“Enough,” she said sharply.

Will bowed. “But also like the king himself, the holy fool has greater gifts than a mere comical fool like me could tell,” he amended quickly.

“Why, what are they?” someone called out.

“The king gives joy to the most gracious lady in the kingdom, as I can only aspire to do,” Will said carefully. “And the holy fool has brought the queen her heart, as the king has most graciously done.”

The queen nodded at the recovery, and waved Will to his dinner place with the officers. He passed me with a wink. “Funny,” he said firmly.

“You upset the Spanish,” I said in an undertone. “And traduced me.”

“I made the court laugh,” he defended himself. “I am an English fool in an English court. It is my job to upset the Spanish. And you matter not a jot. You are grist, child, grist to the mill of my wit.”

“You grind exceeding small, Will,” I said, still nettled.

“Like God himself,” he said with evident satisfaction.

That night I went to bid good night to Lady Elizabeth. She was dressed in her nightgown, a shawl around her shoulders, seated by the fireside. The glowing embers put a warmth in her cheeks and her hair, brushed out over her shoulders, almost sparkled in the light from the dying fire.

“Good night, my lady,” I said quietly, making my bow.

She looked up. “Ah, the little spy,” she said unpleasantly.

I bowed again, waiting for her permission to leave.

“The queen summoned me, you know,” she said. “Straight after dinner, for a private chat between loving sisters. It was my last chance to confess. And if I am not mistaken that miserable Spaniard was hidden somewhere in the room, hearing every word. Probably both of them, that turncoat Pole too.”

I waited in case she would say more.

She shrugged her shoulders. “Well, no matter,” she said bluntly. “I confessed to nothing, I am innocent of everything. I am the heir and there is nothing they can do about it unless they find some way to murder me. I won’t stand trial, I won’t marry, and I won’t leave the country. I’ll just wait.”

I said nothing. Both of us were thinking of the queen’s approaching confinement. A healthy baby boy would mean that Elizabeth had waited for nothing. She would do better to marry now while she had the prestige of being heir, or she would end up like her sister: an elderly bride, or worse, a spinster aunt.

“I’d give a lot to know how long I had to wait,” she said frankly.

I bowed again.

“Oh, go away,” she said impatiently. “If I had known you were bringing me to court for a bedtime lecture from my sister I wouldn’t ever have come.”

“I am sorry,” I said. “But there was a moment when we both thought that court would be better for you than that freezing barn at Woodstock.”

“It wasn’t so bad,” Elizabeth said sulkily.

“Princess, it was worse than a pig’s hovel.”

She giggled at that, a true girl’s giggle. “Yes,” she admitted. “And being scolded by Mary is not as bad as being overwatched by that drudge Bedingfield. Yes, I suppose it is better here. It is only…” She broke off, and then rose to her feet and pushed the smoldering log with the toe of her slipper. “I would give a lot to know how long I have to wait,” she repeated.

I visited my father’s shop as he had asked me to do in his Christmas letter, to ensure that all was well there. It was a desolate place now; a tile had come from the roof in the winter storms and there was a damp stain down the lime-washed wall of my old bedroom. The printing press was shrouded in a dust sheet and stood beneath it like a hidden dragon, waiting to come out and roar words. But which ones would be safe in this new England where even the Bible was being taken back from the parish churches so that people could only hear from the priest and not read for themselves? If the very word of God was forbidden, then what books could be allowed? I looked along my father’s long shelves of books and pamphlets; half of them would now be called heresy, and it was a crime to store them, as we were doing here.

I felt a sense of great weariness and fear. For our own safety I should either spend a day here and burn my father’s books, or never come back here again. While they had cords of wood and torches stacked in great stores at Smithfield, a girl with a past like mine should not be in a room of books such as these. But these were our fortune, my father had amassed them over his years in Spain, collected them during his time in England. They were the fruit of hundreds of years of study by learned men and I was not merely their owner, I was their custodian. I would be a poor guardian if I burned them to save my own skin.

There was a tap at the door and I gasped in fright; I was a very timid guardian. I went into the shop, closing the door of the printing room with the incriminating titles behind me, but it was only our neighbor.

“I thought I saw you come in,” he said cheerfully. “Father not back yet? France too good to him?”

“Seems so,” I said, trying to recover my breath.

