“Bamming, Ger, bamming! I know this humour, and shan’t be taken-in!”

The Earl laughed, kissed the tips of his fingers to him, and vanished into the Castle.

He was received in his bedchamber by Turvey, who palpably winced at the sight of him. “I know, Turvey, I know!” he said. “My coat will never be the same again, do what you will, and I am sure you will do everything imaginable! As for my cravat, I might as well wear a Belcher handkerchief, might I not?”

“I am relieved to see that your lordship has sustained no serious injury,” responded Turvey repressively.

“You must be astonished, I daresay, for you believe me to be a very fragile creature, don’t you?”

“The tidings which were brought to the Castle by Miss Bolderwood were of a sufficiently alarming nature to occasion anxiety, my lord.”

“Oh, so that is how the news was spread!”

“Miss Bolderwood had but just stepped down from my Lord Ulverston’s curricle when your lordship’s horse bolted past them. I understand that the young lady sustained a severe shock. Permit me, my lord, to relieve you of your coat!”

The Earl was seated at his dressing-table when, some twenty minutes later, Ulverston came into his room. He was dressed in his shirt and his satin knee-breeches, and was engaged on the delicate operation of arranging the folds of a fresh cravat into the style known as the Napoleon. At his elbow stood Turvey, intently watching the movements of his slender fingers. A number of starched cravats hung over the valet’s forearm, and three or four crumpled wrecks lay on the floor at his feet. The Earl’s eyes lifted briefly to observe his friend in the mirror. “Hush!” he said. “Pray do not speak, Lucy, or do anything to distract my attention!”

“Fop!” said the Viscount.

Turvey glanced at him reproachfully, but Gervase paid no heed. He finished tying the cravat, gazed thoughtfully at his reflection for perhaps ten seconds, while Turvey held his breath, and then said: “My coat, Turvey!”

A deep sigh was breathed by the valet. He carefully disposed the unwanted cravats across the back of a chair, and picked up a coat of dark blue cloth.

“And what do you call that pretty confection?’’ enquired Ulverston.

“The Napoleon — how can you be so ignorant? Do you think I ought not to wear it?”

“No, but I wonder you don’t start a fashion of your own! Earthquake à la St. Erth! How’s that, dear boy?”

Turvey gave a discreet cough. “If I may be permitted to say so, my lord, the Desborough tie already enjoys a considerable degree of popularity in the highest circles. We are at present perfecting the design of the Stanyon Fall, which, when disclosed, will, I fancy take the ton by storm.”

“You should not betray our secrets, Turvey,” Gervase said, standing up to allow the valet to help him to put on his coat. “Thank you: nothing more!”

Turvey bowed, and turned away to gather up the discarded riding-coat and breeches. The Earl had picked up a knife from his dressing-table, and was trimming his nails, and did not immediately look up. The valet paused, laid the breeches down again, and thrust a hand into the tail-pocket of the coat. He drew forth the coil of thin cord which was spoiling the set of the coat, and in the same instant the Earl raised his head, and perceived what he was doing. A shadow of annoyance crossed his face; he said, with rather more sharpness than was usually heard in his voice: “Yes, leave that here!”

The slight bow with which Turvey received this order expressed to a nicety his opinion of those who carried coils of cord in their pockets. He was about to lay the cord on the chair when the Viscount stepped forward, and took it out of his hand.

“You may go.” The Earl’s head was bent again over his task.

Ulverston returned to the fireplace, testing the cord by jerking a length of it between his hands. When Turvey had withdrawn, he said: “Saw a whole front rank brought down by that trick once. Mind, that was at night! — ambush!”

The Earl said nothing.

“Stupid thing to do, to leave it in your pocket, dear boy!”

“Very.”

Ulverston tossed the coil aside. “Out with it, Ger! That’s what happened, ain’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Martin?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, one thing you do know is that he was in the grounds at the time!”

“So you say.”

“Dash it, it was Clarence who said so, and what reason had he to say it if it wasn’t true?”

“None. I don’t doubt it: I fancy Martin generally does take a gun out at sundown.”

“Well, what do you mean to do?” Ulverston demanded.

“Nothing.”

“Famous!” said Ulverston. “That fairly beats the Dutch! I collect that a little thing like that — ” he jerked his chin towards the cord — “don’t even give you to think?”

“On the contrary, it gives me furiously to think. My reflections on this event may be false, and are certainly unpleasant, and with your good leave, Lucy, I’ll keep them to myself.”

“This won’t serve!” Ulverston said. “You cannot do nothing when an attempt has been made to kill you!”

