He found a smile for me, though his face was weary from our long journey. “Do you, child?” he asked quietly. “That was a happy summer for us. She said…” He broke off. We never mentioned my mother’s name, even when we were alone. At first it had been a precaution to keep us safe from those who had killed her and would come after us, but now we were hiding from grief as well as from the Inquisition; and grief was an inveterate stalker.

“Will we live here?” I asked hopefully, looking at the beautiful riverside palaces and the level lawns. I was eager for a new home after years of traveling.

“Nowhere as grand as this,” he said gently. “We will have to start small, Hannah, in just a little shop. We have to make our lives again. And when we are settled then you will come out of boy’s clothes, and dress as a girl again, and marry young Daniel Carpenter.”

“And can we stop running?” I asked, very low.

My father hesitated. We had been running from the Inquisition for so long that it was almost impossible to hope that we had reached a safe haven. We ran away the very night that my mother was found guilty of being a Jew – a false Christian, a “Marrano” – by the church court, and we were long gone when they released her to the civil court to be burned alive at the stake. We ran from her like a pair of Judas Iscariots, desperate to save our own skins, though my father would tell me later, over and over again, with tears in his eyes, that we could never have saved her. If we had stayed in Aragon, they would have come for us too, and then all three of us would have died, instead of two being saved. When I swore that I would rather have died than live without her, he said very slowly and sadly that I would learn that life was the most precious thing of all. One day I would understand that she would have gladly given her life to save mine.

First over the border to Portugal, smuggled out by bandits who took every coin from my father’s purse and left him with his manuscripts and books, only because they could find no use for them. By boat to Bordeaux, a stormy crossing when we lived on deck without shelter from the scudding rain and the flying spray, and I thought we would die of the cold or drowning. We hugged the most precious books to our bellies as if they were infants that we should keep warm and dry. Overland to Paris, all the way pretending to be something that we were not: a merchant and his young apprentice-lad, pilgrims on the way to Chartres, itinerant traders, a minor lord and his pageboy traveling for pleasure, a scholar and his tutor going to the great university of Paris; anything rather than admit that we were new Christians, a suspicious couple with the smell of the smoke from the auto-da-fé still clinging to our clothes, and night terrors still clinging to our sleep.

We met my mother’s cousins in Paris, and they sent us on to their kin in Amsterdam, where they directed us to London. We were to hide our race under English skies, we were to become Londoners. We were to become Protestant Christians. We would learn to like it. I must learn to like it.

The kin – the People whose name cannot be spoken, whose faith is hidden, the People who are condemned to wander, banned from every country in Christendom – were thriving in secret in London as in Paris, as in Amsterdam. We all lived as Christians and observed the laws of the church, the feast days and fast days and rituals. Many of us, like my mother, believed sincerely in both faiths, kept the Sabbath in secret, a hidden candle burning, the food prepared, the housework done, so that the day could be holy with the scraps of half-remembered Jewish prayers, and then, the very next day, went to Mass with a clean conscience. My mother taught me the Bible and all of the Torah that she could remember together, as one sacred lesson. She cautioned me that our family connections and our faith were secret, a deep and dangerous secret. We must be discreet and trust in God, in the churches we had so richly endowed, in our friends: the nuns and priests and teachers that we knew so well. When the Inquisition came, we were caught like innocent chickens whose necks should be wrung and not slashed.

Others ran, as we had done; and emerged, as we had done, in the other great cities of Christendom to find their kin, to find refuge and help from distant cousins or loyal friends. Our family helped us to London with letters of introduction to the d’Israeli family, who here went by the name of Carpenter, organized my betrothal to the Carpenter boy, financed my father’s purchase of the printing press and found us the rooms over the shop off Fleet Street.

