Will Somers took Daniel’s hand and drew him toward her.

“Daniel Carpenter, Your Grace.” I could see she was holding herself together by a thread of will.

“Daniel.” She smiled at him. “You be a good boy when you grow up and a faithful man.” Her voice quavered for only a moment. She rested her beringed hand on his head. “God bless you,” she said gently.

That night as I waited for Danny to fall asleep I took a page of pressed notepaper and wrote to his father.

Dear Husband,

Living here, in the saddest court in Christendom with a queen who has never done anything but what she believed to be right and yet has been betrayed by everyone in the world that she loved, even those who were sworn before God to love her, I think of you and your long years of faithfulness to me. And I pray that one day we can be together again and you will see that I have learned to value love and to value fidelity; and to love and be faithful in return.

Your wife

Hannah Carpenter

Then I took the page, kissed his name at the top, and dropped it in the fire.

The court was due to leave for Whitehall Palace in August. The usual progress had been abandoned for the queen’s pregnancy, and now that there was no child it was almost as if she had abandoned the summer as well. Certainly there was no good weather to invite the court into the country. It was cold and raining every day, the harvest would be bad again and there would be starvation up and down the land. It would be another bad year of Mary’s reign, another year when God did not smile on England.

There was less fuss about moving than usual; there were fewer people traveling with the queen this year, fewer than ever before, and they had fewer goods, and hangers-on. The court was shrinking.

“Where is everybody?” I asked Will, bringing my horse beside his as we rode into the city at the head of the court train, just behind the queen in her litter.

“Hatfield,” he growled crossly.

The change of air did nothing for the queen, who complained that very night of a fever. She did not dine in the great hall of Whitehall Palace but took to her room and had two or three dishes brought to her. She hardly ate at all. I went past the great hall on my way to her chambers and stopped to glance in the door. For a moment I had a sudden powerful picture in my mind, almost as bright as a seeing: the empty throne, the greedily eating court, the ladies unsupervised, the servants kneeling to the empty throne and serving the royal dinner to the absent monarch on plates that would never be touched. It had been like this when I had first come to court, five years ago. But then it had been King Edward, sick and neglected in his rooms while the court made merry. Now it was my Queen Mary.

I stepped back and bumped into a man walking behind me. I turned with an apology. It was John Dee.

“Dr. Dee!” My heart thudded with fright. I dropped him a curtsey.

“Hannah Green,” he said, bowing over my hand. “How are you? And how is the queen?”

I glanced around to see that no one was in earshot. “Ill,” I said. “Very hot, aching in all her bones, weeping eyes and running nose. Sad.”

He nodded. “Half the city is sick,” he said. “I don’t think we’ve had one day of clear sunshine in the whole of this summer. How is your son?”

“Well, and I thank God for it,” I said.

“Has he spoken a word yet?”

“No.”

“I have been thinking of him and of our talk about him. There is a scholar I know, who might advise you. A physician.”

“In London?” I asked.

He took out a piece of paper. “I wrote down his direction, in case I should meet you today. You can trust him with anything that you wish to tell him.”

I took the piece of paper with some trepidation. No one would ever know all of John Dee’s business, all of his friends.

“Are you here to see my lord?” I asked. “We expect him tonight from Hatfield.”

“Then I shall wait in his rooms,” he said. “I don’t like to dine in the hall without the queen at its head. I don’t like to see an empty throne for England.”

“No,” I said, warming to him despite my fear, as I always did. “I was thinking that myself.”

He put his hand on mine. “You can trust this physician,” he said. “Tell him who you are, and what your child needs, and I know he will help you.”

Next day I took Danny on my hip and I walked toward the city to find the house of the physician. He had one of the tall narrow houses by the Inns of Court, and a pleasant girl to answer the door. She said he would see me at once if I would wait a moment in his front room, and Danny and I sat among the shelves which were filled with odd lumps of rock and stone.

He came quietly into the room and saw me examining a piece of marble, a lovely piece of rock, the color of honey.

“Do you have an interest in stones, Mistress Carpenter?” he asked.

