I could not do it. I would not do it. I sat back on my heels with the book in my hand with the light of the fire flickering and dying down and realized that not even when I was in mortal danger could I bring myself to burn a book.

It went against the grain of me. I had seen my father carry some of these books across Christendom, strapped to his heart, knowing that the secrets they contained were newly named as heretical. I had seen him buy books and sell books and, more than that, lend and borrow them just for the joy of seeing their learning go onward, spread outward. I had seen his delight in finding a missing volume, I had seen him welcome a lost folio back to his shelves as if it were the son he had never had. Books were my brothers and sisters; I could not turn against them now. I could not become one of those that see something they cannot understand, and destroy it.

When Daniel’s joy in the scholarship of Venice and Padua made my own heart leap with enthusiasm, it was because I too thought that someday everything could be known, nothing need be hidden. And either of these two books might contain the secret of the whole world, might hold the key to understanding everything. John Dee was a great scholar, if he took so much trouble to get hold of these volumes and send them in secret, they would be precious indeed. I could not bring myself to destroy them. If I burned them I was no better than the Inquisition which had killed my mother. If I burned them, I became as one of those who think that ideas are dangerous and should be destroyed.

I was not one of those. Even at risk to my life, I could not become one of those. I was a young woman living at the very heart of a world that was starting to ask questions, living at a time when men and women thought that questions were the most important thing. And who could say where these questions might take us? The tables that had come from my father for John Dee might contain a drug which would cure the plague, they might contain the secret of how to determine where a ship is at sea, they might tell us how to fly, they might tell us how to live forever. I did not know what I held in my hands. I could no more have destroyed it than I could have killed a newborn child: precious in itself, and full of unknowable promise.

With a heavy heart I took the two books and tucked them behind the more innocuous titles on my father’s shelf. I supposed that if the house was searched I could claim ignorance. I had destroyed the most dangerous part of the package: the wrapping, John Dee’s name written in my father’s hand. My father was far away in Calais and there was nothing directly to link us to Mr. Dee.

I shook my head, weary of lying in order to reassure myself. In truth, there were a dozen connections between me and Mr. Dee if anyone wanted to examine them. There were a dozen connections between my father and the scholar. I was known as Lord Robert’s fool, as the queen’s fool, as the princess’s fool, I was connected with everyone whose name was danger. All I could hope for was that the fool’s motley hid me, that the sea between England and Calais shielded my father, and that Mr. Dee’s angels guided him, and would protect him even when he was on the rack, even if his jailers gave him his faggot of kindling and made him carry it to the stake.

It was scant consolation for a girl who had spent her girlhood on the run, hiding her faith, hiding her sex, hiding herself. But there was nothing I could do now except to go on the run again, and my horror of running from England was greater than my terror of being caught. When my father had promised me that this would be my home, that I would be safe here, I had believed him. When the queen had put my head in her lap and twisted my hair into curls around her fingers, I had trusted her as I had trusted my mother. I did not want to leave England, I did not want to leave the queen. I brushed the dust off my jerkin, straightened my cap, and slipped out again to the street.

I got back to Hampton Court in time for breakfast. I ran up the deserted garden from the river and entered the palace by the stable door. Anyone seeing me would have thought that I had been riding in the early morning, as I so often did.

“Good day,” one of the pages said and I turned on him the pleasant smile of the habitual liar.

“Good day,” I replied.

“And how is the queen this morning?”

“Merry indeed.”

Like the curtains at the windows of her confinement chamber, shutting out the summer sun, the queen grew paler and faded through every day of the tenth month of her waiting. In contrast, as Elizabeth’s confidence grew her very presence, her hair, her skin, seemed to shine more brightly. When she swept into the confinement chamber, taking a stool to talk lightly, sing to her lute, or stitch incredibly fine baby clothes, the queen seemed to shrink into invisibility. The girl was a radiant sparkling beauty, even as she sat over her sewing and demurely bowed her flaming head. Beside her, hand on her belly, always waiting in case the child should move, Mary was becoming little more than a shadow. As the days wore on, through the long long month of June, she became like a shadow waiting for the birth of a shadow. She seemed hardly to be there at all, her baby seemed hardly to be there at all. They were both melting away.

