“My child, where do you belong if not here? If not with me? If not with your husband?”

I had my answer: “I belong nowhere.”

My father shook his head. A young woman always had to be placed somewhere, she could not live unless she was bolted down in one service or another.

“Father, please let us set up a little business on our own, as we did in London. Let me help you in the printing shop. Let me live with you and we can be at peace and make our living here.”

He hesitated for a long moment, and suddenly I saw him as a stranger might see him. He was an old man and I was taking him from a home where he had become comfortable.

“What will you wear?” he asked finally.

I could have laughed out loud, it mattered so little to me. But I realized that it signified to him whether he had a daughter who could appear to fit into this world or whether I would be, eternally, out of step with it.

“I will wear a gown if you wish,” I said to please him. “But I will wear boots underneath it. I will wear a jerkin and a jacket on top.”

“And your wedding ring,” he stipulated. “You will not deny your marriage.”

“Father, he has denied it every day.”

“Daughter, he is your husband.”

I sighed. “Very well. But we can go, can we? And at once?”

He rested his hand on my face. “Child, I thought that you had a good husband who loved you and you would be happy.”

I gritted my teeth so the tears did not come to my eyes and make him think that I might soften, that I might still be a young woman with a chance of love. “No,” I said simply.

It was not an easy matter, stripping down the press again and moving it from the yard. I had only my new gowns and linen to take with me, Father had a small box of his clothes, but we had to move the entire stock of books and manuscripts and all the printing equipment: the clean paper, the barrels of ink, the baskets of bookbinding thread. It took a week before the porters had finished carrying everything from the Carpenters’ house to the new shop, and for every day of that week my father and I had to eat our dinner at a table in silence while Daniel’s sisters glared at me with aghast horror, and Daniel’s mother slammed down the plates with utter contempt as if she were feeding a pair of stray dogs.

Daniel stayed away, sleeping at his tutor’s house, coming home only for a change of clothes. At those times I made sure that I was busy with my father out the back, or packing up books under the shop counter. He did not try to argue with me or plead with me and, willfully, I felt it proved that I was right to leave him. I felt that if he had loved me he would have come after me, asked me again, begged me to stay. I willed myself to forget his stubbornness and his pride, and I made very sure to keep my thoughts from the life we had promised ourselves when we had said we would become the people we wanted to be and not be tied by the rules of Jew, or Gentile, or the world.

I had found a little shop at the south city gate: an excellent site for travelers about to leave Calais and travel through the English Pale to venture into France. It was the last chance they would have to buy books in their own language, and for those who wanted maps or advice about traveling in France or in the Spanish Netherlands we carried a good selection of travelers’ tales, mostly fabulous, it must be said, but good reading for the credulous. My father already had a reputation inside the city and his established customers soon found their way to the new premises. Most days he would sit in the sun outside the shop on one of the stools and I would work inside, bending over the press and setting type, now that there was no one to scold me for getting ink on my apron.

My father was tired, his move to Calais and then the disappointment of my failed marriage had wearied him. I was glad that he should sit and rest while I worked for the two of us. I relearned the skill of reading backward, I relearned the skill of the sweep of the ink ball, the flick of the clean sheet and the smooth heave on the handle of the press so that the typeface just kissed the whiteness of the paper and it came away clean.

My father worried desperately about me, about my ill-starred marriage, and about my future life, but when he saw that I had inherited all of his skill, and all of his love of books, he began to believe that even if he were to die tomorrow, I might yet survive on the business. “But we must save money, querida,” he would say. “You must be provided for.”

Autumn 1556

The first month in our little shop, I absolutely rejoiced in my escape from the Carpenter household. A couple of times I saw Daniel’s mother or two of his sisters in the market, or at the fish quay, and his mother looked away as if she could not see me, and his sisters pointed and nudged each other and stared as if I were a visiting leper and freedom was a disease that they might catch if they came too close. Every night in bed I spread myself out like a starfish, hands and feet pointing to each corner, rejoicing in the space, and thanked God that I might call myself a single woman once more with all the bed to myself. Every morning I awoke with an utter exultation that I need not fit myself to someone else’s pattern. I could put on my sound walking boots underneath the concealing hem of my gown, I could set print, I could go to the bakehouse for our breakfast, I could go with my father to the tavern for our dinner, I could do what I pleased; and not what a young married woman, trying to please a critical mother-in-law, had to do.