In the months after our arrival I set myself to learn my way around yet another city, as my father set up his print shop with an absolute determination to survive and to provide for me. At once, his stock of texts was much in demand, especially his copies of the gospels that he had brought inside the waistband of his breeches and now translated into English. He bought the books and manuscripts which once belonged to the libraries of religious houses – destroyed by Henry, the king before the young king, Edward. The scholarship of centuries was thrown to the winds by the old king, Henry, and every shop on each corner had a pile of papers that could be bought by the bushel. It was a bibliographer’s heaven. My father went out daily and came back with something rare and precious and when he had tidied it, and indexed it, everyone wanted to buy. They were mad for the Holy Word in London. At night, even when he was weary, he set print and ran off short copies of the gospels and simple texts for the faithful to study, all in English, all clear and simple. This was a country determined to read for itself and to live without priests, so at least I could be glad of that.

We sold the texts cheaply, at little more than cost price, to spread the word of God. We let it be known that we believed in giving the Word to the people, because we were convinced Protestants now. We could not have been better Protestants if our lives had depended on it.

Of course, our lives did depend on it.

I ran errands, read proofs, helped with translations, set print, stitched like a saddler with the sharp needle of the binder, read the backward-writing on the stone of the printing press. On days when I was not busy in the print shop I stood outside to summon passersby. I still dressed in the boy’s clothes I had used for our escape and anyone would have mistaken me for an idle lad, breeches flapping against my bare calves, bare feet crammed into old shoes, cap askew. I lounged against the wall of our shop like a vagrant lad whenever the sun came out, drinking in the weak English sunshine and idly surveying the street. To my right was another bookseller’s shop, smaller than ours and with cheaper wares. To the left was a publisher of chap books, poems and tracts for itinerant peddlers and ballad sellers, beyond him a painter of miniatures and maker of dainty toys, and beyond him a portrait painter and limner. We were all workers with paper and ink in this street, and Father told me that I should be grateful for a life which kept my hands soft. I should have been; but I was not.

It was a narrow street, meaner even than our temporary lodgings in Paris. Each house was clamped on to another house, all of them tottering like squat drunkards down to the river, the gable windows overhanging the cobbles below and blocking out the sky, so the pale sunshine striped the earth-plastered walls, like the slashing on a sleeve. The smell of the street was as strong as a farmyard’s. Every morning the women threw the contents of the chamber pots and the washing bowls from the overhanging windows and tipped the night-soil buckets into the stream in the middle of the street where it gurgled slowly away, draining sluggishly into the dirty ditch of the River Thames.

I wanted to live somewhere better than this, somewhere like the Princess Elizabeth’s garden with trees and flowers and a view down to the river. I wanted to be someone better than this: not a bookseller’s ragged apprentice, a hidden girl, a woman heading for betrothal to a stranger.

As I stood there, warming myself like a sulky Spanish cat in the sunshine, I heard the ring of a spur against a cobblestone and I snapped my eyes open and leaped to attention. Before me, casting a long shadow, was a young man. He was richly dressed, a tall hat on his head, a cape swinging from his shoulders, a thin silver sword at his side. He was the most breathtakingly handsome man I had ever seen.

All of this was startling enough, I could feel myself staring at him as if he were a descended angel. But behind him was a second man.

This was an older man, near thirty years of age, with the pale skin of a scholar, and dark deep-set eyes. I had seen his sort before. He was one of those who visited my father’s bookshop in Aragon, who came to us in Paris and who would be one of my father’s customers and friends here in London. He was a scholar, I could see it in the stoop of his neck and the rounded shoulders. He was a writer, I saw the permanent stain of ink on the third finger of his right hand; and he was something greater even than these: a thinker, a man prepared to seek out what was hidden. He was a dangerous man: a man not afraid of heresies, not afraid of questions, always wanting to know more; a man who would seek the truth behind the truth.

I had known a Jesuit priest like this man. He had come to my father’s shop in Spain, and begged him to get manuscripts, old manuscripts, older than the Bible, older even than the Word of God. I had known a Jewish scholar like this man, he too had come to my father’s bookstore and asked for the forbidden books, remnants of the Torah, the Law. Jesuit and scholar had come often to buy their books; and one day they had come no more. Ideas are more dangerous than an unsheathed sword in this world, half of them are forbidden, the other half would lead a man to question the very place of the earth itself, safe at the center of the universe.

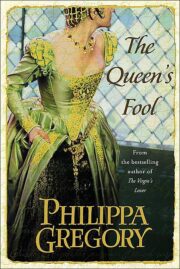

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.