“Knock again,” he said grimly. “And then break it down.”

At once the door yielded, swung open to our knock by an unenthusiastic pair of menservants who looked anxiously at the great men, the doctors in their furred coats and the men at arms behind them.

We marched into the great hall like enemies, without invitation. The place was in silence, extra rushes on the floor to muffle the sound of the servants’ feet, a strong smell of mint purifying the air. A redoubtable woman, Mrs. Kat Ashley, Elizabeth’s best servant and protector, was at the head of the hall, her hands clasped together under a solid bosom, her hair scraped back under an imposing hood. She looked the royal train up and down as if we were a pack of pirates.

The councillors delivered their letters of introduction, the physicians theirs. She took them without looking at them.

“I shall tell my lady that you are here but she is too sick to see anyone,” she said flatly. “I will see that you are served such dinner as we can lay before you; but we have not the rooms to accommodate such a great company as yourselves.”

“We will stay at Hillham Hall, Mrs. Ashley,” Sir Thomas Cornwallis said helpfully.

She raised her eyebrow as if she did not think much of his choice and turned to the door at the head of the hall. I fell into step behind her. At once she rounded on me.

“And where d’you think you’re going?”

I looked up at her, my face innocent. “With you, Mrs. Ashley. To the Lady Elizabeth.”

“She’ll see no one,” the woman ruled. “She is too ill.”

“Then let me pray at the foot of her bed,” I said quietly.

“If she is so very ill she will want the fool’s prayers,” someone said from the hall. “That child can see angels.”

Kat Ashley, caught out by her own story, nodded briefly and let me follow her out of the door, through the presence chamber and into Elizabeth’s private rooms.

There was a heavy damask curtain over the door to shut out the noise from the presence chamber. There were matching curtains at the window, drawn tight against light and air. Only candles illuminated the room with their flickering light and showed the princess, red hair spread like a hemorrhage on the pillow, her face white.

At once I could see she was ill indeed. Her belly was as swollen as if she were pregnant but her hands as they lay on the embroidered coverlet were swollen too, the fingers fat and thick as if she were a gross old lady and not a girl of twenty. Her lovely face was puffy, even her neck was thick.

“What is the matter with her?” I demanded.

“Dropsy,” Mrs. Ashley replied. “Worse than she has ever had it before. She needs rest and peace.”

“My lady,” I breathed.

She raised her head and peered at me from under swollen eyelids. “Who?”

“The queen’s fool,” I said. “Hannah.”

She veiled her eyes. “A message?” she asked, her voice a thread.

“No,” I said quickly. “I am come to you from Queen Mary. She has sent me to be your companion.”

“I thank her,” she said, her voice a whisper. “You can tell her that I am sick indeed and need to be alone.”

“She has sent doctors to make you better,” I said. “They are waiting to see you.”

“I am too sick to travel,” Elizabeth said, speaking strongly for the first time.

I bit my lip to hide my smile. She was ill, no one could manifest a swelling of the very knuckles of their fingers in order to escape a charge of treason. But she would play her illness as the trump card it was.

“She has sent her councillors to accompany you,” I warned her.

“Who?”

“Your cousin, Lord William Howard, among others.”

I saw her swollen lips twist in a bitter smile. “She must be very determined against me if she sends my own kin to arrest me,” she remarked.

“May I be your companion during your illness?” I suggested.

She turned her head away. “I am too tired,” she said. “You can come back when I am better.”

I rose from my kneeling position by the bed and stepped backward. Kat Ashley jerked her head toward the door to send me from the room.

“And you can tell those who have come to take her that she is near death!” she said bluntly. “You can’t threaten her with the scaffold, she is slipping away all on her own!” A half sob escaped her and I saw that she was drawn as tight as a lute string with anxiety for the princess.

“No one is threatening her,” I said.

She gave a little snort of disbelief. “They have come to take her, haven’t they?”

“Yes,” I said unwillingly. “But they have no warrant, she is not under arrest.”

“Then she shall not leave,” she said angrily.

“I’ll tell them she is too ill to travel,” I said. “But the physicians will want to see her, whatever I say.”

She made a little irritable puffing noise and stepped closer to the bed to straighten the quilt. I glimpsed a quick bright glance from beneath Elizabeth’s swollen eyelids, as I bowed again and let myself out of the room.

