“A queen will love him,” John Dee said. “He will be the greatest love of her life.”

“But she is to marry Philip of Spain,” I observed.

He shook his head. “I can’t see a Spaniard on the throne of England,” he predicted. “And neither can many others.”

It was hard to find a way to speak with the Lady Elizabeth without half the court remarking on it. Although she had no friends at court and only a small circle of her own household, she seemed to be continually surrounded by apparently casual passersby, half of whom were paid to spy on her. The French king had his spies in England, the Spanish emperor had his network. All the great men had maids and men in other households to keep watch for any signs of change or of treason, and the queen herself was creating and paying a network of informers. For all I knew, someone was paid to report on me, and the very thought of it made me sick with fear. It was a tense world of continual suspicion and pretend friendship. I was reminded of John Dee’s model of the earth with all the planets going around it. This princess was like the earth, at the very center of everything, except all the stars in her firmament watched her with envious eyes and wished her ill. I thought it no wonder that she was paler and paler and the shadows under her eyes were turning from the blue to the dark violet of bruises, as the Christmas feast approached and there was no goodwill from anyone for her.

The queen’s enmity grew every day that Elizabeth walked through the court with her head high, and her nose in the air, every time she turned away from the statue of Our Lady in the chapel, every time she left off her rosary and wore instead a miniature prayer book on a chain at her waist. Everyone knew that the prayer book contained her brother’s dying prayer: “Oh my lord God, defend this realm from Papistry and maintain thy true religion.” To wear this, in preference to the coral rosary that the queen had given her, was more than a public act of defiance, it was a living tableau of disobedience.

To Elizabeth, it was perhaps little more than a showy rebellion; but to our queen it was an insult that went straight to her heart. When Elizabeth rode out dressed in rich colors and smiling and waving, people would cheer her and doff their hats for her; when she stayed home in plain black and white people came to Whitehall Palace to see her dine at the queen’s table and remark on her fragile beauty and the plain Protestant piety of her dress.

The queen could see that although Elizabeth never openly defied her, she continually gave the gossipmongers material to take outside the court and to spread among those who kept to their Protestant ways:

“The Protestant princess was pale today, and did not touch the stoop of holy water.”

“The Protestant princess begged to be excused from evening Mass because she was unwell again.”

“The Protestant princess, all but prisoner in the Papist court, is keeping to her faith as best as she can, and biding her time in the very jaws of the Antichrist.”

“The Protestant princess is a very martyr to her faith and her plain-faced sister is as dogged as a pack of bear-baiters, hounding the young woman’s pure conscience.”

The queen, resplendent in rich gowns and delighting in her mother’s jewels, looked tawdry beside the blaze of Elizabeth’s hair, the martyr whiteness of her pallor and the extreme modesty of her black dress. However the queen dressed, whatever she wore, Elizabeth, the Protestant princess, gleamed with the radiance of a girl on the edge of womanhood. The queen beside her, old enough to be her mother, looked weary, and overwhelmed by the task she had inherited.

So I could not simply go to Elizabeth’s rooms and ask to see her. I might as well have announced myself to the ambassador from Spain who watched Elizabeth’s every step, and reported everything to the queen. But one day, as I was walking behind her in the gallery, she stumbled for a moment. I went to help her, and she took my arm.

“I have broken the heel on my shoe, I must send it to the cobbler,” she said.

“Let me help you to your rooms,” I offered, and added in a whisper, “I have a message for you, from Lord Robert Dudley.”

She did not even flicker a sideways glance at me, and in that absolute control I saw at once that she was a consummate plotter and that the queen was right to fear her.

“I can receive no messages without my sister’s blessing,” Elizabeth said sweetly. “But I would be very glad if you would help me to my chamber, I wrenched my foot when the heel broke.”

She bent down and took off her shoe. I could not help but notice the pretty embroidery on her stocking, but I thought it was not the time to ask her for the pattern. Always, everything she owned, everything she did, fascinated me. I gave her my arm. A courtier passing looked at us both. “The princess has broken the heel of her shoe,” I explained. He nodded, and went on. He, for one, was not going to trouble himself to help her.

