The midwife thinks that the baby will come early. She feels my belly and says that he is lying wrongly, but he may turn in time. Sometimes, she says, babies turn very late. It is important that they come out headfirst; I don’t know why. She does not mention any details to Jasper, but I know that he paces up and down outside my chamber every day. I can hear the floorboards creak as he tiptoes north and south, as anxious as a loving husband. Since I am in confinement I can see no man, and that is a great relief. But I do wish I could come out to church. Father William, here at Pembroke, was moved to tears by my first confession. He said he had never met a young woman of more piety. I was glad at last to find someone who understands me. He is allowed to pray with me if he sits on one side of the screen and I the other, but it is not nearly as inspiring as praying before a congregation, where everyone can see me.

After a week, I start to have terrible pain in the very bones of my body when I am walking the narrow confines of the chamber, and Nan the midwife and her fellow crone, whose name sounds something like a squawk, and who speaks no English at all, agree that I had better go to bed and not walk anymore, not even stand. The pain is so bad I could almost believe that the bones are breaking inside me. Clearly, something has gone wrong, but nobody knows what it is. They ask the physician, but since he cannot lay a hand on me, nor do more than ask me what I think might be the matter, we get no further forwards. I am thirteen years old and small for my age. How am I to know what is going wrong with the baby in my body? They keep asking me, does it really feel as if my bones are breaking inside me? And when I say yes, then they look at one another as if they fear it must be true. But I can’t believe that I will die in childbirth. I can’t believe that God will have gone to all this trouble to get me here in Wales, with a child who might be king in my womb, only to have me die before he is even born.

They speak of sending for my mother, but she is so far away and the roads are so dangerous now that she cannot come, and besides, she would know no better than them. Nobody knows what is wrong with me, and now they remark that I am too young and too small to be with child at all, which is rather belated advice and no comfort to me now I am so close to the birth. I have not dared to ask how the baby is actually going to come out of my belly. I fear very much that I am supposed to split open like a small pod for a fat pea, and then I am certain to bleed to death.

I had thought the pain of waiting was the worst pain I could endure, but that was only until the night when I wake to an agony as if my belly were heaving up and turning over inside me. I scream in shock, and the two women bounce up from their trestle beds and my lady governess comes running, and my maid, and in a moment the room is filled with candles and people fetching hot water and firewood and among it all, nobody is even looking at me, though I can feel a sudden flood pour out of me, and I am certain that it is blood and I am bleeding to death.

They fly at me and give me a lathe to bite on, and a sacred girdle to tie around my heaving belly. Father William has sent the Host in the Monstrance from the chapel, and they put it on my prie dieu so I can fix my eyes on the body of the Lord. I have to say I am much less impressed by crucifixion now that I am in childbirth. It is really not possible that anything could hurt more than this. I grieve for the suffering of Our Lord, of course. But if He had tried a bad birth He would know what pain is.

They hold me down on the bed but let me heave on a rope when the pains start to come. I faint once for the agony of it, and then they give me a strong drink, which makes me giddy and sick, but nothing can free me from the vice that has gripped on my belly and is tearing me apart. This goes on for hours, from dawn till dusk, and then I hear them muttering to each other that the timing of the baby is wrong, it is taking too long. One of the midwives says to me that she is sorry but they are going to have to toss me in a blanket to make the baby come on.

“What?” I mutter, so confused with pain that I don’t know what she means. I don’t understand what they are doing as they help me off the bed and bid me lie on a blanket on the floor. I think perhaps they are doing something that will relieve the gripping pain which makes me cry out until I think I can bear no more. So I lie down, obedient to their tugging hands, and then the six of them gather round and lift the blanket between them. I am suspended like a sack of potatoes, and then they pull the blanket all at once and I am thrown up and drop down again. I am only a small girl of thirteen, they can throw me up into the air, and I feel a terrible flying and falling sensation and then the agony of landing and then they fling me up again. Ten times they do this while I scream and beg them to stop, and then they heave me back into the bed and look at me as if they expect me to be much improved while I hang over the side of the bed and vomit between sobs.

I lie back for a moment, and for a blessed moment the worst of it stops. In the sudden silence I hear my lady governess say, very clearly: “Your orders are to save the baby if you have to choose. Especially if it is a boy.”

