It was natural that William’s mind should be on the great project which lay ahead and I was grateful that he had kept his promise to come back and see me.

Later that day I set out for The Hague, and in spite of the weather the people came out to cheer me as I rode along.

There I spent the next days waiting for news. When it came I could scarcely believe it to be true.

William had arrived safely and landed at Torbay. It was the fifth of November, an important anniversary — that of our wedding. I wondered if William remembered, but I expected his mind would be too engrossed in other matters. There was another anniversary to be remembered on that day. At home we had always celebrated the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot. Significant dates, and this would be another.

There were none to prevent William’s landing. He was welcomed by the Courtneys, one of the most important families in Devon, and given lodgings at their mansion.

Nothing happened for a few days and I was afraid that we might have been lulled into a sense of security and that the English army might suddenly appear.

It was never quite clear to me what happened at that time. Everything was so uncertain. There were many who deserted my father. He had been a great commander when he was young. He might have been so again. But I could imagine how disheartened he must have been, how saddened by the defection of those whom he thought were his friends.

I believe what would have hurt him most was Anne’s siding with his enemies. It hurt me, though I had done the same. But I was married to William. Need Anne have been so cruel?

Churchill deserted and came to join William and Anne left London with Sarah Churchill.

So his two daughters, whom he had loved dearly, had deserted him when he most needed their support.

HOW MUCH MORE DISTURBING IT IS to be away from the scene of action, desperately wondering what is happening, than to be in the midst of it. The imaginary disasters are often more alarming than the actuality. Reports were coming from England. The Dutch fleet had been wrecked, the Dutch army defeated, the Prince of Orange was a prisoner in the Tower. The Dutch had been victorious. The Prince had slain the King. Which was true? I asked myself. How could I know?

The strain was almost unbearable.

Constantly I thought of my father. What was he doing? How was he feeling? And William? What if those two came face to face?

When I prayed for William’s success, I could see my father’s reproachful eyes.

“Please God,” I prayed, “watch over him. Let him get quietly away where he can be safe and devote himself to his faith.”

At this time Anne Bentinck became very ill. She had been ailing for some time but now her malady had taken a turn for the worse.

Much as I distrusted the Villiers family, I had formed a friendship with Anne. I knew that she was her sister’s confidante and that, since she had married Bentinck, she had enjoyed a closer relationship with William. That was inevitable, for William had used Bentinck’s apartments as though they were his own and Bentinck was more often with William than with his own family. I liked Anne and although I could not altogether trust a Villiers I did respect her, and was very sorry to see her so ill.

When I went to see her I was horrified by the change in her.

The doctors had visited her, she told me.

“They will soon make you well,” I said.

Anne shook her head slowly. “No, Your Highness, I think this is the end.”

I was astounded. Anne was young. She had her life before her. The Bentinck marriage had been a happy one. It shocked me to hear her talk of dying.

“You are feeling sad. This is a sad time for all of us.”

“It is indeed. I wonder what is happening. I wish we could have some news.”

“You shall hear it as soon as it comes,” I promised her, and she thanked me.

I stayed with her for a while. To be with people gave me a respite from my continual imaginings of what was happening. I said I would call on her again and I added prayers for her recovery to those I said every day.

There was still no news. I heard that Anne’s condition had worsened and went again to see her.

She looked pleased and grateful for my coming.

“It will not be long now,” she said, and I had to put my ear close to her lips to hear her.

“My lady ... we ... we have not always been to you as we should. You have been a good mistress to us. My sister and I . . .”

“Do not fret,” I said. “The doctors will be here soon. They will do something.”

She shook her head. “No ... Forgive . . .”

“There is nothing for which I have to forgive you,” I said.

“Yes,” she answered. “My husband is with the Prince ... always with the Prince . . .”

“It was a great friendship between them. Your husband would have given his life for him. The Prince never forgets that.”

She smiled. “The Prince must be served.”

“There is great friendship between them.”

