There was no joy at the court in Whitehall, and the city, which had once marched out for Mary, now hated her. The pall of smoke from the burnings at Smithfield poisoned the air for half a mile in every direction; in truth it poisoned the air for all of England.

She did not relent. She knew with absolute certainty that those men and women who would not accept the holy sacraments of the church were doomed to burn in hell. Torture on earth was nothing compared with the pains they would suffer hereafter. And so anything that might persuade their families, their friends, the mutinous crowds who gathered at Smithfield and jeered the executioners and cursed the priests, was worth doing. There were souls to be saved despite themselves and Mary would be a good mother to her people. She would save them despite themselves. She would not listen to those who begged her to forgive rather than punish. She would not even listen to Bishop Bonner who said that he feared for the safety of the city and wanted to burn the heretics early in the morning before many people were about. She said that whatever the risk to her and to her rule, God’s will must be done and be seen to be done. They must burn and they must be seen to burn. She said that pain was the lot of man and woman and was there any man who would dare to come to her, and ask her to let her people avoid the pain of sin?

Autumn 1558

In September we moved to Hampton Court in the hopes that the fresh air would clear the queen’s breathing, which was hoarse and sore. The doctors offered her a mixture of oils and drinks but nothing seemed to do her any good. She was reluctant to see them, and often refused to take her medicine. I thought she was remembering how her little brother had been all but poisoned by the physicians who tried one thing and then another, and then another; but then I realized that she could not be troubled with physic, she no longer cared for anything, not even her health.

I rode to Hampton Court with Danny in a pillion saddle behind me for the first time. He was old enough and strong enough to ride astride and to hold tightly on to my waist for the short journey. He was still mute, but the wound had healed up, and he was as peaceful and as smiling as he had always been. I could tell by the tight grip on my waist that he was excited at the journey and at riding properly for the first time. The horse was gentle and steady and we ambled along beside the queen’s litter down the damp dirty lanes between the fields where they were trying to harvest the wet rye crop.

Danny looked around him, never missing a moment of this, his first proper ride. He waved at the people in the field, he waved at the villagers who stood at their doorways to watch as we went by. I thought it spoke volumes for the state of the country that a woman would not wave in reply to a little boy, since he was riding in the queen’s train. The country, like the town, had turned against Mary and would not forgive her.

She rode with the curtains of the litter drawn, in rocking darkness, and when we got to Hampton Court she went straight to her rooms and had the shutters closed so that she was plunged into dusk.

Danny and I rode into the stable yard, and a groom lifted me down from the saddle. I turned and reached up for Danny. For a moment I thought he would cling and insist on staying on horseback.

“Do you want to pat the horse?” I tempted him.

His face lit up at once and he reached out his little arms for me and came tumbling down. I held him to the horse’s neck and let him pat the warm sweet-smelling skin. The horse, a handsome big-boned bay, turned its head to look at him. Danny, very little, and horse, very big, stared quite transfixed by each other, and then Danny gave a deep sigh of pleasure and said: “Good.”

It was so natural and easy that for a moment I did not realize he had spoken; and when I did realize, I hardly dared to take a breath in case I prevented him speaking again.

“He was a good horse, wasn’t he?” I said with affected nonchalance. “Shall we ride him again tomorrow?”

Danny looked from the horse to me. “Yes,” he said decidedly.

I held him close to me and kissed his silky head. “We’ll do that then,” I said gently. “And we’ll let him go to bed now.”

My legs were weak beneath me as we walked from the stable yard, Danny at my side, his little hand reaching up to hold mine. I could feel myself smiling, though tears were running down my cheeks. Danny would speak, Danny would grow up as a normal child. I had saved him from death in Calais, and I had brought him to life in England. I had justified the trust of his mother, and perhaps one day I would be able to tell his father that I had kept his son safe for love of him, and for love of the child. It seemed wonderful to me that his first word should be: “good.” Perhaps it was a foreseeing. Perhaps life would be good for my son Danny.

