I think he was anxious to show himself closely allied to the Protestant cause, and since Monmouth was an avowed one, he wanted everyone to know that he was anxious to see a Protestant ruler on the throne of England, and even if the people chose the bastard Monmouth, he would accept him because of his religion.

So, there was William dancing — a little inelegantly it was true — but still dancing!

As for myself, I wanted to dance all the time. It reminded me of home and what evenings used to be like there. It was no wonder that Monmouth’s stay in Holland was like a dream to me for ever after.

Of course, it was Jemmy who made it so. He was so full of energy and fun. We used to walk in the gardens together. William was aware of this and made no protest, although previously I had never been able to see people without his approval. It was such a change and I was like a bird which has been caged too long and has just regained its freedom.

We laughed a great deal. There was always laughter where Jemmy was. We talked of the past. We promised that there should be more such visits. We must repeat these happy days.

The weather grew very cold. We were, after all, in the midst of winter. There was ice on the ponds.

“We must skate,” said Monmouth.

I had never skated before, I told him.

“Then I shall have to teach you how to skate. It is too good an opportunity to miss. It is so cold that the ice will be really hard and you need have no fear, for my arms will be ready to catch you. You will be perfectly safe with me.”

What fun it was as we slid along, with the skates buckled to my shoes and my petticoats caught up at the knees.

“One foot, then the other,” chanted Jemmy. And we laughed and laughed. I lost my balance and was caught in Jemmy’s arms.

We were watched by the people who joined in our mirth. I think they were all pleased to see me enjoying life. It was long since I had been so carefree and happy; and I did not have to feel guilty, for I had William’s consent to abandon myself to the fun of the moment.

There was one unpleasant incident, however.

It was carnival time, I heard. I did not know there were such festivities in Holland. I supposed that it would have taken place and I heard nothing about it but for Jemmy’s presence.

I believe that on every lake and pond in Holland people in fancy dress and masked took their sledges onto the ice.

William had said that he and I must ride together. Jemmy was, of course, very much in evidence with us.

It was so unusual to see William taking part in such frivolity, but he drove the sledge and with me beside him we skirted over the ice.

The pond was fairly crowded and as we swept along, right in our path, a sledge was coming toward us. In this, masked but obviously himself, was the Envoy Chudleigh. He came along directly before us and, as he must have been aware of our identity, we expected him to draw to one side to allow us to pass. Chudleigh, however, did no such thing, and we were obliged to draw to one side to let him go by.

I saw William’s lips tighten, and I heard him whisper under his breath: “I shall endure no more of this insolence. I shall have him recalled.”

His anger had not abated when we returned and he immediately sent a letter to England and asked that Chudleigh should return to England.

Chudleigh was not a man meekly to take blame for what he considered to have been correct behavior. He wrote to England. I heard afterward that he had explained how he had acted as only a man of breeding could act on such an occasion. He had had the right of way and, presuming the Prince and Princess of Orange did not wish to be recognized, as they were masked, he had not done so. He added that, at the court of The Hague, special privileges were given to those English who were ready to work against their own country and continual complaints were made against those who were loyal to it.

In spite of his protests, Chudleigh was recalled to London and soon after that Bevil Skelton came out as an envoy. I think that, in due course, William certainly wished the change had not taken place and it would have been more convenient for him had he retained Chudleigh.

I SHALL NEVER FORGET that February day when the news came to The Hague. Jemmy and I, enjoying the days, had no idea that it was all going to end so soon and in such a way.

I had so enjoyed this pleasant interlude and had refused to remind myself that it could not go on forever; but I had not expected there would be such an abrupt ending.

There came a message from William. I was to go to him at once for he had news which he wished to impart. In accordance with my usual custom, I obeyed immediately, and as soon as I stood before him I knew by the pulse I saw beating in his forehead and his suppressed excitement that the news for which he had been waiting had come at last.

He said: “King Charles is dead. He died a few days ago. It has taken some time for the news to reach us. He suffered a seizure on the first of the month and it was thought that he might recover, but this is indeed the end.”

I felt stunned. We had been waiting for it, but when it came it was a tremendous shock. I should never see again that kind uncle who had always had a smile for me, and I was overcome with sorrow, for with my grief came the realization that now the real trouble must start. My father, William, Jemmy; this meant so much to them all and they were all seeking the same goal.

I wanted nothing so much then as to be alone.

William sounded grim. He said: “Well, there is a new king of England now. They have accepted your father as James II.”

I could see his lips were twitching. He had never believed it could be so. They had forgotten James was a Catholic, and because he was next in line they had taken him as their king. It had been a simple passing of the crown from one king to another.

But all I could think of was that kind uncle who was dead and gone forever.

I SAT ALONE in my bedchamber. I had not prepared for bed. I knew I should not sleep. My thoughts were at Whitehall, and how I wished I were there.

What would happen now? I asked myself. My father was King. I felt we were on the edge of great events and I was filled with fear.

There was a light tap on my door and Anne Trelawny came in. She said: “The Duke of Monmouth is here. He says he must speak with you.”

“So late . . .” I said in alarm.

“He says it will not wait.”

I went through into an ante chamber and there was Jemmy, dressed for a journey, looking distraught and very sad.

He took my hands and, drawing me to him, kissed me.

“Mary, my dear, dear Mary, I am leaving.”

“Not tonight?”

He nodded. “I have been with William for the last hour or so. He says I must go. I cannot stay here. It was different when my father was there. He loved me, Mary, and I cannot tell you how much I loved him. And now he is gone ... and there is no one . . .”

“What are you going to do, Jemmy? Where are you going?”

“Away from here. William has given me money. He says he cannot offend the new King by harboring me here.”

“It is all so sad,” I said.

“Your father is the King now, Mary. I know that he loves you well. If you could plead with him to let me return ... write to him ... tell him I am innocent . . .”

“I will see what I can do. It is not quite the same between us as it used to be. There are differences in religion. That seems to sow so much discord. Jemmy, what is going to happen to you?”

“I do not know. I cannot say. If my father had only lived. While he was there I always knew I had a friend.”

“I am your friend, Jemmy.”

“I know it. I know it well. That is why I ask you this. When the time comes ... you will plead for me?”

I nodded.

“Not yet. It is too soon. He will have other matters with which to concern himself. But you will do this for me?”

“I will,” I said. “I will. But Jemmy, you cannot go tonight.”

“I must. William has said I must. But I had to say good-bye to you. I shall let you know what is happening to me, and you will do that for me ... plead with your father to allow me to come home.”

“I will do that, Jemmy.”

“Dear Mary, dear little cousin.”

“God bless you, Jemmy. I shall pray for you.”

We embraced and he was gone.

THERE WERE LETTERS FROM MY FATHER — one was for me, telling me of his accession and the last hours of the late King. He had been with him at the end. My father then went on to express his undying affection for me. It was a most tender and moving letter. William received a formal announcement of the accession.

William read the letter which my father had written to me and kept it. I was amazed when he read it to the Assembly, as though it had been addressed to him.

He was evidently accepting the accession of my father, now that it had happened, without opposition and intended it to be thought that it had never occurred to him that it would be otherwise.

Strangely enough, he showed me the letter he wrote in return. He must have realized that during those weeks when I emerged from my solitude and mingled with the members of the court and Jemmy, I had learned something of his hopes and schemes.

It seemed now as if he wished me to believe that he rejoiced in my father’s accession.

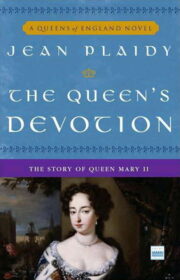

"The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" друзьям в соцсетях.