“I am Katherine,” I said.

“Katherine, my dear child…God bless you.”

He turned to the governess. “How long have the children been living here…like this?”

She told him when we had come.

“These are the Children of France,” he said. “It is unbelievable that they should live so.”

“We were sent here, Sire. We have done our best.”

“I know that well,” he replied. “Now…it will be different. Everything that is needed will be sent. I shall command it to be done and there will be no delay.”

I remember no more of that scene, but I had learned something. The mad man of the Hôtel de St.-Paul was our father and the King of France.

For several weeks after that we were warm and no longer hungry. New clothing came for us and there were fires in all the grates. There was plenty to eat. Life took on a different style.

Marie said: “Our prayers have been answered. God is good to us.”

I heard the governess say to the nurse: “I pray God the King stays sane.”

Her prayers were not answered for after a few months of good living, a carriage arrived at the door of the Hôtel. It brought our father. He had become the wild man again, and several strong men were needed to guard him as they brought him in.

We heard his shouting. He cried out that he was made of glass and that he was going to shatter into a thousand pieces.

I tried to visualize a glass man. I could not believe our father could be that.

I heard him call out: “I am unworthy. I do not deserve to live. Shoot me, I beg of you.”

I was deeply puzzled and after awhile the old bad times returned. It became a way of life and we accepted it as normal, as children do.

That was how it was in those days for us royal children in the Hôtel de St.-Paul.

When I was a little older, I realized that I had been unfortunate to be born at a time when my country was in a more desperate decline than it had ever been—and I hope will ever be again.

I ask myself where it began, and I think, if I am completely frank, I must say that it started with my father’s marriage. But perhaps it was even before that, for, as I learned so much later, my father’s mother, Joan of Bourbon, who had been a good wife and mother and cared greatly for her children, suffered from periodic bouts of madness; and it seemed that she had passed this malady on to my father.

Still, I am sure his marriage did nothing to help him, and at least that was responsible for much of the trouble which arose in our country. Perhaps it is ungrateful to blame the mother who brought one into the world, but many people did blame her. So why should not I? The Bible says, “Honor thy father and thy mother,” but how could I honor Isabeau of Bavaria, when I think I came near to hating her?

I saw very little of her during my childhood. There were so many of us that I believe she found it difficult to remember who we all were. It was only when we could be of use to her that she showed an interest in us. For the rest…we could be shut away in the Hôtel de St.-Paul, to be joined by our father during his bouts of insanity. I think there were fourteen of us, but I am not sure, because many of us did not survive birth.

My two eldest sisters, Isabelle and Jeanne, had pleased her because they had made advantageous marriages—and that was, of course, the fate intended for us all. Jeanne had married the powerful Duke of Brittany when she was about six, and had been sent to him to be brought up away from the licentious Court of France as a worthy little Breton. Isabelle had made an even more brilliant match; she had been sent to England to marry King Richard, and although only eight years old had become Queen of England.

So it was only when we were needed to forge some alliance that we were important to our mother. For the most part we could be left in obscurity, looked after by servants who were fond enough of us to stay and care for us, even though they were not always paid for their services.

She was very beautiful, our mother. And she had more than beauty. Her skin was very white, her large dark eyes luminous, her dark hair abundant and curly; and she had perpetual vitality. Much as I hated and feared her, I was aware of her allure which, as I grew older, I realized lay in an insatiable sensuality. It drew men to her even though they knew it could destroy them. She was like a siren singing on the rocks calling sailors to their destruction. They knew it and yet they could not resist, for she was irresistible, even to the most austere.

As soon as my father had seen her he had become desperately enamored of her and determined to marry her, which was just what those about him wanted, for she had been brought from Bavaria for that purpose. She had been fourteen years old at the time. He was about seventeen.

My poor father! My heart still overflows with pity for him. When we grew to know him, during his lucid periods, we all loved him. We used to be very distressed when we heard him, shouting that he was made of glass and would break into a thousand pieces.