The king was a driven man. Everything directed him toward a steady fidelity to his wife: her love for him, her vulnerable condition, the need to appease the English nobility and keep the council favorably disposed toward Spanish policy as the country sneered at the sterile Spanish king. He knew this, he was a brilliant politician and diplomat; but he could not help himself. Where Elizabeth walked, there he followed. When she rode, he called for his horse and galloped after her. When she danced, he watched her and called for them to play the music again. When she studied, he loaned her books and corrected her pronunciation like a disinterested schoolmaster, while all the time his eyes were on her lips, on the neck of her gown, on her hands clasped lightly in her lap.

“Princess, this is a dangerous game,” I warned her.

“Hannah, this is my life,” she said simply. “With the king on my side I need fear nothing. And if he were to be free to marry, then I could look to no better match.”

“Your sister’s husband? While she is confined with his child?” I demanded, scandalized.

Her downcast eyes were slits of jet. “I might think, as she did, that an alliance between Spain and England would dominate all of Christendom,” she said sweetly.

“Yes, the queen thought that, and yet all that has happened is that she has brought the heresy laws on the heads of her subjects,” I said tartly. “And brought herself to solitude in a darkened room with her heart breaking and her sister outside in the sunshine flirting with her husband.”

“The queen fell in love with a husband who married for policy,” Elizabeth decreed. “I would never be such a fool. If he married me it would be quite the reverse. I would be the one marrying for policy and he would be the one marrying for love. And we would see whose heart broke first.”

“Has he told you he loves you?” I whispered, aghast, thinking of the queen lost in her loneliness of the enclosed room. “Has he said he would marry you, if she died?”

“He adores me,” Elizabeth said with quiet pleasure. “I could make him say anything.”

It was hard to get news of John Dee without seeming overly curious. He had simply gone, as if he had never been, disappeared into the terrible dungeons of the Inquisition in England at St. Paul’s, supervised by Bishop Bonner, whose resolute questioning was feeding the fires of Smithfield at the rate of half a dozen poor men and women every week.

“What news of John Dee?” I asked Will Somers quietly, one morning when I found him recumbent on a bench, basking like a lizard in the summer sunshine.

“He’s not dead yet,” he said, barely opening an eye. “Hush.”

“Are you sleeping?” I asked, wanting to know more.

“I’m not dead yet,” he said. “In that, he and I have something in common. But I am not being stretched on the rack, nor being pressed with a hundred rocks on my chest, nor being taken for questioning at midnight, at dawn, and as a rough alternative to breakfast. So not that much in common.”

“Has he confessed?” I asked, my voice a little breath.

“Can’t have done,” Will said pragmatically. “Because if he had confessed he would be dead, and there his similarity to me would be ended, since I am not dead but merely asleep.”

“Will…” “Fast asleep and dreaming, and not talking at all.”

I went to find Elizabeth. I had thought of speaking to Kat Ashley but I knew she despised me for my mixed allegiances, and I doubted her discretion. I heard the blast of the hunting horns and I knew that Elizabeth would have been riding. I hurried down to the stable yard and was there as the hounds came streaming in, with the riders behind them. Elizabeth was riding a new black hunter, a gift from the king, her cap askew, her face glowing. The court was all dismounting and shouting for their grooms. I sprang forward to hold her horse and said quietly to her, unheard in the general noise, “Princess, do you have any news of John Dee?”

She turned her back to me and patted her horse’s shoulder. “There, Sunburst,” she said loudly, speaking to the horse. “You did well.” To me in an undertone she said: “They are holding him for conjuring and calculing.”

“What?” I asked, horrified.

She was absolutely calm. “They say that he attempted to cast the queen’s astrology chart, and that he summoned up spirits to foretell the future.”

“Will he speak of any others, doing this with him?” I breathed.

“If they charge him with heresy you should expect him to sing like a little blinded thrush,” she said, turning to me and smiling radiantly, as if it were not her life at stake as well as mine. “They’ll rack him, you know. No one can stand that pain. He will be bound to talk.”

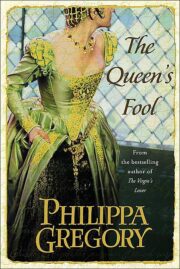

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.