We used to laugh at him. I did not realise then that while we were laughing together about his odd habits, he was deciding -my future, and but for him I should not be where I am at this moment. Caroline discovered that there was a possibility that either I she or I might marry the King of France, which set us I giggling at the incongruity of this, for he was an old man nearly sixty and we thought it would be funny to have a husband who was older than our mother. But when the

Dauphin of France—the son of that King who might have been a husband to one of us died and his son became Dauphin, there was great excitement because the new Dauphin was only a boy, about a year older than I was.

Sometimes Caroline and I talked about “The French Marriage and then we would forget about it for weeks; but all the time we were growing farther and farther away from childhood. Ferdinand tried seriously to discuss it with us how good it would be for Austria if there was an alliance between Hapsburg and Bourbon.

The widow of the recently dead Dauphin, who had great influence with the King, was against it and wanted a princess from her own House to marry her son; but she died suddenly of consumption, which she had probably caught when nursing her husband, and my mother was very pleased.

My brother Joseph’s poor unhappy wife died of the small pox, and my sister Maria Josepha, who was four years older than I, caught it and died. She was on the point of going to Naples to marry the King and our mother decided that an alliance with Naples was necessary so Caroline should be the bride instead.

This was the biggest tragedy of all so far. I had loved my father and had been sad, in my way, when he had died, but Caroline had been my constant companion and I could not imagine what it would be like without her. Caroline, who felt everything more deeply than I, was heartbroken.

I was twelve; Caroline was fifteen; and as Caroline had been selected for Naples, my mother at this time decided to train me to be ready to go to France. She announced that I should no longer be called Antonia.

I should be Antoinette or Marie Antoinette. That in itself made me seem like a different person. I was now brought into my mother’s salon and made to answer the questions important men put to me; I had to have the right answers and was primed beforehand, but it was so easy for me to forget.

The comfortable life was over. I was watched; I was talked about; and I fancied that my mother and her ministers were trying to represent me as a very different person from the one I was rather the person they wanted me to be, or the French would like me to be. I was always hearing stories about my goodness, my charm and cleverness which astonished I me. When I was younger, Mozart the musician had come to the Court; be was only a child then, but brilliant, and my mother was encouraging him. When he came into the great salon to play to the company he was so overawed that he slipped. and fell and everyone laughed. But I ran out to see if he was hurt and to tell him that it did not matter, and after that we became friends and he played for me specially. He said once that he would like to marry me, and as I thought that would be pleasant, I agreed to his proposal. This was I remembered and told about me. It was supposed to be one of the ‘charming’ stories. On one occasion my mother told me that the French Ambassador would probably talk to me when I visited her salon and if he were to ask me which nation I should most I like to rule I must say “The French’; and if he were to ask why, I was to reply: “Because they had Henri Quatre the Good and Louis Quatorze the Great.” I learned it off by heart and was afraid I should get it wrong because I was not very sure who these people were; but I managed it and that was another story which was told about me. I was supposed to learn about the French; I was to practise speaking French; everything was changing.

As for Caroline, she was always weeping and was no longer the pleasant companion she had been. She was very frightened of marriage and knew she was going to hate the King of Naples.

Our mother came to the schoolroom and talked to her very severely.

You are no longer a child she said, ‘and I have heard ( that you have been very bad-tempered. ” :

I wanted to explain that Caroline was only bad-tempered because she was frightened; but it was impossible to explain to my mother.

Then she looked at me and went on: “I am going to separate you from Antoinette. You spend your time in stupid chattering and there is to be no more of this useless gossip. It will stop at once. I warn you that you will be watched, and you, Caroline, as the elder, will be held responsible.”

Then my mother dismissed me and kept Caroline there to lecture her further on how she should behave.

I went away with a heavy heart. I should miss Caroline so much.

Strangely enough I did not think of my own fate. France was too far off to be real, and I had perfected my natural inclination to forget what it was not pleasant to remember.

Caroline left at last pale-faced, silent and not in the least like my gay little sister. Joseph accompanied her and I believe he was quite sorry for her; there was something good about Joseph although he was so haughty and pompous.

There was trouble with another of my sisters, but this seemed more remote, for Maria Amalia was nine years older than I was. Caroline and I had known for a long time that she was in love with a young man of the Court, Prince Zweibriicken, and hoped that she would be able to marry him, which was perhaps foolish of her, for she should have known that we had to marry Heads of States for the good of Austria. But Maria Amalia was like me in that she was apt to believe what she wanted to, so she went on believing that she would be allowed to marry Prince Zweibriicken.

Caroline’s fears were fully realised. She was very unhappy in Naples and wrote home that her husband was very ugly, but because she remembered what my mother had told her she tried to be brave, and added that she was growing quite accustomed to him. She wrote to Countess von Lerchenfeld, who helped Aja as governess:

“One suffers martyrdom, and it is all the greater because one must pretend to be happy. How I pity Antoinette who has to face this. I would rather die than suffer it again. But for my religion I should have killed myself rather than live as I did for eight days. It was like hell and I wished to die. When my little sister has to face this I shall weep for. her.”

The Countess had not wanted to show me this, but I begged and pleaded and she gave way as she always did; and when I read it I wished I hadn’t. Was it really so bad? My sister-in-law Isabella had talked about killing herself. I, who loved life so much, could not understand this attitude; yet it seemed strange that those two who had had so much more experience of life than I should both have talked like that.

I thought about Caroline’s letter for some hours and then it slipped to the back of my mind and I forgot it perhaps because my mother was now turning her attention more and more on me.

She came to the schoolroom to investigate my progress and was horrified when she realised how little I knew. My handwriting was untidy and laborious. As for speaking French, I was hopeless, although I could chatter in Italian; but I could not write even German really grammatically.

My mother was not angry with me; she was merely pained. She drew me to her, held me in the crook of her arm and explained to me about the great honour which might be done to me. It would be the most wonderful thing in the world if this plan which Prince von Kaunitz here in Vienna and the Due de Choiseui in France were trying to work out could come to fruition. It was the first time I had heard the Due de Choiseul’s name mentioned and I asked my mother who he was. She told me that he was a brilliant statesman, adviser to the King of France and, most important of all, A Friend to Austria. So much depended on him and we must do nothing to offend him. What he would say if he knew what a little ignoramus I was, she could not imagine. The whole plan would prob ably founder.

She looked at me so severely that I was momentarily down cast. It seemed such a great responsibility; then I felt my mouth turning up at the corners because I could not believe I was all that important. And as I laughed I saw that my mother was trying not to smile, so I put my arms about her neck and said I was sure Monsieur de Choiseui would not mind very much that I was not clever.

She held me tightly against her, and then, putting me from her, looked severe again. She told me about the mighty Sun King who had built

Versailles which, she said, was the greatest palace in the world, and die French Court was the moat cultured and elegant, and that I was the luckiest girl in the world to have a chance of going there. I listened for a while to her accounts of the wonderful gar dens and the beautiful salons which were far more splendid than anything we had in Vienna, but soon, although I was nodding and smiling, I was not really listening.

I suddenly realised that she was saying my governesses were not suitable and I must have other teachers. She wanted me, in a few months’ time, to be talking in French, thinking in French, so that it would be as though I were French.

“But never forget that you are a good German.”

I nodded, smiling.

But you must speak good French. Monsieur de Choiseui writes that the King of France has a very sensitive ear for the French language, and that you should have an accent of grace and purity which will not offend aim. You under stand? “

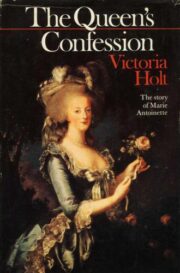

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.