“The Prince demands much from those who love him. My husband ... he is like a slave to his master. He has little time for aught else. He is only allowed his freedom when the Prince is otherwise engaged. He is always expected to be there ... on the spot. It is the way of the Prince.”

This long speech seemed to have exhausted her and she was silent for a while.

Then she went on: “My lady ... my children ... when I am gone ... you will look to them.”

I said I would.

“They are young yet. If you could . . .”

“I will see that all is well,” I assured her. “You should not worry. Your husband will care for them. He is a good man. Anne, you were lucky . . .”

She nodded, smiling.

“Your promise,” she said. “Your forgiveness . . .”

“I give my promise,” I told her, “and forgive whatever there is to forgive.”

She smiled and her lips moved, but I could hear nothing.

I stayed with her, thinking of the day I had left England, a poor frightened child, in the company of the Villiers whom I did not much like.

There was not much time left for Anne. I was at her bedside with Lady Inchiquin and Madame Puisars and Elizabeth Villiers when she passed away.

We sat on either side of the bed, my husband’s mistress and I. Elizabeth was deeply affected by Anne’s death. They had been closer than any of the others and I was sure that they had shared confidences about Elizabeth’s relationship with William.

Was that what Anne had meant when she had asked for forgiveness? Death is a very solemn state. I could not feel the same anger in the presence of my rival on this occasion as I should on any other. She was suffering the loss of her beloved sister and I could only feel sorrow for her.

IT WAS STILL DIFFICULT TO GET NEWS. So far I understood that there had been no fighting and I was thankful for that; but I could not understand why this should be, grateful as I was for it.

My father’s first thoughts had been for his family. Mary Beatrice and the baby had been sent away to safety. I heard they were in France. Anne was still in hiding with Sarah Churchill.

Thoughts of my father filled my mind but all the time I reminded myself that he had brought this on himself and but for him it need never have happened.

If my uncle Charles could see what was happening he would smile that sardonic smile of his and say “I was right. It happened as I said it would. Poor foolish sentimental James. This is no way to rule a country, brother.”

It was heartbreaking. Sometimes I thought it was more than I could bear.

Before December was out I heard that my father was in France. Deserted by his friends, his army depleted, there had been no alternative. But for one thing I was thankful. There had been little loss of life and scarcely any bloodshed.

And then ... William was at St. James’s. It seemed that the enterprise, so long talked of, planned with such care, undertaken with such trepidation, was over and more successful than we had hoped in our most optimistic dreams.

Dispatches came from William. They were not brought to me and I was bitterly hurt. There was no word to me personally from William. No tender display of affection. After our last meeting, I had told myself, there was a change in our relationship.

I understood later that he could not suppress his resentment of me. Although he had changed since Gilbert Burnet had told him that I would not stand in the way of his becoming king, now that he was in England, he heard the views of some of the ministers there and the question was raised again. I was the heiress to the throne, they pointed out, and because he was my husband, he was not king in his own right. So, the old resentment was back. William could not endure taking second place to a woman. That which he craved beyond all things, he was told, belonged to his wife and his power depended on her good will. So he sent official documents to Holland and no communication to me.

To understand is to forgive, they say. If one has tender feelings toward another, one makes excuses. I wished I had understood then. I need not have felt so wounded, but I told myself that what I had thought of as William’s tenderness for me was transient. He had been carried along by the poignancy of the occasion and the possibility that that meeting might be our last on earth.

I heard how William had made his entry into London and thousands had come out to see him. I could visualize their disappointment. I remembered when he had come to London on a previous occasion and how somber he had seemed beside the King and his friends. William would have no smiles for the people. He did not look like a king. The people were silent. There were no cheers for the dour-looking Dutchman. What had he to recommend him, except that he was a Protestant and the husband of their new Queen Mary? Where was Queen Mary? She should be the one who was riding the streets.

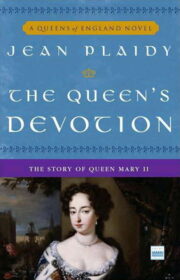

"The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" друзьям в соцсетях.