I did not see Daniel until midway through the second month and then I literally ran into him as I was coming out of church. I had to sit at the back now; as a deserting wife I was in a state of sin which nothing would remove but full penitence and a return to my husband if he would be kind enough to have me. The priest himself had told me that I was as bad as an adulteress, worse, since I was in a state of sin of my own making and not even at another’s urging. He set me a list of penances that would take me until Christmas next year to complete. I was as determined as ever to appear devout and so I spent many evenings on my knees in the church and always attended Mass, head shrouded in a black shawl, seated at the back. So it was from the darkness of the meanest pew that I stepped into the light of the church door and, half dazzled, bumped into Daniel Carpenter.

“Hannah!” he said, and put out a hand to steady me.

“Oh, Daniel.”

For a moment we stood, very close, our eyes meeting. In that second I felt a jolt of absolute desire and knew that I wanted him and that he wanted me, and then I stepped to one side and looked down and muttered: “Excuse me.”

“No, stop,” he said urgently. “Are you well? Is your father well?”

I looked up at that with an irrepressible giggle. Of course he knew the answers to both questions. With spies like his mother and sisters he probably knew, to the last letter, what pages I had on the press, what dinner we had in the cupboard.

“Yes,” I replied. “Both of us. Thank you.”

“I have missed you sorely,” he said, quickly trying to detain me. “I have been wanting to speak with you.”

“I am sorry,” I said coldly. “But I have nothing to say, Daniel, excuse me, please.”

I wanted to get away from him before he led me into talking, before he made me feel angry, or grieved, or jealous all over again. I did not want to feel anything for him, not desire, not resentment. I wanted to be cold to him, so I turned on my heel and started to walk away.

In two strides he was beside me, his hand on my arm. “Hannah, we cannot live apart like this. It is wrong.”

“Daniel, we should never have married. It is that which was wrong; not our separation. Now let me go.”

His hand dropped to his side but he still held my gaze. “I shall come to your shop this afternoon at two,” he said firmly. “And I shall talk with you in private. If you go out I shall wait for your return. I will not leave things like this, Hannah. I have the right to talk with you.”

There were people coming out of the church porch, and others waiting to enter. I did not want to attract any more attention than I had already earned by being the deserting bride of Calais.

“At two o’clock, then,” I said, and dipped him a tiny curtsey and went down the path. His mother and his sisters, coming into church behind him, drew their skirts back from the very paving slabs of the path where I was walking, as if they were afraid they would get the hems dirty by being brushed by me. I smiled at them, brazening it out. “Good morning, Miss Carpenters,” I said cheerily. “Good morning, Mrs. Carpenter.” And when I was out of earshot I said: “And God rot the lot of you.”

Daniel came at two o’clock and I drew him out of the house and up the stone stairs beside our house that went up to the roof of the gateway of the city walls that overlooked the English Pale and then south toward France. In the lee of the city walls, just outside, were new houses, built to accommodate the growing English population. If the French were ever to come against us these new householders would have to abandon their hearths and skip inside the gates. But before the French could come close, there were the canals which would be flooded from the sea gates, the eight great forts, the earth ramparts, and a stubborn defense plan. If they could get through that, they would have to face the fortified town of Calais itself and everyone knew that it was impregnable. The English themselves had only won it, two centuries ago, after a siege lasting eleven months and then the Calais burghers had surrendered, starved out. The walls of this city had never been breached. They never would be breached, it was a citadel that was famous for being impossible to take either by land or sea.

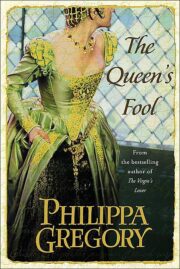

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.