I was sure then that Lady Frances was watching us closely, for that letter fell into her hands.

I was horrified when she came to my closet and said that she wanted to talk to me. She was very respectful, as always, but her mouth was set in stern lines and I saw that she was determined to do what she considered her duty.

She said: “You have been corresponding with Mistress Apsley.” She held up the letter which I had given to the footman. She must have ordered him to give it to her.

“You ... have read it?” I gasped.

“Lady Mary, your father has put me in charge of this household. It is therefore my duty to know what goes on in it.”

I was trying to think what I had written in that letter. I was always in a state of high emotion while I wrote them, words flowed out and I was never sure half an hour afterward what I had said except that all the letters contained pledges of my constant love.

Then I remembered that I had mentioned something about the scandal concerning the Duke of Monmouth and Eleanor Needham and that the Duchess of Monmouth had taken the matter mightily to heart.

That had been indiscreet, of course, and I should not have referred to it. Nor should I, if I had thought anyone was going to read it other than Frances. I was rather proud of my eloquence and I remembered the end. “I love you with a love that never was known by man. I have for you more excess of friendship than any woman can for woman and more love than even the most constant husband had for his wife, more than can be expressed by your ever obedient wife and humble servant who wishes to kiss the ground where you walk, to be your dog on a string, your fish in a net, your bird in a cage, your humble trout. Mary Clorine.”

I had been so proud of those words when I wrote them; now I blushed to remember them.

Lady Frances was looking at me very strangely. I noticed an uncertainty in her eyes. I had realized that she was not sure how to act.

She began: “His Grace, your father . . .” Then she shook her head; her lips moved as though she were talking to herself.

“It is a very excessive friendship,” she said at length. “I think it would be better if we did not speak of it. And the Lady Anne ... ?”

“My sister writes to Mistress Apsley because I do,” I said.

“I must ponder this matter,” she said, as though to herself.

“I do not understand. Is it not good to have friends ... to love?”

“Perhaps it would be well if you did not meet for a while.”

“Not meet?”

“And not ... write such letters.”

“I do not understand . . .”

“No,” said Lady Frances briskly. “I am sure you do not.”

“Not to see her . . .” I murmured blankly.

“I think you might meet, say on Sundays. You will be in the company of others then. And perhaps on Holy Days.”

I stared at her in dismay. I had been in the habit of taking any opportunity I could to be with Frances.

I said: “Lady Frances, you have my letter.”

She looked at me with caution in her eyes. I knew that she was eager not to displease me. It was a fact that my stepmother was pregnant, but who could be sure what the result of the pregnancy would be? And if the situation did not change, Lady Frances might be at this moment earning the deep resentment of the future Queen of England.

“We will forget this matter,” she said slowly. “I think, my Lady Mary, it would be well if we were a little discreet.”

She was smiling at me. Gravely I took the letter from her and she left me.

IT WAS A BLEAK JANUARY DAY in the year of 1675. I would soon be thirteen years old. My father had been very disappointed because, instead of the hoped-for boy, Mary Beatrice had produced a girl. He tried not to show it and declared that he was very happy with our little sister.

I found Mary Beatrice in excellent spirits. She confided to me that she wanted the child to be baptized in the Catholic faith and she was afraid there would be some opposition to that.

“Your father desires it, too,” she said. “And I am going to be very bold. I shall command Father Gallis to baptize the baby before anyone else can do anything about it.”

In view of the conflict which was growing over this matter of the Catholic faith, I thought this was a very daring thing to do. I knew that my father was very sad because Anne and I were being brought up as Protestants, and he only accepted this because if he had attempted to stop it we should have been taken away from him altogether and he would probably have been sent away from court.

I was amazed that the usually meek Mary Beatrice could be so bold; but I was learning that people will do a great deal for their faith.

It was no use trying to dissuade her, and Father Gallis baptized little Catherine Laura. The name Catherine was given to the baby in honor of the Queen and she was Laura after Mary Beatrice’s mother.