For a little while the queen seemed better, away from the city. She walked by the river with me in the mornings or in the evenings; she could not tolerate the brightness of midday. But Hampton Court was filled with ghosts. It was on these paths and in these gardens where she had walked with Philip when they were newly married and Cardinal Pole newly come from Rome and the whole of Christendom stretched before them. It was here that she had whispered to him that she was with child, and gone into her first confinement, certain of her happiness, confident of having a son. And it was here that she came out from her confinement, childless and ill, and saw Elizabeth growing in beauty and exulting in her triumph, another step closer to the throne.

“I feel no better here at all,” she said to me one day as Jane Dormer and I came in to say goodnight. She had gone to bed early again, almost doubled-up with pain from the ache in her belly and feverishly hot. “We will go to St. James’s Palace next week. We will spend Christmas there. The king likes St. James’s.”

Jane Dormer and I exchanged one silent glance. We did not think that King Philip would come home to his wife for Christmas when he had not come home when she had lost their child, when he had not come home when she wrote to him that she was so sick that she did not see how to bear to live.

As we had feared it was a depleted court at St. James’s Palace. My Lord Robert had bigger and better rooms not because his star was rising, but simply because there were fewer men at court. I saw him at dinner on some days but generally he was at Hatfield, where the princess kept a merry circle about her and a constant stream of visitors flocked to her door.

They were not always playing games at the old palace either. They were planning how the country would be ruled by the princess when she came to her throne. And if I knew Elizabeth, and my Lord Robert, they would be wondering how soon it might be.

Lord Robert saw me only rarely; but he had not forgotten me. He came looking for me, one day in September. “I have done you a great favor, I think,” he said with his charming smile. “Are you still in love with your husband, Mrs. Carpenter? Or shall we abandon him in Calais?”

“You have news of him?” I asked. I put my hand down and felt Danny’s hand creep into my own.

“I might have,” he said provocatively. “But you have not answered my question. Do you want him home in England, or shall we forget all about him?”

“I cannot jest about this, and especially not before his son,” I said. “I want him home, my lord. Please tell me, do you have news of him?”

“His name is on this list.” He flicked the paper at me. “Soldiers to be ransomed, townspeople who are to be returned to England. The whole of the English Pale outside Calais is to come home. If the queen can find some money in the Treasury we can get them all back where they belong.”

I could feel my heart thudding. “There is no money in the Treasury,” I said. “The country is all but ruined.”

He shrugged. “There is money to keep the fleet waiting to escort the king home. There is money for his adventures abroad. Mention it to her as she dresses for dinner tonight, and I will speak with her after dinner.”

I waited until the queen had dragged herself up from her bed and was seated before her mirror, her maid behind her brushing her hair. Jane Dormer, who was usually such a fierce guardian of the queen’s privacy, had taken the fever herself, and was lying down. It was just the queen and I and some unimportant girl from the Norfolk family.

“Your Grace,” I said simply. “I have had news of my husband.”

She turned her dull gaze on me. “I had forgotten you are married. Is he alive?”

“Yes,” I said. “He is among the English men and women hoping to be ransomed out of Calais.”

She was only slightly more interested. “Who is arranging this?”

“Lord Robert. His men have been held captive too.”

The queen sighed and turned her head away. “Are they asking very much?”

“I don’t know,” I said frankly.

“I will speak with Lord Robert,” she said, as if she were very weary. “I will do what I can for you and your husband, Hannah.”

I knelt before her. “Thank you, Your Grace.”

When I looked up I saw that she was exhausted. “I wish I could bring my husband home so easily,” she said. “But I don’t believe he will ever come home to me again.”

The queen was too ill to transact the business herself, the fever was always worse after dinner and she could barely breathe for coughing; but she scrawled an assent on a bill on the Treasury for money and Lord Robert assured me that the business would go through. We met in the stable yard, he was riding to Hatfield and in a hurry to be off.

“Will he come to you here at court?” he asked casually.

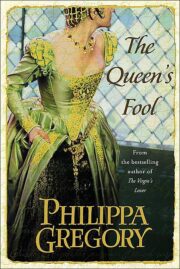

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.