I looked forward to it with enthusiasm and felt almost happy.

I wrote to my sister Anne, to Mary Beatrice and to Frances Apsley to tell them my news. I had not let Frances know how unhappy I had been; I never allowed myself to criticize William in any way. Now I did not have to pretend so much, for I was no longer miserable.

We had a great deal of fun preparing for our journey. Elizabeth Villiers acted a little strangely. She said she wanted to see me. It was very shortly before we were due to leave.

“I want to ask Your Highness’s permission to remain behind,” she said. “I have a certain weakness of the throat which I know would be aggravated by the damp air and I am afraid I should be ill if I spent much time on the waterways. I have been advised in this.”

I was surprised. I had always thought she was particularly healthy, but I did not protest. I was never fond of her company and felt no great need for it — only a mild pleasure that I should be deprived of it.

That was a very pleasant journey. I was greeted everywhere I went by those kind and homely people. I was impressed by the cleanliness of their dwellings, the manner in which they conveyed their pleasure in seeing me, which seemed very sincere, so that I felt they really were glad to welcome me, for they would not have pretended to be glad if they were not.

There was less ceremony than at home in England. People would come and take my hand; they would bring forward their children for me to admire. I was really happy during those days. There was something peaceful about the flat green land, and when the children brought me flowers which they had picked from the fields, I was reminded that soon I should have a child of my own. Yes, for the first time since coming to Holland, I was truly happy.

The night air was indeed damp and one day, to my dismay, I awoke shivering intermittently. I tried to shake this off, but it persisted. In a day or so I had a fever.

Doctors were called. They said I was suffering from the ague. It was a change of climate, though the air around The Hague Palace was noted for its dampness.

Thus my progress through the country did not end as happily as it had begun. I was taken back to the House in the Woods.

Elizabeth Villiers was there. She looked taken aback when she saw me and, I fancied, disappointed.

“Your Highness is ill?” she said with a pretence of concern.

“It is the dampness of the air, they say,” said Anne Trelawny. “Her Highness is to go immediately to bed.”

Elizabeth continued to look displeased. I did not trust her. She made me feel slightly uneasy.

I began to feel very ill and then ... it started.

The pains were violent. I did not know what was happening to me. I lost consciousness for a while and when I regained it I found several doctors at my bedside.

It was morning — that very sad morning — when they came to tell me I had lost my child.

I had never been so miserable in my life.

William came. He looked very angry. The child of our hopes was not to be.

“What did you do?” he demanded.

“Nothing ... nothing ... it just happened,” I stammered.

He looked at me with scorn. He was so disappointed and angry. Then he left me. It was almost as though he could not trust himself not to do me some harm if he stayed.

I felt a resentment then. I had wanted the child as much as he had. Why did I not tell him that? Why did I allow myself to be treated so? He frightened me. When he was not there I planned what I would say to him, but when he came my courage failed me.

I thought of Mary Beatrice who had only little Isabella left of all her children, and how she had lost the little Prince whose coming had so disappointed William and who, had he lived, would have ruined William’s hopes of the throne, and I thought: am I to be cursed in the same way?

Anne Trelawny tried to persuade me not to despair because it was only the first. That did not help me. I had lost my child. I turned my face to the pillow and wept.

WILLIAM, INSPIRED BY NEW HOPES that there was no impediment to my inheritance, was determined to get his heir, and as soon as my health began to improve his visits continued, and it was not long before I was pregnant again.

One day there was a letter from England. It was addressed to William and it evidently annoyed him to such an extent that he could not help showing the bitterness of his feelings.

It was from my father. The relationship between them had never been cordial. They could not help seeing each other first as Catholic and Protestant. I could sympathize with William in this when I heard how his country had suffered under the Spanish yoke and how the terrible Inquisition had inflicted such extreme torture on the people of Holland. I had heard that some thirty thousand of them had been buried up to their necks and left to die unless they accepted the Catholic faith as the true one. William saw my father as a man who would spread this kind of terror throughout the world.

