Gervase intervened hastily: “Grampound is a very good sort of a man, Louisa, but I doubt whether Martin wants to be told of his sayings. Let Theo take you back to the ballroom! It will occasion too much remark if we all go together.”

“I think it is you who had better accompany Lady Grampound,” said Theo bluntly.

“Nonsense! Martin and I have a little rubbed one another, but we are not going to come to fisticuffs, I assure you! Louisa, oblige me by not mentioning what has occurred to anyone! There is not the least occasion for you to speak of it even to Grampound.”

“The person who should be told, is Mama,” said her ladyship, gathering up her train. “However, I shall not do so, for she will never make the smallest push to remonstrate with Martin, and so it has always been!”

With these sisterly words, she accepted her cousin’s escort into the ballroom, where she proceeded to regale him, without loss of time, with the whole history of the episode.

Left alone with his half-brother, Gervase said in a more friendly tone: “Well, that was all very unfortunate, but it will be forgotten! If I spoke too warmly, I beg your pardon, but to be trying to kiss against her will a girl in Miss Bolderwood’s circumstances is the outside of enough, as well you know!”

His sensibilities as much lacerated by Marianne’s attempt to repulse him as by the lash of his own conscience, Martin was in no mood to accept an amende. He said in a shaking voice: “Damn you, leave me alone!” and brushed past Gervase out of the saloon.

Chapter 10

It was not to be expected that Miss Bolderwood could compose herself for slumber that night until she had poured forth the agitating events of the evening into her friend’s ears. Lord Ulverston’s kindness and good-humour had done much to calm her disturbed nerves, but these had been shocked, and would not readily recover. Since her schoolroom days she had almost never found herself alone with a man other than her Papa, for even when the Earl taught her to drive his curricle his groom had always been perched up behind the carriage. The anxious care of her parents had wrapped her about; and although her disposition led her to flirt with her many admirers it had never occurred to her innocent mind that these tactics might lead them, on the first occasion when they found her unprotected, to take shocking advantage of her levity. Her spirits were quite borne down by the discovery; and she was much inclined to think herself a fast girl, with whom gentlemen thought it proper to take liberties.

Miss Morville, however, received her confidences with admirable calm and common-sense. While agreeing that it was no doubt disagreeable to be found in such an embarrassing situation, she maintained that it was no matter for wonder that Martin should have so far forgotten himself. “If you will be so pretty, Marianne, and flirt so dreadfully, what can you expect?”

“Oh, I was never so mortified! I had not the least notion he would try to do such a thing!”

“Well, he should not, of course, but he is very young, after all, and I daresay he is ashamed of it now,” said Miss Morville consolingly. “If I were you, I would not refine too much upon the incident!”

“How can you talk so? He behaved as though I were — as though I were the veriest drab!”She saw that Miss Morville was looking amused, and added indignantly: “Drusilla, how can you be so insensible? You must have felt it as I do!”

“Perhaps I might,” acknowledged Miss Morville. “I don’t think I should, but the melancholy truth is that no one has ever shown the smallest desire to kiss me!”

“I envy you!” declared Marianne. “I wish I knew how I am to face Martin at breakfast tomorrow! I cannot do it!”

“Oh, there will not be the smallest difficulty!” Miss Morville pointed out. “It is tomorrow already, and if you partake of breakfast at all it will be in this room, and not until many hours after the gentlemen have eaten theirs.”

This practical response was not very well-received, Marianne saying rather pettishly that Drusilla seemed not to enter into her feelings at all, and pointing out that whether it was at the breakfast-table or at the dinner-table her next meeting with Martin must cause her insupportable embarrassment.

“I daresay it will cause him embarrassment too,” observed Miss Morville, “so the sooner you have met, and can put it all behind you, the easier you will be.”

“If only I might go home!” Marianne said.

“Well, and so you will, in a day or two. To run away immediately would be to give rise to the sort of comment I am sure you would not like; and, you know, you can scarcely continue to reside in the same neighbourhood without encountering Martin.”

There could be no denying the good-sense of this remark. Marianne shed a few tears; and after animadverting indignantly on Martin’s folly, effrontry, and ill-breeding, turned from the contemplation of his depraved character to dwell with gratitude on the exquisite tact and kindness of Lord Ulverston.