“I have a letter for you,” he said. “Is it an order? Should you hand it on to me?”

I glanced at the paper. It bore the Dudley seal of the bear and staff. I kept my face blandly indifferent. “I’ll read it, sir,” I said politely. “I’ll bring it to you if it is anything you would have in stock.”

“Or I can get manuscripts, you know,” he said eagerly. “As long as they are allowed. No theology, of course, no science, no astrology, no studies of the planets and planet rays, or the tides. Nothing of the new sciences, nothing that questions the Bible. But everything else.”

“I wouldn’t think there was much else, after you have refused to stock all that,” I said sourly, thinking of John Dee’s long years of inquiry which took in everything.

“Entertaining books,” he explained. “And the writings of the Holy Fathers as approved by the church. But only in Latin. I could take orders from the ladies and gentlemen of the court if you were to mention my name.”

“Yes,” I said. “But they don’t ask a fool for the wisdom of books.”

“No. But if they do…”

“If they do, I will pass them on to you,” I said, anxious for him to leave.

He nodded and went to the door. “Send my best wishes to your father when you see him,” he said. “The landlord says he can go on storing the press here until he can find another tenant. Business is so poor still…” He shook his head. “No one has any money, no one has the confidence to set up business while we wait for an heir and hope for better times. She’s well is she, God bless her? The queen? Looking well and carrying the baby high, is she?”

“Yes,” I said. “And only a few months to go now.”

“God preserve him, the little prince,” our neighbor said and devoutly crossed himself. Immediately I followed suit and then held the door for him as he went out.

As soon as I had the door barred I opened my letter.

Dear Mistress Boy,

If you can spare a moment for an old friend he would be very pleased to see you. I need some paper for drawing and some good pens and pencils, having turned to the consolation of poetry as the times are too troubled for anything but beauty. If you have such things in your shop please bring them, at your convenience, Robt. Dudley. (You will find me, at home to visitors, in the Tower, every day, there is no need to make an appointment.)

He was looking out of the window to the green, his desk drawn close to it to catch the light. His back was turned to me and I was across the room and beside him as he turned around. I was in his arms at once, he hugged me as a man would hug a child, a beloved little girl. But when I felt his arms come around me I longed for him as a woman desires a man.

He sensed it at once. He had been a philanderer for too many years not to know when he had a willing woman in his arms. At once he let me go and stepped back, as if he feared his own desire rising up to meet mine.

“Mistress Boy, I am shocked! You have become a woman grown.”

“I didn’t know it,” I said. “I have been thinking of other things.”

He nodded, his quick mind chasing after any allusion. “World changing very fast,” he observed.

“Yes,” I said. I glanced at the door which was safely closed.

“New king, new laws, new head of the church. Is Elizabeth well?”

“She’s been sick,” I said. “But she’s better now. She’s at Hampton Court, with the queen. I just came with her from Woodstock.”

He nodded. “Has she seen Dee yet?”

“No. I don’t think so.”

“Have you seen him?”

“I thought he was in Venice.”

“He was, Mistress Boy. And he has sent a package from Venice to your father in Calais, which your father will send on to the shop in London for you to deliver to him, if you please.”

“A package?” I asked anxiously.

“A book merely.”

I said nothing. We both knew that the wrong sort of book was enough to get me hanged.

“Is Kat Ashley still with the princess?”

“Of course.”

“Tell Kat from me, in secret, that if she is offered some ribbons she should certainly buy them.”

I recoiled at once. “My lord…”

Robert Dudley stretched out a peremptory hand to me. “Have I ever led you into danger?”

I hesitated, thinking of the Wyatt plot when I had carried treasonous messages that I had not understood. “No, my lord.”

“Then take this message but take no others from anyone else, and carry none for Kat, whatever she asks you. Once you have told her to buy her ribbons and once you have given John Dee his book, it is nothing more to do with you. The book is innocent and ribbons are ribbons.”

“You are weaving a plot,” I said unhappily. “And weaving me into it.”

“Mistress Boy, I have to do something, I cannot write poetry all day.”

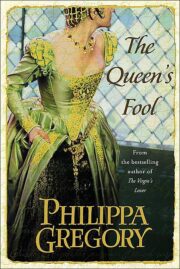

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.