will not be dissuaded.

I lie back against the pillows again and close my eyes. My boy will be Henry Tudor, whatever anyone says.

SPRING 1457

I have to stay in my rooms for another six weeks after the birth of my boy, before I can go to the chapel and be cleansed of the sin of childbirth. When I come back to my rooms, the shutters are down and the dark drapes have been taken away. There is wine in jugs and small cakes on plates, and Jasper has come to visit me and congratulate me on the birth of my child. The nursemaids tell me that Jasper visits the baby in his nursery every day, as if he were the doting father himself. He sits by the cradle if the baby is asleep, he touches his cheek with his finger, he cups the tightly wrapped head in his big hands. If the baby is awake, Jasper watches him feed, or he stands over them when they unwrap the swaddling and admires the straight legs and the strong arms. They tell me that Jasper begs them to leave the swaddling off for a moment more so he can see the little fists and the fat little feet. They think it unmanly for him to hang over the cradle, and I agree; but all the Tudors please only themselves.

He smiles at me tentatively, and I smile back. “Are you well, sister?” he asks.

“I am,” I say.

“They tell me it was a difficult birth for you.”

“It was.”

He nods. “I have a letter from your mother for you, and she also wrote to me.”

He hands me one sheet of paper, folded square and sealed with my mother’s Beaufort crest of the portcullis. I lift the seal carefully and read her letter. She has written in French, and she commands me to meet her at Greenfield House in Newport, Gwent. That is all. She sends me no words of affection or inquiry after my son, her own grandson. I remember that she told them if it was a choice between a boy and me, then they should let me die, and I ignore her coldness and turn to Jasper. “Does she tell you why I am to go to Newport? For she does not trouble herself to explain to me.”

“Yes,” he says. “I am to take you with an armed escort, and your baby is to stay here. You are to meet with Humphrey, the Duke of Buckingham. It is his house.”

“Why am I to see him?” I ask. I have a distant memory of the duke, who heads one of the great wealthy families of the kingdom. We are cousins of some sort. “Is he to be my new guardian? Can’t you be my guardian now, Jasper?”

He looks away. “No. It’s not that.” He tries to smile at me, but his eyes are soft with pity. “You are to be married again, my sister. You are to be married to the Duke of Buckingham’s son, as soon as your year of mourning is finished. But the contract of marriage and the betrothal is to take place now. You are to marry the duke’s son: Sir Henry Stafford.”

I look at him, and I know my face is horrified. “I have to marry again?” I blurt out, thinking of the agony of childbirth and the likelihood that it will kill me another time. “Jasper, can I refuse to go? Can I stay here with you?”

He shakes his head. “I am afraid not.”

MARCH 1457

A parcel-taken from one place to another, handed from one owner to another, unwrapped and bundled up at will-is all that I am. A vessel, for the bearing of sons, for one nobleman or another: it hardly matters who. Nobody sees me for what I am: a young woman of great family with royal connections, a young woman of exceptional piety who deserves-surely to God! – some recognition. But no, having been shipped to Lamphey Castle in a litter, I now ride to Newport on a fat cob, seated behind a manservant, unable to see anything of the road ahead of me and glimpsing muddy fields and pale pasturelands only through the jogging ranks of the men-at-arms. They are armed with lances and cudgels and are wearing the badge of the Tudor crest at their collars. Jasper is leading the way on his warhorse, and he has warned them to be prepared for ambush from Herbert’s men, or trouble on the road from bands of thieves. Once we get closer to the sea there is also the danger of a marauding party of pirates. This is how I am protected. This is the country I live in. This is what a good king, a strong king, should prevent.

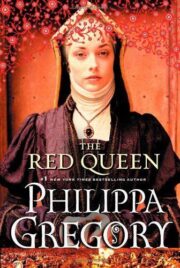

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.