The carter muttered to me that this was the case all around the country. The great religious houses, which had been the very backbone of England, had been emptied of the men and women who had been called by God to serve in them. The public good had been turned to private profit and there would never be public good again.

“If the poor king dies then Lady Mary will come to the throne and turn it all back,” he said. “She will be a queen for the people. A queen who returns us to the old ways.”

I reined back my pony. We were on the high road and there was no one within earshot but I was always fearful of anything that smacked of intrigue.

“And look at these roads,” he went on, turning on the box of the cart to complain over his shoulder. “Dust in summer and mud in winter, never a pot hole filled in, never a highwayman pursued. D’you know why not?”

“I’ll ride ahead, you’re right, the dust is dreadful,” I said.

He nodded and motioned me forward. I could hear his litany of complaint receding in the distance behind me:

“Because once the shrines are closed there are no pilgrims, and if there are no pilgrims then there is no one on the roads but the worst sort of people, and those that prey on them. Never a kind word, never a good house, never a decent road…”

I let the mare scramble up a little bank where the ground was softer beneath her small hooves and we ranged ahead of the cart.

Since I had not known the England that he said was lost, I could not feel, as he did, that the country was a lesser place. On that morning in early summer it seemed very fine to me, the roses twining through the hedgerows and a dozen butterflies hovering around the honeysuckle and the beanflowers. The fields were cultivated in prim little stripes, like the bound spine of a book, the sheep ranging on the upper hills, little fluffy dots against the rich damp green. It was a countryside so unlike my own that I could not stop marveling at it, the open villages with the black-and-white beamed buildings, and the roofs thatched with golden reeds, the rivers that seemed to melt into the roads in glassy slow-moving fords at every corner. It was a country so damp that it was no wonder that every cottage garden was bright green with growth, even the dung hills were topped with waving daisies, even the roofs of the older houses were as green as limes with moss. Compared to my own country, this was a land as sodden as a printer’s sponge, damp with life.

At first I noticed the things that were missing. There were no twisted rows of vines, no bent and bowed olive trees. There were no orchards of orange trees, or lemons or limes. The hills were rounded and green, not high and hot and rocky, and above them the sky was dappled with cloud, not the hot unrelieved blue of my home, and there were larks rising, and no circling eagles.

I rode in a state of wonder that a country could be so lush and so green; but even among this fertile wealth there was hunger. I saw it in the faces of some of the villagers, and in the fresh mounds of the graveyards. The carter was right, the balance that had been England at peace for a brief generation had been overthrown under the last king, and the new one continued the work of setting the country into turmoil. The great religious houses had closed and thrown the men and women who served and labored in them on to the roads. The great libraries were spilled and gone to waste – I had seen enough torn manuscripts at my father’s shop to know that centuries of scholarship had been thrown aside in the fear of heresy. The great golden vessels of the wealthy church had been taken by private men and melted down, the beautiful statues and works of art, some with their feet or hands worn smooth by a million kisses of the faithful, had been thrown down and smashed. There had been a great voyage of destruction through a wealthy peaceful country and it would take years before the church could be a safe haven again for the spiritual pilgrim or the weary traveler. If it ever could be made safe again.

It was such an adventure to travel so freely in a strange country that I was sorry when the carter whistled to me and called out, “Here’s Hunsdon now,” and I realized that these carefree days were over, that I had to return to work, and that now I had two tasks: one as a holy fool in a household where belief and faith were key concerns, and the other as a spy in a household where treason and tale-bearing were the greatest occupations.

I swallowed on a throat which was dry from the dust of the road and also from fear, I pulled my horse alongside the cart and we went in through the lodge gates together, as if I would shelter behind the bulk of the four turning wheels, and hide from the scrutiny of those blank windows that stared out over the lane and seemed to watch for our arrival.

Lady Mary was in her chamber sewing blackwork, the famous Spanish embroidery of black thread on white linen, while one of her ladies, standing at a lectern, read aloud to her. The first thing I heard, on reaching her presence, was a Spanish word, mispronounced, and she gave a merry laugh when she saw me wince.

