We looked up startled, for this was no ordinary visit. Six members of the Municipaux bad come into the room.

I rose to my feet.

“Messieurs,” I began.

One of them spoke, and his words struck me like the funeral knell for a loved one.

“We have come to take Louis-Charles Capet to his new prison.”

I gave a cry. I reached for my son. He ran to me, his eyes wide with terror.

“You cannot …”

“The Commune believes it is time he was put into the care of a tutor.

Citizen Simon will care for him. “

Simon! I knew this man. A cobbler of the lowest, coarsest, crudest type.

No, no, no! ” I cried.

We’re in a hurry,” said one of the men roughly.

“Come on, Capet.

You’re moving from here. “

I could feel my son clutching my skirts. But rough hands were on him;

they were dragging him away. I ran after them but they threw me off.

Elisabeth and my daughter caught me as I fell.

They had gone. They had taken my boy with them.

I could think of nothing but that. My sister-in-law and my daughter tried to comfort me.

There was no comfort. I shall never forget the cries of my son as they carried him away. I could hear him screaming for me.

“Maman … Maman … don’t let them.”

It haunts my dreams. Never never can I forget. Never never can I forgive them for doing this to me, This was the depth of sorrow; there could be nothing more terrible. I was wrong. These fiends had found they could plunge me into even further despair.

So I was without him.

Life had no meaning now. He was lost to me . my beloved son, my baby.

How could they do this to a woman? Was it because they knew that while I had him with me I could go on living, I could hope, I could even believe that there was some happiness left to me?

I lay on my bed. My daughter sat beside me holding my hand, as though to remind me that she still remained. How I could have lived through those days without her and Elisabeth I cannot imagine.

Madame Tison was acting strangely. Perhaps she had been doing so for some dme. I was scarcely aware of her. I could think only of my son in the hands of that brutal cobbler. What were they doing to him? Was he crying for me now? I almost wished that he had died as his brother had, rather than that he should have come to this pass.

Sometimes I heard as though from a long way off Madame Tison storming at her husband; sometimes I heard her giving way to wild crying.

And one day she came into my room and threw herself at my feet.

“Madame,” she cried, ‘forgive me. I am going mad because I have brought these troubles on you. I have spied on you . They are going to murder you as they murdered the King . and I am responsible. I see him at night . I see his head all bloody . it rolls off, Madame, on to my bed. I must have your pardon, Madame. I am going mad mad. “

I tried to calm her.

“You have done as you were bidden. Don’t blame yourself. I understand.”

“It’s dreams … dreams … nightmares. They won’t go…. They are after me … even by day. They won’t go. I murdered the King … I .

The guards rushed in and carried her away.

Madame Tison had gone mad.

From one of the window-slits on the spiral staircase I could see the courtyard where my son was sent out for fresh air.

What joy it seemed when I saw him after all those days.

He no longer looked like my son. His hair was unkempt;

his clothes were dirty and he wore the greasy red cap.

I did not call him, I feared it would distress him; but at least I could stand there and watch. Each day at the same hour he came there;

so here was something to live for. I should not speak to him, but I should see him.

He did not seem unhappy, for which I was grateful. Children are adaptable. Let me be grateful for that. I saw what they were doing.

They were making him one of them, teaching him crudities . making him a son of the revolution. This I realised was the duty of the tutor, to make him forget chat the blood of Kings ran in his veins, to rob him of dignity, to prove that there was no difference between the sons of Kings and the sons of the people. I shuddered as I heard his shouts. I listened to his singing. Should I not rejoice that he could sing?

“Allans enfants de la Patrie .. The song of the bloodthirsty revolution. Had he forgotten the men who had murdered his father? I listened to the voice I knew so well:

“Ah, (a ira, fa ira, a ira En de frit des aristocrats et de la plule, Nous nous mouillerons, mais fa fm ira Ca ira, a ira, fa ira.”

Oh, my son, I thought, they have taught you to betray us.

And I lived for these moments when I could stay at the slit in the wall and watch him at play.

It was only a few weeks after they had taken my son from me when at one o’clock in the morning I heard a knocking at the door.