“I can never be sufficiently obliged to him!” she declared. “I am persuaded he cannot have remained in ignorance of my distress, for I was so much mortified I could scarcely speak, and as for meeting his gaze, it was wholly beyond my power! I was ready to sink for fear he should ask me what was the matter, but he never did! There was something so very kind in the way he offered me his arm, and took me to drink a glass of lemonade, saying it was insufferably hot in the ballroom, and should I not like to go where it was cooler? And then, you know, we talked of all manner of things, until I was comfortable again, and I do think there was never anyone more good-natured.”

Miss Morville was very ready to encourage her in these happier reflections; and by dint of pointing out how sad it would be for Marianne to leave Stanyon before she had become better acquainted with his lordship, soon prevailed upon her to abandon this scheme. If her young friend’s artless panegyric left her with the suspicion that an embrace from the Viscount would have awakened no outraged feelings in her breast, this was a thought which she was wise enough to keep to herself.

Marianne was sure that she would be unable to close her eyes for what remained of the night. However that might have been, they were very peacefully closed for long after Miss Morville had left her bedchamber later in the morning. Miss Morville peeped into her room, but Marianne did not stir, and she left her to have her sleep out.

Only the gentlemen appeared at the breakfast-table, but by eleven o’clock most of the ladies had come downstairs from their rooms, including Lady Grampound, who seemed to have risen for no other purpose than to ensure that her sons were given rides by Martin. Upon his not unreasonably demurring at this demand, compliance with which must remove him from the Castle before any of the visitors had departed, she said that to oblige his nephews was the least he could do: an oblique reference to his misconduct which provoked him into replying that if giving rides to her brats would make her departure from Stanyon that day a certainty he would be happy to do it.

By noon, all the ball-guests except the Grampounds had left the Castle, and the Dowager was free to discuss the evening’s festivity with anyone so unwise as to approach her chair, to congratulate herself upon the excellence of the supper, and to enumerate all the guests who had been particularly gratified to have received invitations. In this innocuous amusement she was joined by her daughter, who could not conceive of greater bliss for her fellow-creatures than to find themselves at Stanyon, and who had further cause for complacence in having had her gown admired by the Duchess. The tempestuous entrance into the room of Harry and John, bursting to tell their Mama about the rides they had enjoyed, caused an interruption. Conversation became impossible, for when they had stopped shouting their news in unison to Lady Grampound they fell out over the rights of primogeniture, Harry contending that to ransack the contents of Grandmama’s netting-box was his privilege, and Johnny very hotly combating such a suggestion.

“Dear little fellows!” said the Dowager. “They would like to play a game, I daresay. How much they enjoyed playing at spillikins with dear Marianne yesterday!”

“Yes, indeed, Mama, but pray do not put it into their heads to do so again, for I told them they must not tease Miss Bolderwood to repeat her kindness.”

Marianne, who was engaged in restoring its contents to the netting-box, took the hint. She insisted that she would be very happy to play with the children, and went away to find the spillikins, while Lady Grampound informed her offspring of the treat in store for them. By the time Marianne returned, peace had been restored, even Johnny’s yells at being shrewdly kicked by his brother having ceased at the sight of a box of sugar-plums.

When Martin presently came into the room with Lord Ulverston, Marianne was too much engrossed with the game to accord him more than a brief, shy greeting. He said awkwardly that it was a particularly fine day, so that he thought she might care to walk in the shrubbery before luncheon was served. She declined it, and a moment later he had the mortification of seeing Ulverston join the spillikin-party, and receive a very welcoming smile and blush.

The Grampounds were to leave Stanyon during the afternoon, and while the party sat round the table in one of the saloons, eating cold meat and fruit, Lord Grampound expressed a wish to visit a house in the neighbourhood which he had some thought of hiring for the accommodation of his family during the summer months. This led his wife to explain in detail the extensive improvements which were to be put in hand at Grampound Manor, the fatal effects of Brighton air upon Harry’s liverish constitution, and her own ardent desire to spend the summer within reach of Stanyon. The Dowager, loftily disregarding her stepson’s claims to be consulted in the matter, at once invited her daughter to come to Stanyon itself, and to remain there for as long as she pleased, an invitation which her ladyship would certainly have accepted had Lord Grampound not intervened to say with great firmness that he preferred to hire a house of his own.

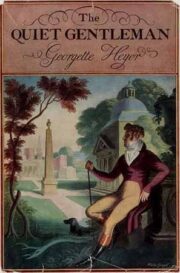

"The Quiet Gentleman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Quiet Gentleman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Quiet Gentleman" друзьям в соцсетях.