“Very well, what would you wish me to do?” Gervase asked, laying down the paring-knife. He glanced at the Viscount’s scowling countenance, and smiled. “You don’t know, do you? Shall I announce to the household that I was thrown by such a trick? Or shall I accuse my brother of wishing to make away with me?”

“Send him packing!”

“On what grounds?”

“Good God, ain’t these grounds enough?”

“Yes, if I could prove them.”

“There’s your proof!” the Viscount said, pointing to the cord.

“My dear Lucy, proof that someone tried to play a malicious trick on me, but not proof that my death was intended.”

“Stuff!” the Viscount said explosively. “How can you stand there talking such crack-brained nonsense to me, Ger?”

“Well, I am not dead, am I?”; said Gervase. “I am not even hurt, and that I was stunned for a moment or two might be thought a mischance. If I had not fallen with my head upon the carriage-drive, that would not have occurred.”

“What the devil are you trying to make me believe now?” demanded Ulverston, staring at him. “Do you take this to have been a schoolboy prank? There is no schoolboy in the case!”

“Oh, don’t you think so? I find Martin not a step removed from that state. I own, I do not perfectly understand him, but it is sufficiently plain to me that he thinks I should be the better for a sharp set-down. You heard what passed at the table this morning: ‘St. Erth is perfection itself!’ was what he said before he flung himself out of the room. Well! it would certainly have afforded him satisfaction had I, the day you came here, suffered a ducking in a muddy stream. I did not do so, so perhaps I had instead to be made to rumble off my horse — such a nonpareil among horsemen am I said to be! By the way, I wonder who did say so?”

“It don’t matter who said it, or if no one said it!” replied the Viscount, quite exasperated. “This is all a damned hum! Your precious brother ain’t such a boy that he didn’t know the thing might have had fatal consequences!”

“If he had paused to consider the matter at all,” agreed St. Erth. “It is quite a question, you know, whether he does pause to consider what may be the outcome of his more headlong actions. Come in!”

A knock had sounded on the door, and this opened to admit Theo. Gervase instantly said: “Oh, the devil! No. Go away, Theo! Lucy has said it all for you!”

Theo shut the door, and advanced into the room. “No use, Gervase! I am determined to know what happened to you this afternoon. Ulverston has already said enough to make me uneasy — and I beg that you won’t insult my intelligence with any more tales of stumbling into rabbit-holes, for they won’t fadge!”

“All you’ll get from Ger is a bag of moonshine!” said the Viscount roundly. “The plain truth is that his horse was brought down by a cord stretched across his path — and there is the cord, if you doubt me!”

“Oh, my God!” Theo said. “Martin?”

His cousin shrugged. He walked over to the fire, and stood staring down into it, his face hard to read.

“What I’m saying is that it’s time Ger was rid of that lad!” announced the Viscount.

“Theo will not agree with you,” interposed Gervase. “We have spoken of this before today.”

“This had not happened then!” Theo said, slightly raising his head.

“Are you of another mind now?” Gervase asked, watching him.

Theo stood frowning. “No,” he said, at last. “No, I am not of another mind. If Martin did indeed do this — but do you know that? — I am of the opinion that it was done in one of his fits of blind, unreasoning rage. His quarrel with you last night, his sister’s teasing today — oh, I know Martin! He was as mad as a baited bear today, and in that mood he would not pause to consider the consequences of whatever foolish revenge he chose to take on you!”

“This,” said the Viscount, not mincing matters, “is all fudge!”

“You don’t know Martin as I do. But if he had a more dreadful purpose in mind — then I say keep him here, under your eye!”

The Viscount rubbed the tip of his nose reflectively. “Something to be said for that, Ger,” he admitted.

“I have no intention, at present, of driving him away from Stanyon,” Gervase said.

“Do you mean to charge him with today’s misadventure?” Theo asked.

“No, and I beg you will not either!”

“Very well. I certainly did no good by anything I said to him about his conduct over the bridge,” Theo said, with a wry grimace. “I wish I may not have goaded him into this. I begin to be sorry that I urged you to remain at Stanyon, Gervase. It might have been better, perhaps, to have given Martin time to have grown used to the thought that it is you who are master here now.”

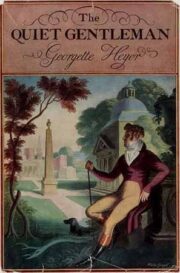

"The Quiet Gentleman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Quiet Gentleman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Quiet Gentleman" друзьям в соцсетях.