The Commissaries had come to see me. The Convention had decreed that the Widow Capet was to stand trial. She would therefore be removed from the Temple to the Con-dergerie.

I knew that I had received my death sentence. They would try me as they had tried Louis.

There was to be no delay. I was to make ready to go at once.

They allowed me to say goodbye to my daughter and my sister-in-law.

I begged them not to weep for me and I turned away from their sad stunned looks.

“I am ready,” I said.

I felt almost eager, because I knew this meant death.

Down the stairs, past the slit in the window—no use to look out now.

Never . never to see him again. I faltered and struck my head against a stone archway. “Have you hurt yourself?” asked one of the guards, moved as sometimes these brutal men were by a flash of kindness.

“No,” I answered.

“Nothing can hurt me now.”

So I am here . the prisoner in the Conciergerie.

This is the grimmest of all the prisons in France. It has become known during this reign of Terror as the anteroom of death. I am waiting to be called in to death as so many waited to be called to see me in my state apartments of Versailles.

I know now that I am here that there are not many days left to me.

Strangely enough I found kindness here. Madame Richard was my jail or—a very different woman from Madame Tison. I saw her compassion from the first. Her first act of kindness was to tell her husband to fix a piece of carpet over the ceiling from which water dripped on to my bed. She told me that when she had whispered to the market woman that the chicken she was buying was for me she had surreptitiously picked out the most plump.

She implied in a hundred ways that I had my friends.

Madame Richard had a boy of the same age as the Dauphin.

“I do not bring Fanfan to see you, Madame,” she told me, ‘because I feared it might remind you of your son and make you sadder. “

But I said I would like to meet Fanfan and she brought him. It was true I wept over him, for his hair was as fair as the Dauphin’s, but I loved to listen to his talk and I looked forward to his visits.

My health was beginning to fail; the damp caused pains in my limbs and I suffered frequent haemorrhages. My room was small and bare; the walls were damp and the paper, stamped with the fleur-delis, was peeling off in many places. There was herring-bone pattern on the stone floor which I stared at so much that I knew every mark. The bed and the screen were the only furniture. I was glad of the screen, for I was under constant supervision and it afforded me the little privacy I had. There was a small barred window which looked on to the paved prison yard, for my room was-a semi-basement.

Madame Richard had given me the services of one of her servant girls, Rosalie Lamorliere, a kind and gentle creature like her mistress, and these two did everything they could to make my life more bearable.

It was Madame Richard who prevailed on Michonis, the chief inspector of the prison, to bring me news of Elisabeth and Marie Therese.

“What harm to the Republic could that do?” demanded the good woman.

And Michonis, who was a tender-hearted man, could see no harm either.

He even had clothes brought for me from the Temple and he told me that Madame Elisabeth had said they were what I should need. I was pleased, because in spite of my despair I had always been conscious of my appearance and more able to bear my misfortunes if I was suitably dressed. So it was with a mild pleasure that I discarded the long black dress which was frayed at the hem and the white fichu which never seemed white enough, for something which I thought more fitting.

My eyes were constantly watering. I had shed so many tears. I missed the little porcelain eye-bath I had used in the Temple, but Rosalie brought a mirror for me which she told me was a bargain. She had paid twenty-five sous for it on the quai. I felt I had never possessed such a charming mirror. It had a red border with little figures round it.

The length of the days t There is nothing I can do. I write a little but they are watchful and suspicious. There is always a guard sitting in the corner of my room. Sometimes there are two. I watch them playing cards. Madame Richard brought me books and I read a great deal. I have kept a little leather glove which my son used to wear when he was very small. It is one of my greatest treasures—in a locket I have a picture of Louis-Charles. I often kiss it when the guards are not looking.

The nights are so long. I am not allowed a lamp or even a candle. The changing of the guard always awakens me if I I am dozing. I sleep very little.

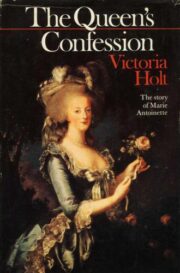

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.