Mary Beatrice had no qualms about what she had done. I supposed this was due to the fact that, whatever misdemeanor she committed at court was of no importance because she had done right in the sight of Heaven.

However, she did seem a little subdued when she told me, a few days later, that the King had announced his intention of coming to St. James’s to discuss the baptism with her.

I was horrified.

“The King will be angry,” I said. “You have been very bold. It is not that he will care very much. He is careless about such matters. But you have to remember that the people are not very pleased.”

She held her head high, but I could see that she was apprehensive. I begged her to tell me quickly what the King said when he came. I felt she had gone too far, even for his good humor.

She kept her word and I hastened to her. I found her a little baffled.

She said: “I told the King what I had done but it was not as I expected. He did not show anger at all. He just smiled in a rather absent way and talked of other things. I was overjoyed. My baby is a Catholic, even though she was born in this heretic land.”

“Do not be too sure of that,” I said. “There are people around us who could create mischief.”

The next day I was told that the baby was to be baptized in the Chapel Royal, according to the rites of the Church of England, of course, and one of the bishops would perform the ceremony.

I was astounded. Mary Beatrice had said the King had not seemed to hear what she had said.

“He did hear,” I assured her. “He is sweeping it aside, as he does anything that is unpleasant. He understands what you did. Most people would have been furious ... banished you to the Tower. But the King does not act like that, so he brushes it aside as though it has not happened. But he will have his way all the same and Catherine Laura will be baptized in the Church of England.”

“But she is a Catholic!” Mary Beatrice was almost in tears. She was bewildered. She did not understand the ways of our court. The King, so charming ... smiling, showing no signs of anger, had just swept aside her childish action. As far as he was concerned, it had never happened.

Soon after I heard that my sister Anne and I were to stand as sponsors and the Duke of Monmouth was to join us.

When it was over my father came to see me.

“The Duchess told you that there was a previous baptism,” he said.

“Yes,” I replied. “She did.”

He was frowning and staring before him. “The King has spoken to me very seriously,” he went on.

“The King behaved to the Duchess as though it were of no importance.”

“He understood her motive. ‘She is young,’ he said, ‘and quite ignorant of the significance of her action. She is not to be blamed, but watched that she commits no more such follies.’ If this were known, Gallis would be hanged and quartered. As for myself and the Duchess, he warned me that at least we should be sent away from court. No one must know that this ceremony took place. Please, never speak of it.”

I did understand. I was growing up fast. I saw that my father could be in danger.

I threw myself into his arms and clung to him.

“I promise, I promise,” I cried.

THE ORANGE MARRIAGE

Life had changed since we had been launched on the court. We were often in the company of the King. Both Anne and I looked forward to those occasions, for he treated us with great affection and lack of ceremony, as always the kindly uncle. How differently I see such relationships when I look back now!

In those days I thought all the affectionate words and actions meant he really cared for us. He did, of course, in his lighthearted way, but I know now what his main aim was. We were in his care. We were good little Protestants. We were in line to the throne and my uncle wanted the people to know that, although he himself could not provide them with a Protestant heir, he would make sure that, in spite of his brother’s love affair with the Catholic Church, those who followed him to the throne should be of the approved religion.

Although I know now how this matter was always there in our lives, I did not understand then how very important it was and how it would shape my life.

So we were now at court, and I must say we were finding the experience delightful. We were treated with the utmost respect wherever we went. Lady Frances was almost deferential at times. Elizabeth Villiers was wary, and so was Sarah Jennings. She and Anne were inseparable, in spite of Anne’s passion for Frances Apsley. It was Sarah who was Anne’s alter ego.

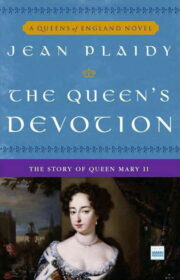

"The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Devotion: The Story of Queen Mary II" друзьям в соцсетях.