Then we waited. Good God, how we waited. She was the absolute mistress of delay. When the physicians said she was well enough to leave she could not choose the gowns she would bring, then her ladies could not pack them in time for us to set off before dusk. Then everything had to be unpacked again since we were staying another day, and then Elizabeth was so exhausted she could see no one at all the next day, and the merry dance of Elizabeth’s waiting began again.

During one of these mornings, when the big trunks were being laboriously loaded into the wagons, I went to the Lady Elizabeth to see if I could assist her. She was lying on a daybed, in an attitude of total exhaustion.

“It is all packed,” she said. “And I am so tired I do not know if I can begin the journey.”

The swelling of her body had reduced but she was clearly still unwell. She would have looked better if she had not powdered her cheeks with rice powder and, I swear, darkened the shadows under her eyes. She looked like a sick woman enacting the part of a sick woman.

“The queen is determined that you shall go to London,” I warned her. “Her litter arrived for you yesterday, you can travel lying down if you will.”

She bit her lip. “Do you know if she will accuse me when we get there?” she asked, her voice very low. “I am innocent of plotting against her, but there are many who would speak against me, slanderers and liars.”

“She loves you,” I reassured her. “I think she would take you back into her favor and into her heart even now, if you would just accept her faith.”

Elizabeth looked into my eyes, that straight honest Tudor look, like her father, like her sister. “Are you telling me the truth?” she asked. “Are you a holy fool or a trickster, Hannah Green?”

“I am neither,” I said, meeting her gaze. “I was begged for a fool by Robert Dudley, against my wishes. I never wanted to be a fool. I have a gift of Sight which comes to me unbidden, and sometimes shows me things that I cannot even understand. And most of the time it doesn’t come at all.”

“You saw an angel behind Robert Dudley,” she reminded me.

I smiled. “I did.”

“What was it like?”

I giggled, I couldn’t help it. “Lady Elizabeth, I was so taken with Lord Robert that I hardly noticed the angel.”

She sat up, quite forgetting her pose of illness, and laughed with me. “He is very… he is so… he is indeed a man you look at.”

“And I only realized it was an angel afterwards,” I said to excuse myself. “At the time I was just overwhelmed by the three of them, Mr. Dee, Lord Robert, and the third.”

“And do your visions come to pass?” she asked keenly. “You scried for Mr. Dee, didn’t you?”

I hesitated with a sense of the ground opening into a chasm under my feet. “Who says so?” I asked cautiously.

She smiled at me, a flash of small white teeth as if she were a bright fox. “Never mind what I know. I am asking what you know.”

“Some things that I see have come to pass,” I said, honestly enough. “But sometimes the very things I need to know, the most important things in the world, I cannot tell. Then it is a useless gift. If it had warned me – just once-”

“What warning?” she asked.

“The death of my mother,” I said. I would have bitten back the words as soon as they were spoken. I did not want to tell my past to this sharp-minded princess.

I glanced at her face but she was looking at me with intense sympathy. “I did not know,” she said gently. “Did she die in Spain? You came from Spain, did you not?”

“In Spain,” I said. “Of the plague.” I felt a sharp twist of pain in my belly at lying about my mother, but I did not dare to think of the fires of the Inquisition with this young woman watching me. It was as if she could have seen the flicker of their reflected flames in my eyes.

“I am sorry,” she said, very low. “It is hard for a young woman to grow up without a mother.”

I knew she was thinking of herself for a moment, and of the mother who had died on the scaffold with the names of witch, adulteress and whore. She put away the thought. “But what made you come to England?”

“We have kin here. And my father had arranged a marriage for me. We wanted to start again.”

She smiled at my breeches. “Does your betrothed know that he will be getting a girl who is half boy?”

I made a little pout. “He does not like me at court, he does not like me in livery, and he does not like me in breeches.”

“But do you like him?”

“Well enough as a cousin. Not enough for a husband.”

“And do you have any choice in the matter?”

“Not much,” I said shortly.

She nodded. “It’s always the same for all women,” she said, a hint of resentment in her voice. “The only people who can choose their lives are those in breeches. You do right to wear them.”

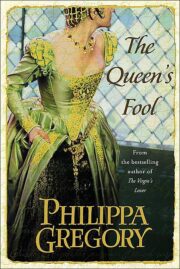

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.