As for my father, he recalled Cromwell and his Puritans who had murdered his father.

They were born to be enemies. They were so different in every way — my father warm and loving, William cold and austere. How strange that the two most important men in my life should be so different and how sad that they should have been such enemies.

And now here was another cause for enmity.

William said to me coldly: “I have had an accusation from your father that I do not take good care of you.”

“Oh no,” I said.

“But yes. He thinks that it was strange that you should suffer from the ague which you never did under his care. He informs me that the Duchess, his wife, and your sister, the Lady Anne, wish to visit you.”

I could feel nothing but joy. I clasped my hands and could not help exclaiming: “Oh, how happy that will make me.”

“They propose to come, as your father says, incognito. ‘Very incognito’ are his words. They have already sent a certain Robert White on ahead to procure a lodging for them near the palace so that there will be nothing official about the visit.”

“Why do they want to come in this way?”

He looked at me oddly. “They seem to think you are not being well treated here. Perhaps you have given some intimation of this?”

“Why? What do you mean?”

He lifted his shoulders. “The good ladies are to assure themselves — and your father — that you are being treated according to your rank. It would seem they have been led to believe this is not so.”

He was spoiling my pleasure in the anticipation of their arrival.

I said quickly: “You would not . . .”

“Refuse to allow them to come? I could scarcely do that. Rest assured, the lady spies will be well received when they arrive, though they will be ‘very incognito.’ ”

Nothing could really spoil my delight and I joyously awaited their arrival.

AND WHAT A JOY IT WAS TO SEE THEM. There was my dear, dear sister, who had been so ill when I left, now in radiant health.

It was wonderful to see me, she told me.

“When you went away, I wept for days. Sarah thought I should do myself some harm with my sorrow. Dear, dear Mary, and how do you like it here?”

She looked around the chamber. It was attractive, she said, but not like dear St. James’s and Richmond.

She was talking a great deal — for Anne — but this reunion was a very special occasion and even she was moved out of her usual placidity.

Then there was my stepmother. I saw the change in her. Grief had left its mark on her.

I did not mention the recent death of her baby son, but she knew I was thinking of it.

There was so much to talk of. I wanted news of my father.

“He never ceases to talk of you,” Mary Beatrice told me. “He wishes you were back with us and reproaches himself for letting you go.”

“It was no fault of his. He would have kept me in England if he could.”

She nodded. “He could do nothing,” she said. “But he still blames himself. This appears to be a pleasant country. The people are very agreeable.”

“Orange,” said Anne. “It’s a strange name for a country.”

“I call you Lemon ... my dear little Lemon,” said Mary Beatrice. “Orange and Lemon, you see. Do I not, Anne?”

“Yes,” said Anne. “She says, ‘I wonder how little Lemon is today among all the Oranges.’ ”

We were all laughing. There was so much to know. How were all my friends — the Duke of Monmouth, for instance. All missing me, I was told.

I said: “It is wonderful that you have come.”

“Your father was so uneasy about you. He would have liked to come himself but he could hardly have done that. It would have made it too official. But when we heard what was happening here . . .”

“What did you hear?”

Mary Beatrice looked at Anne who said: “People wrote home ... some of the ladies, you know. They wrote that the Prince does not treat you well. Does he not?”

I hesitated — and that was enough.

“Lady Selbourne wrote home and said that you were neglected by the Prince who treated you without respect.”

“The Prince is very busy,” I said quickly. “He is much occupied with affairs of state.”

“He will always be Caliban to me,” said Anne. “That was Sarah’s name for him.”

I said: “Pray, do not let anyone hear you say that.”

“Well,” laughed Anne. “He is rather alarming. My poor Mary, I am sorry for you. I can’t help being glad he is not my husband.”

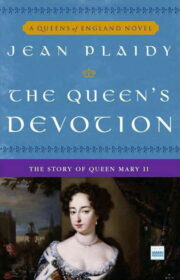

"The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" друзьям в соцсетях.