Writing of it now, it seems incredible that members of the Royal House of Valois, the family of the reigning King, the Dauphin of France and his sisters and brothers could be living in conditions such as those prevailing in garrets in the back streets of Paris. But it was true—the only difference being that we were living in apartments which had been grand once if they were now shabby…and were probably more drafty than any attic in the slums.

My father had been at a disadvantage from the beginning, for he had been only twelve years old when he came to the throne. His father, known as Charles the Wise for obvious reasons, had always feared that his son might inherit the crown before he was of an age to govern.

Regencies brought trouble, said Charles the Wise. It meant that two or three ambitious men would be jostling for power—more concerned with doing good to themselves than to the country. He lowered the age of majority to fourteen, thinking he might live long enough to see his son reach that age.

My grandfather, though a wise man, was not a healthy one. When he was a very young man, his cousin, known as Charles the Bad, had attempted to poison him, and although the attempt had failed, the King had never fully regained his health, though with Joan of Bourbon he did have nine children, only three of whom survived infancy. Joan was the one who suffered from insanity.

Alas, Charles the Wise, as he had feared, died before his son, my father, reached his majority; and of course he was right when he said that regencies caused trouble.

My father was immediately taken in hand by his three uncles, the Dukes of Anjou, Berry and Burgundy. There was one other uncle who joined with them—his mother’s brother, the Duke of Bourbon. They were all ambitious men and for a short time they governed in a manner calculated to bring most profit to themselves.

Those counselors whom Charles the Wise had gathered together to assist him in the government of the country were immediately dismissed. That was the beginning of the trouble, because the uncles—always short of money—revived old taxes like the fouage and the gabelle—the hearth and salt taxes—which had always been unpopular; and the inevitable riots followed.

My father had greatly admired his father and had wanted to be like him. He loved his country, but by this time he was married to Isabeau and was coming more and more under her spell. She laughed at his seriousness, teased him and told him he should be more like his brother, Louis of Orléans. She wanted gaiety, extravagant parties, balls and masques at which she could appear in elaborate and sensational gowns. In this she was aided and urged to great extravagance by my father’s brother, Louis of Orléans, who was very handsome, dashing, witty, fascinating…and ambitious. He must have summed up the situation. My father wanted to be a good king, to follow his father’s methods…but alas, even more he wanted to please his wife.

Knowing my father and mother, I could well imagine the scenes between them: how she cajoled him; how he tried to resist; how she, with Louis of Orléans at her elbow, laughed at the serious young king; how she tempted him and how he succumbed.

There was constant trouble: perpetual strife with England, that old enemy; rivalry between the ducal uncles and Isabeau, with Louis of Orléans urging him to greater extravagant folly.

But my father earnestly wanted to do what was right and he knew that he was not acting as he should. There were riots throughout the country over the high taxation; affairs were going badly. He knew he must take drastic action, so he dismissed his uncles and recalled those counselors whom his father had chosen to help him govern the country.

The most important of these was Oliver de Clisson, whom he made his Constable.

Alas, Isabeau continued to charm him to such an extent that he still allowed lavish entertainments, in which he joined, to take place.

I do believe that he could have been a great king if my mother had not been there to lure him away from his duty.

It was not to be expected that the uncles would allow themselves to be lightly pushed aside. There was constant intriguing, and one night, when Oliver de Clisson was returning home from a banquet given by the King at the Hôtel de St.-Paul, he was set upon and badly wounded.

When news of this was brought to my father, he was just about to retire to bed. He was very disturbed and wanted to know where de Clisson was, and when he was told that he had been carried to a baker’s shop close to the spot where he had been struck down, the King immediately dressed and demanded to be taken to him.

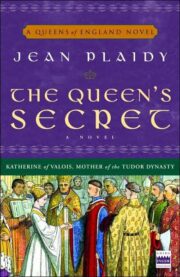

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.