I am so enraged at the thought of Jasper ordering my own lady governess to tell my midwives that they should let me die if they have to choose between my life or that of his nephew that I spit on the floor and cry out: “Oh, who says so? I am Lady Margaret Beaufort of the House of Lancaster …” But they don’t even hear me; they don’t turn to listen to me.

“That’s the right thing to do,” Nan agrees. “But seems hard on the little maid …”

“It is her mother’s order,” my lady governess says, and at once I don’t want to shout at them anymore. My mother? My own mother told my lady governess that if the baby and I were in danger then they should save the baby?

“Poor little girl. Poor, poor little girl,” Nan says, and at first I think she is speaking of the baby, perhaps it is a girl after all. But then I realize she is speaking of me, a girl of thirteen years, whose own mother has said that they can let her die as long as a son and heir is born.

It takes two days and nights for the baby to make his agonizing way out of me, and I do not die, though there are long hours when I would have done so willingly, just to escape the pain. They show him to me, as I am falling asleep, drowning in pain. He is brown-haired, I think, and he has tiny hands. I reach out to touch him, but the drink and the pain and the exhaustion flood over me like darkness and I faint away.

When I wake, it is morning and one of the shutters is opened, the yellow winter sun is shining in the little panes of glass, and the room is warm with the banked-up fire glowing in the fireplace. The baby is in his cradle, swaddled tight on his board. When the nursemaid hands him to me, I cannot even feel his body, he is wrapped so tight in the swaddling bands that are like bandages from head to toe. She says he has to be strapped to his board so his arms and legs cannot move, so his head is kept still, to make sure that his young bones grow straight and true. I will be allowed to see his feet and his hands and his little body when they unwrap him to change his clout, which they will do at midday. Until then I can hold him while he sleeps, like a stiff little doll. The swaddling cloth is wrapped around his head and chin to keep his neck straight, and it finishes with a little loop on the top of his head. The poor women use the loop to hook their babies up on a roof beam when they are cooking, or doing their work, but this boy, who is the newest baby in the House of Lancaster, will be rocked and carried by a team of nursemaids.

I lie him down on the bed beside me and gaze at his tiny face, his little nose, and the smiling curves of his rosy eyelids. He is not like a living thing, but more like a little stone carving of a baby as you find in a church, placed beside his stone-dead mother. It is a miracle to think that such a thing has been made, has grown, has come into the world; that I made him, almost entirely on my own (for I hardly count Edmund’s drunken labors). This tiny little object, this miniature being, is the bone of my bone and the flesh of my flesh, and he is of my making, all of my making.

After a little while he wakes and starts to cry. For such a small object the cry is incredibly loud, and I am glad the nursemaid comes in at a run and takes him from the room to the wet nurse. My own small breasts ache to suckle him, but I am bound up as tight as my swaddled baby; the two of us are strapped tight to do our duty: a baby who must grow straight, and a young mother who may not feed her child. His wet nurse has left her own baby at home so that she can come and take up her position in the castle. She will eat better than she has ever eaten in her life before, and she is allowed a good ration of ale. She does not even have to care for my baby, she just has to make milk for him, as if she were a dairy cow. He is brought to her when he needs feeding, and the rest of the time he is cared for by the maids of the nursery. She does a little cleaning, washing his clouts and linen, and helps in his rooms. She does not hold him except at feeding time. He has other women to do that. He has his own rocker to sleep by his cradle, his own two nursemaids to wait on him, his own physician comes once a week, and the midwives will stay with us until I am churched and he is christened. He has a larger entourage than me, and I suddenly realize that this is because he is more important than me. I am Lady Margaret Tudor, born a Beaufort, of the House of Lancaster, cousin to the sleeping King of England. But he is both a Beaufort and a Tudor. He has royal blood on both sides. He is Earl of Richmond, of the House of Lancaster, and has a claim, after the king’s son, Prince Edward, to the throne of England.

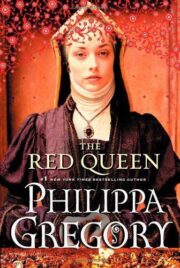

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.