“Ah, at last! A girl who can speak Spanish!” she exclaimed and gave me her hand to kiss. “If you could only read it!”

I thought for a moment. “I can read it,” I said, considering it reasonable that the daughter of a bookseller should be able to read her native tongue.

“Oh, can you? And Latin?”

“Not Latin,” I said, having learned of the danger of pride in my education from my encounter with John Dee. “Just Spanish and now I am learning to read English too.”

Lady Mary turned to her maid in waiting. “You will be pleased to hear that, Susan! Now you will not need to read to me in the afternoons.”

Susan did not look at all pleased to hear that she was to be supplanted by a fool in livery, but she took a seat on a stool like the other women and took up some sewing.

“You shall tell me all the news of the court,” the Lady Mary invited me. “Perhaps we should talk alone.”

One nod to the ladies and they took themselves off to the bay window and seated themselves in a circle in the brighter light, talking quietly as if to give us the illusion of privacy. I imagined every one of them was straining to hear what I might say.

“My brother the king?” she asked me, gesturing that I should sit on a cushion at her feet. “Do you have any messages from him?”

“No, Lady Mary,” I said, and saw her disappointment.

“I was hoping he would have thought of me more kindly, now he is so ill,” she said. “When he was a little boy I nursed him through half a dozen illnesses, I hoped he would remember that and think that we…”

I waited for her to say more but then she tapped her fingertips together as if to draw herself back from memories. “No matter,” she said. “Any other messages?”

“The duke sends you some game and some early salad leaves,” I said. “They came in the cart with the furniture, and have been taken round to your kitchens. And he asked me to give you this letter.”

She took it and broke the seal and smoothed it out. I saw her smile and then I heard her warm chuckle. “You bring me very good news, Hannah the Fool,” she said. “This is a payment under the will of my late father which has been owed to me all this long while, since his death. I thought I would never see it, but here it is, a draft on a London goldsmith. I can pay my bills and face the shopkeepers of Ware again.”

“I am glad of it,” I said awkwardly, not knowing what else to say.

“Yes,” she said. “You would have thought that King Henry’s only legitimate daughter would have had her fortune in her own hands by now, but they have delayed and withheld until I thought they wanted me to starve to death here. But now I come into favor.”

She paused, thoughtful. “The question which remains, is, why I am suddenly to be so well treated.” She looked speculatively at me. “Is Lady Elizabeth given her inheritance too? Are you to visit her with such a letter?”

I shook my head. “My lady, how would I know? I am only a messenger.”

“No word of it? She’s not at court visiting my brother now?”

“She wasn’t there when I left,” I said cautiously.

She nodded. “And he? My brother? Is he better at all?”

I thought of the quiet disappearance of the physicians who came so full of promises and then left after they had done nothing more than torture him with some new cure. On the morning that I had left Greenwich, the duke had brought in an old woman to nurse the king: an old crone of a midwife, skilled only in the birthing of children and the laying out of the dead. Clearly, he was not going to get any better.

“I don’t think so, my lady,” I said. “They were hoping that the summer would ease his chest but he seems to be as bad as ever.”

She leaned toward me. “Tell me, child, tell me the truth. Is my little brother dying?”

I hesitated, unsure of whether it was treason to tell of the death of the king.

She took my hand and I looked into her square determined face. Her eyes, dark and honest, met mine. She looked like a woman you could trust, a mistress you could love. “You can tell me, I can keep a secret,” she said. “I have kept many many secrets.”

“Since you ask it, I will tell you: I am certain that he is dying,” I admitted quietly. “But the duke denies it.”

She nodded. “And this wedding?”

I hesitated. “What wedding?”

She tutted in brief irritation. “Of Lady Jane Grey to the duke’s son, of course. What do they say about it at court?”

“That she was unwilling, and he not much better.”

“And why did the duke insist?” she asked.

“It was time that Guilford was married?” I hazarded.

She looked at me, as bright as a knife blade. “They say no more than that?”

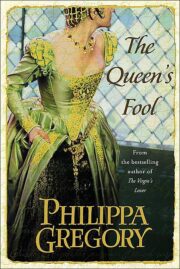

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.