“I am sure they will suit the purpose excellently,” I said with a pleasant smile. “And I thank you, your ladyship.”

Within a week I was desperate to leave, the bleak countryside of Sussex in winter seemed to press on my face like a pane of cold glass. The Downs leaned over the little castle as if they would crush us into the unresponsive chalky earth. The sky above the hills was iron gray, filled with snow. Within two weeks I had developed a headache which plagued me all the hours of daylight and would only leave me at night when I would fall into a sleep so deep that it could have been death.

Amy Dudley was a welcome and regular guest here. There was some debt between Sir John Philips and my lord which was repaid by his hospitality to Lady Dudley. Her stay was indefinite, no one remarked when she might leave, or where she might go next.

“Does she not have a house of her own?” I demanded of Mrs. Oddingsell in frustration.

“Not one that she chooses to use,” she said shortly and closed her lips tight on gossip.

I could not understand it. My lord had lost most of his great lands and fortune on his arrest for treason, but surely his wife must have had family and friends who would have kept at least a small estate for him?

“Where did she live when he was in the Tower?” I demanded.

“With her father,” Mrs. Oddingsell replied.

“Where is he now?”

“Dead, God rest his soul.”

Without a house to command or lands to farm, Lady Dudley was a woman of complete idleness. I never saw her with a book in her hand, I never saw her even write a letter. She rode out in the morning with only a groom for company on a long ride which lasted until dinner. At dinner she ate little and with no appetite. In the afternoon she would sit with Lady Philips and the two of them would gossip and sew. No detail of the Philips household, neighbors and friends was too small for their comment. When Mrs. Oddingsell and I sat with them I nearly fainted from sheer boredom as Lady Philips retold the story of Sophie’s disgrace, and Amelia’s remark, and what Peter had said about it all for the third time in three days.

Mrs. Oddingsell caught me yawning. “What ails you?” she demanded without sympathy.

“I am so bored,” I said frankly. “She gossips like a farmer’s wife. Why would she be interested in the lives of dairymaids?”

Mrs. Oddingsell gave me a quizzical look but said nothing.

“Does she have no friends at court, does she have no news from my lord, if she must tittle-tattle all afternoon?”

The woman shook her head.

We went to bed early, which was just as well for me, and Amy Dudley rose early in the morning. Ordinary days, ordinary to the point of boredom, but she went through them with an air of cold detachment, as if it were not her own precious life utterly wasted in nothings. She lived her life like a woman performing in a long pointless tableau. She went through her days like an automaton – like those I had seen in the treasure cases at Greenwich. A little golden toy soldier which could beat a drum or bend and straighten to fire a cannon. Everything she did, she did as if she were ticking along to do it on invisible wheels and her head turned and she spoke only when the cogs clicked inside her. There was nothing that brought her alive. She was in a state of obedient waiting. Then I realized what she was waiting for. She was waiting for a sign from him.

But there was no sign of Robert though January went into February. No sign of Robert though she told me he would come soon and set me to work, no sign of Robert though he clearly had not been arrested by the queen; whatever the blame for the loss of Calais, it was not to be laid at his door.

Amy Dudley was accustomed to his absence, of course. But when she had slept alone for all those years he had been in the Tower, she had known why she was alone in her marital bed. To everyone – to her father, to his adherents and kin – she was a martyr to her love for him, and they had all prayed for his return and her happiness. But now, it slowly must dawn on her, on everyone, that Lord Robert did not come home to his wife because he did not choose to do so. For some reason, he was in no hurry to be in her bed, in her company. Freedom from the Tower did not mean a return to the tiny scale of his wife’s existence. Freedom for Lord Robert meant the court, meant the queen, meant battlefields, politics, power: a wider world of which Lady Dudley had no knowledge. Worse than ignorance, she felt dread. She thought of the wider world with nothing but fear.

The greater world which was Lord Robert’s natural element was to her a place of continuous threat and danger. She saw his ambition, his natural God-given ambition, as a danger, she saw his opportunities all as risk. She was, in every sense of the word, a hopeless wife to him.