Elizabeth kept her eyes straight ahead, she limped slightly on her stockinged foot and it made her walk slowly. She gave me plenty of time to deliver the message that she had said she could not hear without permission.

“Lord Robert asks you to summon John Dee as your tutor,” I said quietly. “He said, ‘without fail.’”

Still, she did not look at me.

“Can I tell him you will do so?”

“You can tell him that I will not do anything that would displease my sister the queen,” she said easily. “But I have long wanted to study with Mr. Dee and I was going to ask him to read with me. I am particularly interested in reading the teaching of the early fathers of the Holy Church.”

She shot one veiled glance at me.

“I am trying to learn about the Roman Catholic church,” she said. “My education has been much neglected until now.”

We were at the door of her rooms. A guard stood to attention as we approached and swung the door open. Elizabeth released me. “Thank you for your help,” she said coolly, and went inside. As the door shut behind her I saw her bend down and put her shoe back on. The heel was, of course, perfectly sound.

John Dee’s prediction that the men of England would rise up to prevent the queen marrying a Spaniard was proved every day in dozens of incidents. There were ballads sung against the marriage, the braver preachers thundered against a match so dangerous to the independence of the country. Crude drawings appeared on every lime-washed wall in the city, chap books were handed out slandering the Spanish prince, abusing the queen for even considering him. It was no help that the Spanish ambassador assured every nobleman at court that his prince had no interest in taking power in England, that the prince had been persuaded to the match by his father, that indeed Prince Philip, a desirable man of under thirty years might well have sought a bride to bring him more pleasure and profit than the Queen of England, eleven years his senior. Any suggestion that he wanted the match was proof of Spanish greed, any hint that he might have looked elsewhere was an insult.

The queen herself nearly collapsed under the weight of conflicting advice, under her great fear that she would lose the love of the people of England without gaining the support of Spain.

“Why did you say my heart would break?” she feverishly demanded of me, one day. “Was it because you could foresee it would be like this? With all my councillors telling me to refuse the match, and yet all of them telling me to marry and have a child without delay? With all the country dancing at my coronation and then, minutes later, all of them cursing the news of my wedding?”

“No,” I said. “I could not have foretold this. I think no one could have foretold such a turnaround in such a little time.”

“I have to guard against them,” she said, more to herself than to me. “At every turn I have to keep them at my beck and call. The great lords, and every man under them, have to be my loyal servants; but all the time they whisper in corners and set themselves up to judge me.”

She rose from her chair and walked the eight steps to the window, turned and walked back again. I remembered the first time I had seen her at Hunsdon, in the little court where she rarely laughed, where she was little more than a prisoner. Now she was Queen of England and still she was imprisoned by the will of the people, and still she did not laugh.

“And the council are worse than the ladies of my chamber!” she exclaimed. “They argue ceaselessly in my very presence, there are dozens of them but I cannot get a single sensible word of advice, they all desire something different, and they all – all of them! – lie to me. My spies bring me one set of stories, and the Spanish ambassador tells me others. And all the time I know that they are massing against me. They will pull me down from the throne and push Elizabeth on to it out of sheer madness. They will snatch themselves from the certainty of heaven and throw themselves into hell because they have studied heresy, and now they cannot hear the true word when it is given to them.”

“People like to think for themselves…” I suggested.

She rounded on me. “No, they don’t. They like to follow a man who is prepared to think for them. And now they think they have found him. They have found Thomas Wyatt. Oh yes, I know of him. The son of Anne Boleyn’s lover, whose side d’you think he is on? They have men like Robert Dudley, waiting on his chance in the Tower, and they have a princess like Elizabeth: a foolish girl, too young to know her own mind, too vain to take care, and too greedy to wait, as I had to wait, as I had to wait honorably, for all those long testing years. I waited in a wilderness, Hannah. But she will not wait at all.”

“You need not fear Robert Dudley,” I said quickly. “D’you not remember that he declared for you? Against his own father? But who is this Wyatt?”

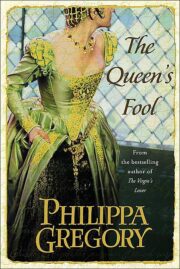

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.