For a moment, I did not understand what he meant, and then I gasped. “Daniel, he is your son! This is your son by your woman. This is her son. We were running from the French horsemen and she fell, she gave him to me as she went down. I am sorry, Daniel. She died at once. And this is your boy, I passed him off as mine. He is my boy now. He is my boy too.”

“He is mine?” he asked wonderingly. He looked at the child for the first time and saw, as anyone would have to see, the dark eyes which were his own, and the brave little smile.

“He is mine too,” I said jealously. “He knows that he is my boy.”

Daniel gave a little half laugh, almost a sob, and put his arms out. Danny reached for his father and went confidingly to him, put his plump little arms around his neck, looked him in the face and leaned back so he could scrutinize him. Then he thumped his little fist on his own chest and said, by way of introduction: “Dan’l.”

Daniel nodded, and pointed to his own chest. “Father,” he said. Danny’s little half-moon eyebrows raised in interest.

“Your father,” Daniel said.

He took my hand and tucked it firmly under his arm, as he held his son tightly with the other. He walked to the dispatching officer and gave his name and was ticked off their list. Then together we walked toward the open portcullis.

“Where are we going?” I asked, although I did not care. As long as I was with him and Danny, we could go anywhere in the world, be it flat or round, be it the center of the heavens or wildly circling around the sun.

“We are going to make a home,” he said firmly. “For you and me and Daniel. We are going to live as the People, you are going to be my wife, and his mother, and one of the Children of Israel.”

“I agree,” I said, surprising him again.

He stopped in his tracks. “You agree?” he repeated comically.

I nodded.

“And Daniel is to be brought up as one of the People?” he confirmed.

I nodded. “He is one already,” I said. “I had him circumcised. You must instruct him, and when he is older he will learn from my father’s Hebrew Bible.”

He drew a breath. “Hannah, in all my dreams, I did not dream of this.”

I pressed against his side. “Daniel, I did not know what I wanted when I was a girl. And then I was a fool in every sense of the word. And now that I am a woman grown, I know that I love you and I want this son of yours, and our other children who will come. I have seen a woman break her heart for love: my Queen Mary. I have seen another break her soul to avoid it: my Princess Elizabeth. I don’t want to be Mary or Elizabeth, I want to be me: Hannah Carpenter.”

“And we shall live somewhere that we can follow our beliefs without danger,” he insisted.

“Yes,” I said, “in the England that Elizabeth will make.”

Author’s Note

The characters of Hannah and her family are invented, but there were Jewish families concealing their faith in London as elsewhere in Europe, throughout this period. I am indebted to Cecil Roth’s moving history and to the broadcaster and filmmaker Naomi Gryn for giving me a small insight into these courageous lives. Most of the other characters in this novel are real, created by me in this fiction to match the historical record as I understand it. Below is a list of some of my sources, and for the history of Calais I am also indebted to the French historian Georges Fauquet who was generous with his time and his knowledge.

Billington, Sandra. A Social History of the Fool. London: Macmillan, 1984.

Braggard, Philippe, Johan Termote, and John Williams, editors. Walking the Walls, Historic Town Defences in Kent, C &frac;te d’Opale and West Flanders. Kent, UK: Kent County Council, 1999.

Brigden, Susan. New Worlds, Lost Worlds: The Rule of the Tudors 1485-1603. London: Allen Lane, 2000.

Cressy, David. Birth, Marriage and Death: Ritual, Religions and the Lifecycle in Tudor and Stuart England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Darby, H.C. A New Historical Geography of England before 1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Doran, John. A History of Court Fools. London: Richard Bentley, 1858.

Fontaine, Raymond. Calais, ville d’histoire et de tourisme. Broché: Syndicat d’initiative de France, 2002.

Green, Dominic. The Double Life of Doctor Lopez: Spies, Shakespeare and the Plot to Poison Elizabeth I. London: Century, 2003.

Guy, John. Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Haynes, Alan. Sex in Elizabethan England. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1997.

Hibbert, Christopher. The Virgin Queen: Elizabeth I, Genius of the Golden Age. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1991.

Loades, David. The Tudor Court. London: B. T. Batsford, 1986.

Marshall, Peter. The Philosopher’s Stone: A Quest for the Secrets of Alchemy. London: Macmillan, 2001.

Neale, J. E. Queen Elizabeth. London: Jonathan Cape, 1934.

Plowden, Alison. Marriage with My Kingdom: The Courtships of Elizabeth I. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1999.

– – -. The Young Elizabeth: The First Twenty-five Years of Elizabeth I. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1999.

– – -. Tudor Women: Queens and Commoners. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1998.

Ridley, Jasper. Elizabeth I. London: Constable, 1987.

Roth, Cecil. A History of the Marranos. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1932.

Somerset, Anne. Elizabeth I. London: Orion, 1997.

Starkey, David. Elizabeth . London: Vintage, 2001.

Turner, Robert. Elizabethan Magic: The Art and the Magus. Boston: Element Books, 1989.

Weir, Alison. Children of England. London: Pimlico, 1997.

– – -. Elizabeth the Queen. London: Pimlico, 1999.

Welsford, Enid. The Fool: His Social and Literary History. London: Faber and Faber, 1935.

Woolley, Benjamin. The Queen’s Conjuror: The Science and Magic of Doctor Dee. London: HarperCollins, 2001.

Yates, Frances. The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979.

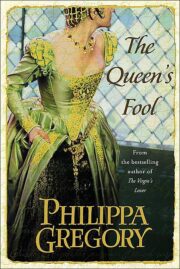

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.