Finally, in the second week in February, she sent for him. One of his men was told to ride to the court at Richmond where the queen had entered her confinement chamber to have her child. Her ladyship told the servant to tell his lordship that she needed him at Chichester, and to wait to accompany him home.

“Why would she not write to him?” I asked Mrs. Oddingsell, surprised that Lady Dudley would broadcast to the world her desire that he should come home.

She hesitated. “She can do as she chooses, I suppose,” she said rudely.

It was her discomfiture that revealed the truth to me. “Can she not write?” I asked.

Mrs. Oddingsell scowled at me. “Not well,” she conceded reluctantly.

“Why not?” I demanded, a bookseller’s daughter to whom reading and writing was a skill like eating and walking.

“When would she learn?” Mrs. Oddingsell countered. “She was just a girl when she married him, and nothing more than a bride when he was in the Tower. Her father did not think a woman needed to know more than to sign her name, and her husband never spared the time to teach her. She can write, but slowly, and she can read if she has to.”

“You don’t need a man to teach you to read and write,” I said. “It is a skill a woman can get on her own. I could teach her, if she wanted it.”

Mrs. Oddingsell turned her head. “She wouldn’t demean herself to learn from you,” she said rudely. “She would only ever learn for him. And he does not trouble himself.”

The messenger did not wait, but came home straightaway, and told her that his lordship had said he would come to us for a visit shortly and in the meantime to assure her ladyship that all was well with him.

“I told you to wait for an answer,” she said irritably.

“My lady, he said he would see you soon. And the princess…”

Her head snapped up. “The princess? Which princess? Elizabeth?”

“Yes, the Princess Elizabeth swore that he could not go while they were all waiting for the queen’s child to be born. She said they could not endure another confinement which might go on for years. She could not abide it without him. And my lord said yes, he would leave, even a lady such as her, for he had not seen you since he came to England, and you had bidden him to come to you.”

She blushed a little at that, her vanity kindled like a flame. “And what more?” she asked.

The messenger looked a little awkward. “Just some jesting between my lord and the princess,” he said.

“What jesting?”

“The princess was witty about him liking court better than the country,” he said, fumbling for words. “Witty about the charms of the court. Said he would not bury himself in the fields with wife.”

The smile was quite wiped from her face. “And he said?”

“More jests,” he said. “I cannot remember them, my lady. His lordship is a witty man, and he and the princess…” He broke off at the look on her face.

“He and the princess: what?” she spat at him.

The messenger shuffled his feet and turned his hat in his hands. “She is a witty woman,” he said doltishly. “The words flew so fast between them I could not make out what they said. Something about the country, something about promises. Some of the time they spoke another language so it was secret between themselves… Certainly, she likes him well. He is a very gallant man.”

Amy Dudley jumped from her chair and strode to the bay window. “He is a very faithless man,” she said, very low. Then she turned to the messenger. “Very well, you can go. But next time when I order you to wait for him, I don’t want to see you back here without him.”

He threw a look at me which said very plainly that a servant could hardly command his master to return to his wife in the middle of a flirtation with the Princess of England. I waited till he had left the room and then excused myself and hared down the gallery after him, Danny bouncing along on my hip, clinging to my shoulder, his little legs gripped around my waist, as I ran.

“Stop! Stop!” I called. “Tell me about the court. Are all the physicians there for the queen? And the midwives? Is everything ready?”

“Aye,” he said. “She is expected to have the child in the middle of March, next month, God willing.”

“And do they say that she is well?”

He shook his head. “They say she is sick to her heart at the loss of Calais and the absence of her husband,” he said. “The king has not said he will come to England for the birth of his son, so she has to face the travail of childbed all alone. And she is poorly served. All her fortune has been thrown away on her army and her servants have not even been paid and cannot buy food in the market. It is like a ghost court, and now she has gone into confinement there is no one to watch over the courtiers at all.”

I felt a dreadful pang at the thought of her ill-served and me kicking my heels with Lady Amy Dudley, and doing nothing. “Who is with her?”

“Only a handful of her ladies. No one wants to be at court now.”

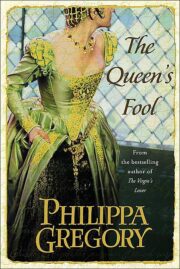

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.