Gently, I put the piece down. “No. But I read somewhere that there are different rocks occurring all over the world, some side by side, some on top of another, and no man has ever yet explained why.”

He nodded. “Nor why some carry coal and some gold. Your friend Mr. Dee and I were considering this the other day.”

I looked at him a little more closely, and I thought I recognized one of the Chosen People. He had skin that was the same color as mine, his eyes were as dark as mine, as dark as Daniel’s. He had a strong long nose and the arched eyebrows and high cheekbones that I knew and loved.

I took a breath and I took my courage and started without hesitation. “My name was Hannah Verde. I came from Spain with my father when I was a child. Look at the color of my skin, look at my eyes. I am one of the People.” I turned my head and stroked my finger down my nose. “See? This is my child, my son, he is two, he needs your help.”

The man looked at me as if he would deny everything. “I don’t know your family,” he said cautiously. “I don’t know what you mean by the People.”

“My father was a Verde in Aragon,” I said. “An old Jewish family. We changed our name so long ago I don’t know what it should have been. My cousins are the Gaston family in Paris. My husband has taken the name of Carpenter now, but he comes from the d’Israeli family. He is in Calais.” I checked when I found that my voice shook slightly at his name. “He was in Calais when the town was taken. I believe he is a prisoner now. I have no recent news of him. This is his son. He has not spoken since we left Calais, he is afraid, I think. But he is Daniel d’Israeli’s son, and he needs his birthright.”

“I understand you,” he said gently. “Is there any proof you can give me of your race and your sincerity?”

I whispered very low. “When my father died, we turned his face to the wall and we said: “Magnified and sanctified be the name of God throughout the world which He has created according to His will. May He establish His kingdom during the days of your life and during the life of all of the house of Israel, speedily, yea soon; and say ye, Amen.”

The man closed his eyes. “Amen.” And then opened them again. “What do you want with me, Hannah d’Israeli?”

“My son will not speak,” I said.

“He is mute?”

“He saw his wet nurse die in Calais. He has not spoken since that day.”

He nodded and took Daniel on to his knee. With great care he touched his face, his ears, his eyes. I thought of my husband learning his skill to care for the children of others, and I wondered if he would ever again see his own son, and if I could teach this child to say his father’s name.

“I can see no physical reason that he should not speak,” he said.

I nodded. “He can laugh, and he can make sounds. But he does not say words.”

“You want him circumcised?” he asked very quietly. “It is to mark him for life. He will be known as a Jew then. He will know himself as a Jew.”

“I keep my faith in my heart now,” I said, my voice little more than a whisper. “When I was a young woman I thought of nothing, I knew nothing. I just missed my mother. Now that I am older and I have a child of my own I know that there is more than the bond of a mother and her child. There is the People and our faith. Our little family lives within our kin. And that goes on. Whether his father is alive or dead, whether I am alive or dead, the People go on. Even though I have lost my father and my mother and now my husband, I acknowledge the People, I know there is a God, I know his name is Elohim. I still know there is a faith. And Daniel is part of it. I cannot deny it for him. I should not.”

He nodded. “Give him to me for a moment.”

He took Daniel into an inner room. I saw the dark eyes of my son look a little apprehensively over the strange man’s shoulder, and I tried to smile at him reassuringly as he was carried away. I went to the window and held on to the window latch. I clutched it so tightly that it marked my palms and I was not aware of it until my fingers had cramped tight. I heard a little cry from the inner room and I knew it was done, and Daniel was his father’s son in every way.

The rabbi brought my son out to me and handed him over. “I think he will speak,” was all he said.

“Thank you,” I replied.

He walked to the front door with me. There was no need for him to caution me, nor for me to promise him of my discretion. We both knew that on the other side of the door was a country where we were despised and hated for our race and for our faith, even though our race was the most lost and dispersed people in the world, and our faith was almost forgotten: nothing left but a few half-remembered prayers and some tenacious rituals.

“Shalom,” he said gently. “Go in peace.”

“Shalom,” I replied.

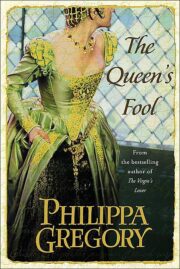

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.